I owe my financial independence to Jack Bogle and the firm he founded, the Vanguard Group. Most of my own equity and bonds are Vanguard funds; decades of compounding higher returns from lower fees gave me this financial independence.

But when I hear some investors refer to Vanguard and indexing as a religion, I say enough is enough! Religion generally calls for unquestioning faith and that’s where the analogy breaks apart for me. I question everything.

Though I can’t remember developing a financial plan that didn’t include at least some Vanguard funds and solutions, I also can’t remember ever doing one that was all Vanguard. I visited Vanguard headquarters outside of Valley Forge, Pa., late last year and met with Francis M. Kinniry, a principal in Vanguard’s Investment Strategy Group, and John Ameriks, head of the Vanguard Quantitative Equity Group. I asked about investments for which I use non-Vanguard solutions as well as products I’m less enthused about.

A willingness to discuss differing viewpoints is one way I judge the sincerity of a financial provider. Few financial powerhouses are willing to have such a conversation, especially on the record. Here’s a recap of our point-counterpoint discussion.

Point: I don’t use Vanguard money market accounts to stash cash.

Admittedly, yields have rocketed with the prime money market yield rising 40-fold to 0.4% annually. But I tend to recommend either bank money market accounts or high-yield savings accounts backed by the FDIC that pay up to 1.05%. That may not seem like much, but each $100,000 equates to $650 in additional annual interest. And the funds can easily and quickly be moved back to Vanguard via an ACH linked to a mutual fund or brokerage account. Higher return with less risk (more U.S. government insurance) is an easy call for me.

Counterpoint: Largely true, Kinniry said, but he noted that it takes time to do this; if an investor is willing to spend the time, she can make more with less risk. He added that there were long stretches when the prime money market was yielding as much as average bank money markets and savings accounts.

Point: I use bond funds sparingly.

I didn’t make some silly argument that bonds are better than bond funds because they have less interest rate risk. Roughly 70% of my own fixed income is in bank CDs opened directly with a bank. That’s because they yield more with less default risk and especially less interest rate risk.

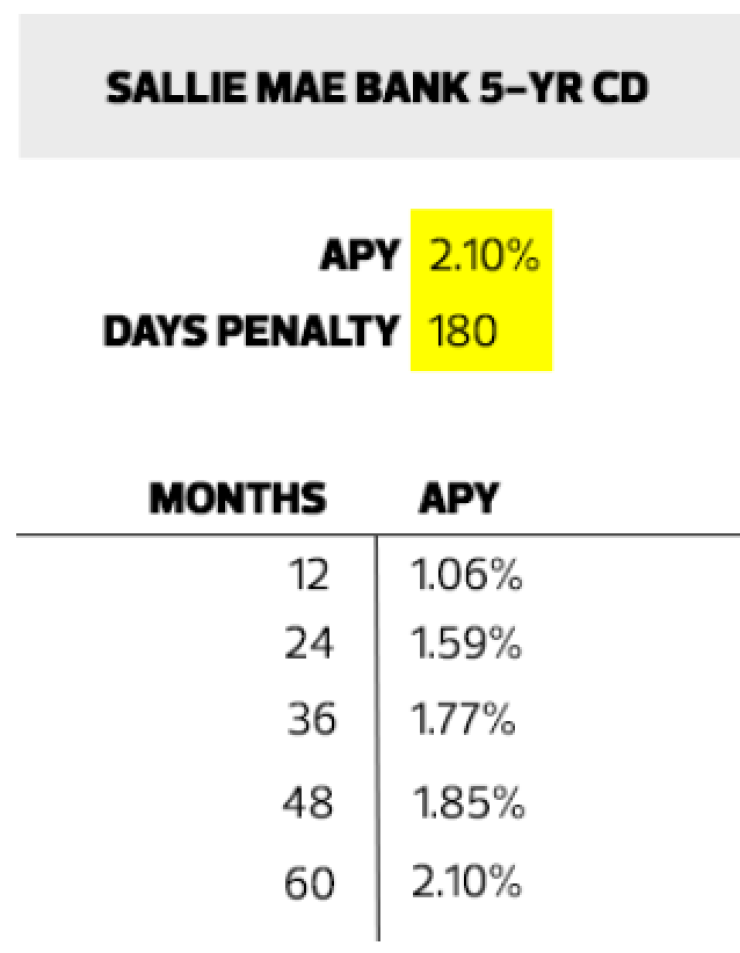

My core bond fund is the Vanguard Total Bond Fund (BND). It yields 2.28% as of March 7, and is 64% backed by the U.S. government. With a 5.7-year duration, that bond fund would lose about 3.4% if interest rates rose by 1 percentage point over the next year. Compare that to a Sallie Mae Bank five-year CD yielding 2.10% APY with a 180-day early withdrawal penalty. That penalty amounts to a put to sell it back to the bank at a 1.04% discount (a bit less than half a year). Thus, a 1 percentage point increase in rates would equate to a 1.06% gain rather than a 3.4% loss.

Counterpoint: The bond fund would increase if interest rates declined further, Kinniry parried. That’s true, although the CD would also be more valuable since it would be paying higher-than-market rates. Just because CDs aren’t priced daily doesn’t mean they can’t increase or decrease in value. I thought Kinniry was spot on that the bond fund would increase a bit more with a slightly longer duration than the CD. He also observed that my strategy takes far more additional time to manage than just keeping the cash outside of Vanguard. One most know when to break the CD and pay the penalty. The simple rule I use is to break the CD when you can earn twice as much as the penalty from breaking the CD over the remaining term of the CD.

Point: Paying off a mortgage is better than a bond fund or opening a CD.

I regularly tell my planning clients that a mortgage is merely the inverse of bond. When you own a bond or bond fund, you are lending money to an entity that pays you interest and your principal back. When you take out a mortgage, it’s the reverse. Paying off or paying down the mortgage is better than owning a bond in the taxable account as it’s always at least tax-neutral, and typically tax-advantaged, to jettison the bond and pay down the mortgage, as long as one has enough liquidity. I question the wisdom and practicality of lending money out at 2.28% (the rate of the Vanguard Total Bond Fund) and borrowing it at a higher rate.

Counterpoint: I’m missing the point, Kinniry insisted. Consider a hypothetical of an individual with a $1 million portfolio (60% stocks/40% fixed income) and $1 million home with $400,000 mortgage at a 3.2% interest rate. He argued one could likely make a greater return with that 60/40 split than the low mortgage rate.

I pivoted the hypothetical to viewing the situation this way: The investor actually had a home worth $1 million and a portfolio worth $600,000 that was 100% invested in stocks). As I see it, the $400,000 mortgage and the bond fund cancel out. One shouldn’t borrow the money at 3.2% only to lend it out at 2.28%. While Kinniry and I weren’t on the same page on the comparable bond fund to use (he advocated for corporate and muni bonds), we both agreed that it’s not a good idea to borrow money at a higher rate than one expects to receive from a comparable investment.

Point: I’m very tempted to invested in the Vanguard Managed Payout Fund (VPGDX) – but won’t. Most financial products are designed for accumulation, but I’m of the opinion that dying the richest person in the graveyard is a lousy goal. I was excited when Vanguard launched managed payout products in 2008. (More precisely, Vanguard launched three funds with different distribution rates; the funds later merged into a single fund that seeks a 4.0% annualized distribution, paid out on a monthly basis.) I love the idea of receiving a cash distribution without paying for an expensive insurance product.

Nonetheless, I don’t recommend it. Why? Because of what’s inside. It’s pretty much the opposite of a target date retirement fund with a few ultralow cost diversified index funds. It’s now comprised of nine different funds with an expense ratio of 0.42% -- roughly three times higher than the target date retirement funds.

The portfolio now includes the market neutral fund, which has an expected return of the risk free rate before fees; an alternatives fund; a global minimum volatility fund; a commodities fund; and even an overweighting toward emerging markets over developed international countries. I’m not saying everything has to be indexing, yet this goes too far in adding fees to try to outsmart the market, in my view. I’ve long hoped that Vanguard simplifies this fund and lowers the fees.

Counterpoint: “We believe that our active management, along with exposure to alternatives, have the potential to add value, particularly in periods when bonds don't add value,” Ameriks told me.

I told him that I had benchmarked the fund to a simpler allocation such as the Vanguard LifeStrategy Moderate Growth Fund (VSMGX). This fund is a simple, four fund broad index portfolio with a 60% stock and 40% bond allocation and an annual expense ratio of 0.16%. One could certainly argue that the managed payout fund has a different risk profile. According to Morningstar, since inception in 2008 through Dec. 31, 2015, the Managed Payout Fund earned 4.11% annually while the simpler Moderate LifeStrategy fund earned 4.44%. Looking backward, the simpler fund earned 0.33% more annually, just a tad over the current annual expense ratio differential of 0.26%. It was, however, not a good period for some of the alternative and commodities strategies.

Point: Vanguard’s risk profile questionnaire doesn’t measure the need to take risk. For instance, it has me pegged at 70% equities, though I’m holding firm at 45% equities. In my view, it didn’t measure my need to take risk.

Counterpoint: That’s true, Kinniry agreed, noting that the questionnaire is merely a starting point for a discussion.

Point: I’m wary of international bonds funds, such as Vanguard Total International Bond Index Fund (VTABX) because of higher fees and hedging costs.

Counterpoint: Since inception in 2013, VTABX it has outperformed the U.S. equivalent Vanguard Total Bond (VBTLX) and provided more diversification, Kinniry said.

Point: I wish the Vanguard Precious Metals and Mining Fund (VGPMX) hadn’t added non-precious metal stocks. I’d argue that low correlation to stocks is the primary reason to own the fund.

Counterpoint: This position has helped its performance over the last few dismal years for precious metals equities, though it underperformed last year.

The bottom line: My discussions with Vanguard were driven by the logic and math of our viewpoints. As is always the case, only time will tell who’s right.