With Election Day upon us, the prospect of a new president in the White House in January seems a distinct possibility. For high-income earners — those households making $400,000 a year — the risk is palpable for both increased income tax and estate and gift tax per the Biden tax plan.

That’s why now is the time to reach out to clients about year-end tax planning. To avoid a post-election scramble for legal document preparation, start marshalling your resources and use political volatility as a marketing angle to attract prospects.

The tax planning ideas presented below can apply to high-net-worth clients, as well as all taxpayers who are looking to reduce their tax bills.

1. Remind your clients to maximize their retirement savings

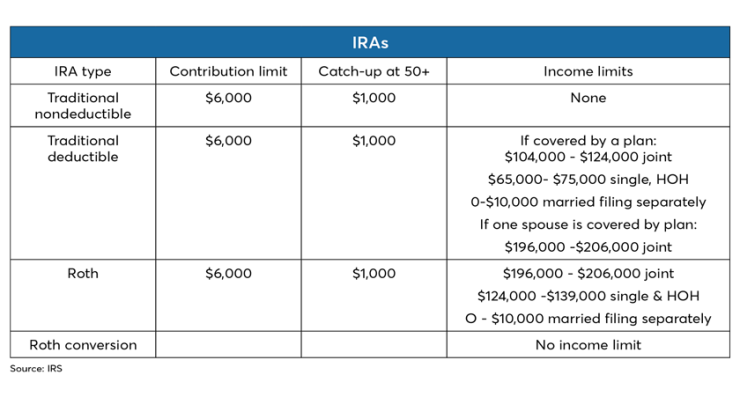

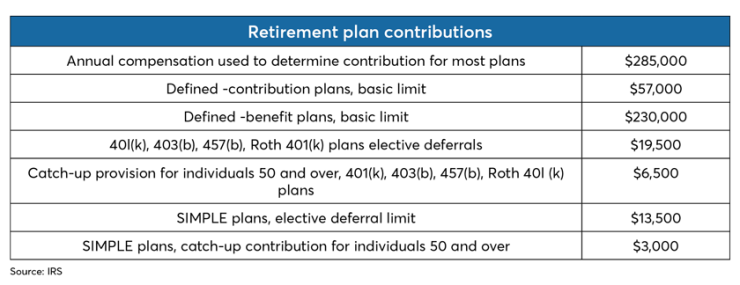

If your client turned 50 years old this year, they're entitled to make a catch-up contribution of $6,000 for their 401(k), if their plan allows. It’s not too late to catch up for 2020. too. Anyone with compensation can contribute to a traditional IRA (see chart.). It’s the deductibility of the IRA contribution that is subject to income limits. Just a reminder: Roth IRA contributions do have income limits that restrict the ability to make a contribution.

Come January, clients can make their 2021 IRA contributions. Why not consider making the IRA contribution at the beginning of the year? The advantage is that the money is invested sooner as opposed to waiting until April 2022, when most make their IRA contributions for the 2021 tax year.

2020 IRA & retirement plan contribution limits per IRS

2. Review where your clients are with capital gains and losses

Mutual fund capital gains distributions typically are announced during the fourth quarter. What — if anything — should your client do after taking distributions into account? If they are in the 22%-or-higher tax bracket, tax-loss harvesting may make sense. Your client can harvest losses in excess of their gains but are limited to taking $3,000 in losses in excess of gains. Losses not used in 2020 can be carried forward indefinitely for federal tax purposes.

For clients projecting a large ($1 million-plus) taxable gain over the next several months, one might consider accelerating the gain into 2020, if possible. Biden’s plan is to increase the long-term capital gain rate from 20% to 39.6%, according to

Another way to hedge the tax-rate increase would be to donate the asset to a charitable remainder trust and then sell, as there would be no immediate tax bill to the grantor. The income beneficiaries would pick up the gain income over their lifetime or a term of years, spreading the tax bill over many years and greatly reducing the risk of having gain income taxed at 39.6%.

3. Itemizing and charitable deductions

Most taxpayers will not be itemizing for 2020 due to the increased standard deduction, plus the fact that the state and local tax (SALT) deduction is limited to $10,000 for married and single filers. To itemize tax deductions, investors will need to exceed the standard deduction, which is something the government gives each taxpayer — and they don’t have to complete Schedule A itemized deductions.

2020 standard deduction amounts per IRS

Due to the high hurdle of itemizing deductions, charitable contributions will be a key factor in itemization.

Consider gifting appreciated securities instead of cash, a very tax-inefficient choice. Gifting stock with a fair market value of $5,000 with a cost of $1,000 could save $952 in tax ($4,000 x 23.8%), plus your client still receives a charitable contribution deduction. The top federal long capital gain rate is 23.8%, including the Medicare surtax.

Biden has proposed itemized deductions be limited to 28% per dollar of deduction for those earning greater than $400k of adjusted gross income (AGI) (2). Those taxpayers should consider accelerating charitable giving into 2020 where they could receive 37% per dollar of deduction.

4. Qualified charitable contributions (QCCs) for 2020

For the 2020 tax year, certain cash contributions do not have any adjusted gross limitations, meaning 100% of the contribution is deductible.

QCCs under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act are those that:

— Are made in cash.

— Are made where a charitable deduction would otherwise be allowed.

— Go directly to an eligible charity under 170(b)(1)(A), such as a church, synagogue or organization like the United Way.

It’s important to note that contributions made to a non-operating private foundation or a donor-advised fund (DAF) do not qualify as qualified charitable contributions. The 60% AGI limitation would apply here for cash contributions.

5. Pairing the QCC with a Roth conversion

Philanthropic taxpayers with traditional IRA accounts should consider a 2020 Roth IRA conversion. Qualified charitable contributions made during 2020 could offset 100% of the income recognized on such conversions.

6. Federal tax rates are historically low — but may not stay that way

This might be a good time to take advantage of the lower tax rates and consider doing a Roth conversion by Dec. 31, 2020. Roth conversions don’t always carry a tax bill, and taxpayers can mitigate the tax bill by pairing tax strategies. For instance, if your client has been affected by COVID-19 and is in a lower tax bracket, this would be an opportune time to consider a Roth conversion. Remember, there are no income limits for Roth conversions, nor is there a limit on how much you can convert.

Fees among the leaders range from as little as two basis points to as high as 125 basis points.

7. Upstream planning

Generally, When a person inherits an asset, the basis becomes the asset’s fair market value at the time of the owner’s death. This is called a “step-up in basis” because the basis of the decedent’s asset is stepped up to market value. Upstream planning is making gifts to older family members of low-basis appreciated assets. If the donee lives more than a year, and leaves the assets to the donor at death, the donor’s basis is the fair market value of the asset at the donee’s date of death (a stepped-up basis). (See IRC 1014(e).)

Conversely, if the donee dies within one year, the donor’s basis reverts to the donor’s basis value before the gift, (no basis step–up). Consider, providing an alternative beneficiary (i.e. a grandchild) in the event the donee does not live the year, there would be a basis step-up since the property went to someone other than the donor. Note that this strategy is contingent on making sure that the donor has gift exclusion available, and the donee will not have a taxable estate.