Finding a niche can help planners build their businesses — but advisors looking to serve female clients better may need to be careful how they use that term.

A little over half of the U.S. population — roughly 166 million people — are women, many of whom control their families’ wealth. Given the sheer number, it’s vital that advisors recognize how women’s planning needs are different from men’s while being careful not to lump them into a singular group.

It’s a common oversight, however, given how many planners seek to distinguish their practices based on specialities. Niche-based planning is now so widespread that it’s become Practice Management 101, according to Kate Healy, managing director of Generation Next at TD Ameritrade Institutional.

“When somebody starts the business, they work with everybody,” she says. “As the business grows, they find clients that share their values. ... That’s the type of client you should be working with. It’s not a gender.”

It makes sense that advisors target women clients. Almost 70% of married women believe they’ll outlive their spouses, according to a 2018 UBS InvestorWatch survey. For advisors, the inevitable transfer of wealth provides both a challenge and opportunity. While some women do have unique planning needs, all their needs stretch beyond gender.

“If you truly want to be successful in providing value to your clients and prospective clients, it’s all about addressing ... the problems they’re facing,” says Melissa Sotudeh, director of advisory services at Virginia and Maryland-based RIA Halpern Financial.

She starts by identifying whether her clients are undergoing big transitions: divorce, parenthood, landing a high-powered job or choosing to take time off. “Those right there, to me, are the niches.”

Simply assessing a client’s needs by gender can lead to bias in how an advisor approaches their relationship, says Carol Fabbri, managing partner of Fair Advisors outside Denver and the founder of Fair Advisors Institute, a nonprofit devoted to spreading financial literacy.

“You start making assumptions that women all react one way,” Fabbri says. “We just don’t.”

Instead, advisors should focus on non-gender-based niches; this allows them to specialize on clients’ specific pain points. “You can’t do that when your group is as large as just women,” Fabbri says.

But does working with female clients require a different approach in general? Ultimately, it boils down to thinking about what women need, Healy says.

“They live longer, they’re generally paid less, they have kids and it’s sometimes necessary for them to take a break in their work, so they may not have the same retirement needs than men do. That doesn’t mean it’s a niche,” she says.

At the same time, focusing on those needs can help planners craft a specialty that could serve men as well as women, says Phoenix-based advisor Michelle Buonincontri, who is also a Certified Divorce Financial Analyst.

“To me, ‘niche’ says or implies a new way, a different way, a departure from business as usual,” says Buonincontri, the founder of Being Mindful in Divorce, a practice that focuses primarily on helping families navigate divorces. “I don’t think it’s a bad thing necessarily.”

Buonincontri says that focusing on how clients communicate is key — and gender does factor into that.

“Let’s be honest, men and women communicate and socialize differently. Anyone who’s been in any kind of relationship with the opposite sex knows this,” she says. “We know that wealth management is really focused on men because they controlled the finances [in the past.] There’s a broader cultural shift as we see women transitioning to inherit more wealth.”

Women currently control 51% — or $14 trillion — of personal wealth in the United States, according to 2015 data from BMO Wealth Institute. That number is expected to grow to $22 trillion by 2020, the data show.

By 2028, women will control 75% of discretionary spending around the world, according to data from EY Global Wealth & Asset Management.

To attract more female — and male — clients, Sotudeh identifies ways to break from tradition. Dual-income households have evolved, she says. At the same time, financial advice is undergoing its own evolution.

“When you break it down to what women are looking for in an advisor, a lot of the time it is multifaceted and lends itself to more of a relationship instead of a transaction,” she says. “The whole industry is moving toward this relationship model of no commissions, no brokers — everything’s about a longer-standing advisory relationship.”

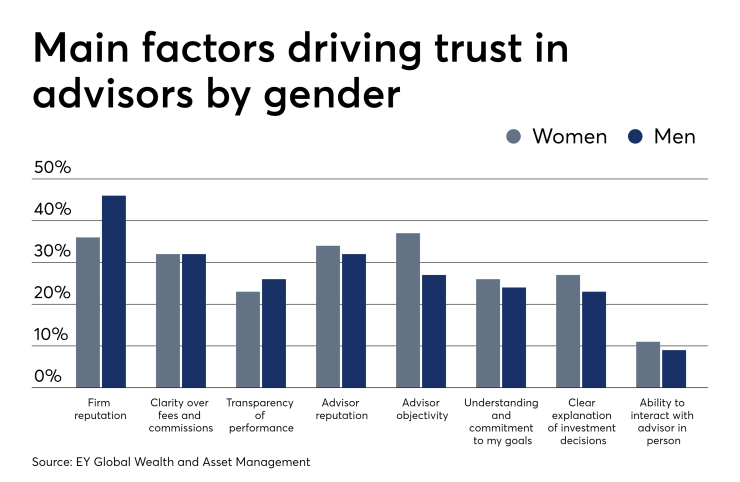

In the financial services industry, women are often categorized as more risk averse than men. While a 2016 EY Global Wealth & Asset Management study showed that women place greater emphasis on advisor transparency around investment performance, the survey found “little evidence to support common assumptions about women investors, such as a lower risk appetite or an attachment to ethical investing.” But making financial decisions based on risk may not be a bad thing regardless of gender, according to New York-based CFP Martisha Patterson of PattersonPlans Financial Planning.

“Anyone should take calculated risk as a way of gathering information,” says Patterson, who is also co-chairwoman of the Metro NY FPA chapter. “Advisors need to take their time to understand [a client’s] position or perspective as a woman. Don’t brush everyone with the same broad brush.”

ADVISOR DIVERSITY

There’s one way the wealth management industry can be more inclusive and welcoming to women, however: Address the lack of gender diversity within its professional ranks.

A lot has changed since 2006 when Catherine Valega first started working as an advisor. But one thing noticeably hasn’t.

“Thinking back to when I started working in financial services and now, I don’t think the percentage of women has increased at all,” she recalls.

Valega isn’t wrong. While the number of women CFPs went up 3.6% to 19,248 in 2018 from 18,578 in 2017, they make up just 23% of professionals holding the designation, according to data from the CFP Board. That percentage hasn’t budged for over a decade, data shows.

The CFP Board found that among financial services executives, 41% of those surveyed believed that men are more likely to have the characteristics needed to be successful planners — compared with 7% of respondents who said women had such an advantage, according to a 2013 white paper by the board’s Women’s Initiative.

However, 82% of the same executives said that women have an advantage when it comes to attracting female clients.

When Valega, who works at Boston-based Sapers & Wallack, talks with client couples about how they will manage their finances if the husband becomes incapacitated, she finds her perspective often helps.

“I know how to make women feel comfortable,” Valega says. “But there’s not enough of us out there for the amount of assets that are going to be in the sole hands of women and that are already in the hands of business owners.”

Women are the primary earners in 40% of American households — a number that has increased fourfold since 1960, the BMO data shows. Additionally, 30% of all private businesses are controlled by female proprietors, the study said.

This doesn’t mean that women should work only with women. For male advisors, that might mean taking extra time to make sure both spouses are involved when meeting.

“The advice I would give men advisors is that even if the woman isn’t leading the financial decisions now, there is a good chance they will be in the future. I never assume the woman isn’t the decision maker based on my experience,” says Ashley Folkes, a male advisor and complex manager at Phoenix-based Moors & Cabot. “I have cases where I have turned down appointments until the spouse is able to make the appointment as well.”

Dominantly male practices should recognize that women clients are looking for advisors who understand their financial situations.

“If a client walks into an office and everyone there is so different from themselves, they don’t believe they’re going to be understood or taken seriously,” TD’s Healy says. “It’s not a requirement, but women prefer to work with someone they can trust who understands their situation — regardless of gender.”

It’s harder to get the message across if the firm’s advisors are all men. “You have to make sure you’re showcasing women, you’re hiring women, you have women on your team in a leadership role. If you can’t hire diversely, you’re not a top-tier firm,” she says.

The gender makeup of Sotudeh’s firm, Halpern Financial, is noteworthy. The firm’s commitment to hiring women was one of the reasons she signed on.

“It was pretty exciting because the firm looked much different — even six years ago — than what your typical independent RIA was structured like,” Sotudeh says. “I signed on, hired some more women. We just continued to grow and now we’re a group of 11. Nine of us are women.”

Indeed, greater representation among advisors may increase awareness of planning as a service to a broader population, Patterson says. “Representation matters, and we really need to break down how we communicate with folks,” she says.

As an African-American advisor, Patterson says she’s noticed an influx of women and people of color seeking financial advice from a variety of sources — from influencers to so-called financial coaches — who may not have the expertise they need.

“I think education, targeting these diverse groups in terms of gender and race, and making the CFP designation more accessible to those groups — those three things would really attract both diverse planners and diverse clients,” she says.

Patterson says she thinks every advisor should undergo sensitivity training. “People should be able to share common experiences as opposed to what makes us different. I think we all need more of that,” she says.

Ultimately, the key is to recognize that every female — and male — client is different. Advisors hoping to find a niche should avoid making macro decisions based on gender, Healy says.

“No two clients are the same. You can’t just simplify everything, or make it pink, or talk down to a woman. Ask who it is you’re talking to,” Healy says. “Get to know your client and find out what those interests are. Getting to know your client well is how you deliver the best experience.”