I first met Jack Bogle about 16 years ago after I wrote him a letter thanking him for his work and telling him how much I’d like to meet him. A week later, I received a handwritten card telling me that he was going to be in my area in the next month and would be “pleased to set up a meeting.”

I arrived early at the Denver Sheraton, my heart pounding in anticipation. When he walked into the hotel’s restaurant and sat down, I noticed he looked a bit angry. “Mr. Bogle, is something wrong?” I asked. He told me he had just lost a dollar in the hotel vending machine and that he was going to the front desk to get that dollar back after our meeting.

That same degree of frugality had led Vanguard to lower costs relentlessly and had prompted my admiration, as well as that of millions of other investors and advisors.

A clue to why Bogle has become such leading light is found in his most-recent book, “Stay the Course — The Story of Vanguard and the Index Revolution.” In the memoir, he describes his Princeton University thesis from 1951, “The Economic Role of the Investment Company.” The thesis, surprisingly powerful and new for that time, later became the bedrock of his success.

- Investment companies should reduce charges and management fees.

- Funds do not beat market averages.

- They should serve the fund shareholders.

Still, a good thesis doesn’t automatically bring professional triumph. The following seven decades were marked by achievements — and failures — that further molded his beliefs.

After graduating, Bogle joined Wellington Management and quickly rose through the ranks, becoming its CEO just 13 years later. After a failed merger and in a bear market, Wellington’s stock plunged to $4.25 a share from a high of $50. In 1974, after 23 years at Wellington, the board abruptly fired Bogle, which he describes in the book as “the only heartbreaking moment” of his career.

Often, how someone handles failure defines them. This is particularly true for Bogle, I think. Though no longer employed by Wellington, Bogle was still chairman of the 11 Wellington funds. The day after his firing, he called a meeting of the funds’ boards, which eventually agreed to a mutualization of the funds. The new fund family would be called Vanguard, with Wellington the distributor and investment advisor of the funds.

Thus, the Vanguard enterprise launched with a crew of only 28. One year later, in 1976, Vanguard began offering the first “unmanaged” mutual fund — which would become the first S&P 500 mutual fund.

It was an inauspicious beginning. In his book, Bogle calls it a “complete flop.” Its initial capital investment was $11.3 million (in contrast to the $150 million targeted) and wasn’t enough to purchase 100-share lots of the 500 companies. He was able to buy stock only in 280 companies.

Bogle pressed on and, in 1977, convinced the board to eliminate all sales charges and assume responsibility for Vanguard’s own marketing and distribution.

The S&P 500 index fund failed at first to beat the average of other (active) funds. Critics were harsh, calling it “Bogle’s folly” and even asserting that index funds were un-American. Fidelity’s chairman, Edward C. Johnson III, famously said investors would not be satisfied with average returns. Even after merging another fund into the 500 index fund, Vanguard failed to attract much investor capital.

Opinion eventually turned around, of course, with competitors launching similar funds. Fidelity, for instance, floated its Fidelity’s Zero Index funds this year to try to catch up.

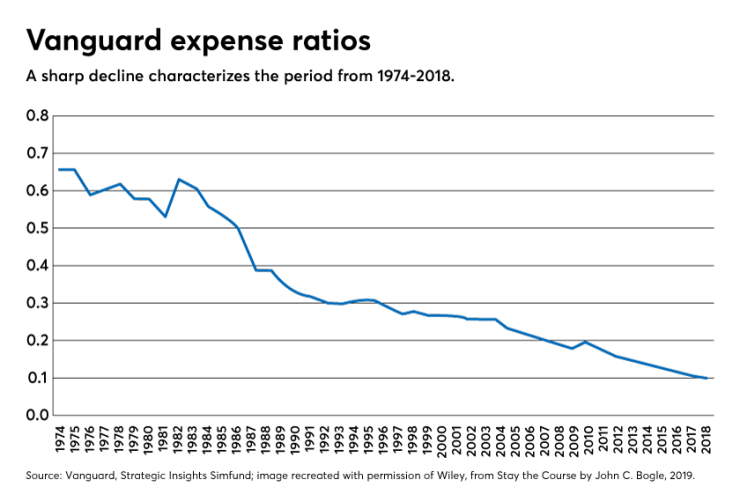

During his decades leading Vanguard, Bogle relentlessly drove expense ratios down from an average of 0.66% annually to 0.10% in 2018, as Vanguard assets hit $5.3 trillion. Bogle launched many new funds — the Total U.S. Stock, Total International Stock, Total Bond Index Fund, balanced LifeStrategy and target date retirement funds, tax-managed funds and active funds. They all had low fees and served one master: the fund shareholders.

Today, the Vanguard S&P 500 index fund is the second largest fund in the world, eclipsed only by the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index fund, an even broader low-cost index fund. As of October 2018, US equity index funds reached $4.227 trillion, or 47.7% of total US equity fund assets, according to Bogle’s office. His index experiment has caught on.

On Jan. 31, 1996, at age 66, Bogle stepped down as Vanguard CEO to receive a heart transplant. Yet this was still a far cry from retirement. He formed the Bogle Financial Markets Research Center to conduct research in finance, largely focused on the fund industry.

With offices at the Vanguard headquarters just outside of Philadelphia, Bogle went to work almost every day from his home nearby until recent illnesses halted the trips. He continued to work with Vanguard employees and celebrate anniversaries and retirements until just before his death today at age 89.

MY EXPERIENCES WITH BOGLE

Bogle changed my life — twice.

First, he gave me higher returns from years of investing in low-cost index funds he had spearheaded. This gave me the assets to feel comfortable to leave the world of big corporate finance and start my own hourly advisory firm.

When I went to that restaurant in the Denver Sheraton, I felt like I was meeting with the president of the United States, my favorite musician and actor all rolled into one.

I didn’t know what to expect given his age and the roughly six years that had passed since his heart transplant but Bogle was slender and energetic. Despite his irascible entrance, he was kind and generous with his time. Not surprisingly, he was quite candid. I was shocked when he told me he thought the Vanguard experiment was a “failure.” Stunned, I asked why and he said it was because no other mutual fund family had followed the same path of being owned by fund shareholders.

He quickly put me at ease and I felt free to bring up my investing mistakes, particularly that my first index fund was with the once giant Dreyfus fund family.

It was then he changed my life again. He encouraged me to aspire to the same principles in my practice that he had set out in his Princeton thesis and to keep things as simple as possible. He has told me several times to “press on regardless” in my hourly practice, which, like the index fund, was anything but an instant success.

If a statue is ever erected to honor the person who has done the most for American investors, the hands-down choice would be Jack Bogle.

Bogle and I have kept in touch every year since, and I found myself on the panel of experts every year at the annual

Vanguard funds are owned by its shareholders and the funds own Vanguard. Had Bogle decided to keep ownership, he’d be a billionaire, but perhaps not a legend.

In 2013, when I contributed to Knut Rostad’s book about Bogle called “The Man in the Arena,” I calculated he was saving investors $25 billion a year between the lower Vanguard fees and forcing competitors like Fidelity and Schwab to lower their fees.

Today, Bogle is saving people many times that amount. By giving investors a fair shake in keeping their share of the profits of capitalism, Bogle granted me and tens of millions of others the financial freedom to pursue our own happiness. Between 2014 and 2016, myself and about 10 others sent letters and emails to the White House and cabinet members to consider John C. Bogle for the Presidential Medal of Freedom. They went nowhere, but I remain steadfast in my belief that no one has done more to give millions of people financial freedom than Bogle.

To be sure, Bogle hasn’t been perfect. Some say indexing has become too large. But others have tried to copy his approach and have launched competing index funds. Bogle recognizes that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. I’m quite sure, however, many competitors still privately resent him as their market share and profits declined.

One of the very few investors with a long-term track record of besting the S&P 500 is Warren Buffett. He expressed his admiration for Bogle in the 2016

As for me, I don’t need a statue. I wake up every morning enjoying what I’m doing so much more than my days in corporate finance, and I owe it to Jack Bogle.