When it comes to where things stand for women-led fintechs raising venture capital funding in 2022,

The good news is that there has been an influx of early-stage capital from women investors, some specifically targeting women and underrepresented founders.

The bad news for diverse fintech founders like herself is that the venture investments that women investors make and that women CEOs raise typically reside in more traditional, women-focused consumer businesses.

Translation: Not fintech.

The worse news is that this influx has yet to translate into more late-stage funding, which is crucial because fintech can be more capital-intensive than other businesses.

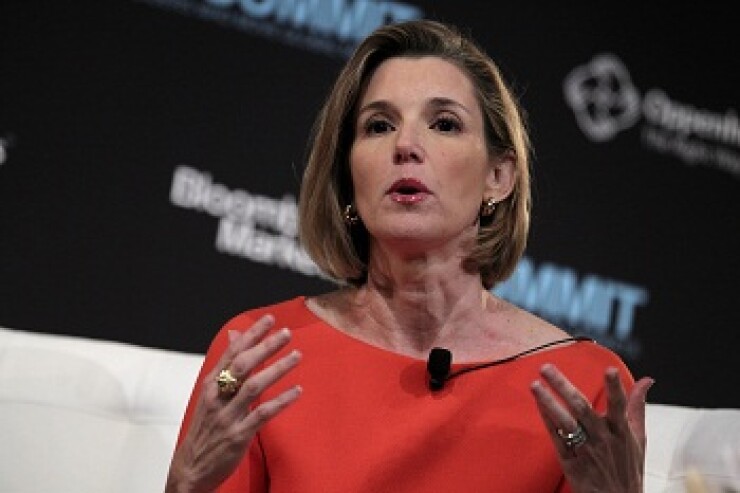

“In my experience, it's been because few women investors are in roles today to write bigger checks,” said Krawcheck whose storied Wall Street career includes leading Merrill Lynch Wealth Management, Smith Barney, Sanford Bernstien and Citi Private as CEO. “Also because, and this is actually pretty gutting, raising early-stage capital investing from women investors can sometimes make it harder for women CEOs to get the next round of funding. The research indicates this is pure bias on the assumption that you weren't good enough to get funding from the guys. This is despite the research indicating that women-run businesses provide as good or better results than all-male teams on less capital.

“The implications? Significant, considering that financial services is our economy's lifeblood.”

Krawcheck, who founded Ellevest in 2014, knows about getting to that next round of funding. Earlier this year, her company completed

“Women raise just 1% of series B dollars across industries, and just 1% of fintech dollars across all stages,” she said. “That math means you can count women-run fintechs who got this far on your fingers. Literally, on your fingers.”

Krawcheck shared insight on the state of diverse fintech funding during a recent Task Force on Financial Technology hearing convened by the

Titled “Combatting Tech Bro Culture,” the virtual hearing brought together five experienced fintech and VC professionals to discuss the barriers blocking investments to diverse-owned fintechs and why knocking them down is beneficial to more than just the underrepresented.

Krawcheck was joined on the panel by Jenny Abramson, founder and managing partner of Rethink Impact; Marceau Michel, founder of Black Founders Matter; Wemimo Abbey, co-founder and co-CEO of Esusu; and Maryam Haque, executive director of Venture Forward.

“Research shows that companies led by diverse senior leadership outperform those that are led primarily by white and male leaders, yet venture capital funding for new fintech companies goes overwhelmingly to those founded by white men,” said Congresswoman and Committee Chair Maxine Waters, a Democrat from California. “In fact, only 2% of venture capital funding went to women founders, only 1% to Black founders and only 1.8% to Latinx founders. Venture capital can mean the difference between success and failure for new fintech, and we can all benefit from promoting diversity in future fintech.”

Michel said much like the end of legal slavery, racial integration and affirmative action, measurable and accountable methods are needed to facilitate positive change. He points out that while those efforts have not created parity in America, they have enabled social progress.

“What I’m asking is that you consider how our society and lawmakers are holding the venture investment industry accountable to finally integrate in a meaningful way,” he said. “There have been many empty vows to improve the abysmal statistics of diverse investment. However, there has been no significant movement or effort to truly diversify by including women and (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) founders in their portfolios. This is unacceptable, so I took action.”

In June, Michel launched the

Michel said the goal was to give funds a clear objective to work toward, stating that without measurable intentionality, there will be no change or improvement.

“Classist tech bro culture has weakened our economy and limited the solutions that diverse founders are creating. Discrimination based on socioeconomics and network is what’s allowed this to prevail,” Michel said. "My experience investing in Black founders has only proven this to be true. After making my first five investments in ventures led by Black men, I made a specific choice to only look at deals led by Black women. This effort led to investing in superstars like Olympian Allyson Felix and other incredible companies founded by Black women.”

He adds that communities of color have had little choice in the financial institutions and companies that serve them. Michel said fintechs that claim to serve and target such communities without any level of representation or connection to those communities are committing a form of financial manipulation that keeps the status quo alive and well.

“Dismissing the lived experiences and perspectives of diverse founders is a detrimental mistake. It’s these lived experiences that inform the products we create with the specific needs of our communities in focus. This leads to better outcomes and services for all,” he said. “We’ve repeatedly seen women and BIPOC founders prove more capital-efficient and yield higher returns. This should lead to an increase in interest in such ventures. However, investing in and working with said founders exist outside the comfort zone for most VC funds.

“If legislation can’t be put into place to integrate fintech financing, how can the emerging diverse founders in this space be empowered?”

Empowerment was the force driving Carmelle Cadet forward as she began her career in fintech and financial services. Founder and CEO of

“I was born and raised in Haiti up until I was 16 years old, and I moved to the U.S. I remember getting so blown away by the concept of financial services in the U.S. And I always had in my mind that I need to go back to emerging markets to build better financial markets because people should not be locked out or excluded from financial services just because of where they're from or just because of how much money they make,” she told Financial Planning.

Cadet, who spent a decade at IBM before founding Emtech, became an expert on technological infrastructure, privacy and the financial inclusion implications of central bank digital currencies because she knows that the established system runs on exclusion at some level. Her goal is to provide greater financial access and understanding to underserved communities.

But the road to funding for a Black woman-led fintech created to open the gates of financial services to an untraditional client base was not an easy one.

What she describes is familiar to countless people of color trying to achieve success in business, or life — working twice as hard to get half as far.

“I see other companies that are raising funds while doing way less than we did. I bootstrapped the company on a contract that we won for two years and then went on to win a major central bank contract on our own,” she said. “We know what problem to solve, and we know how to do it, but VCs have not always jumped on board, so it's been a very difficult fundraising process for us. Especially when we look at the comparison of white males that are serial entrepreneurs who have networks and can get funded with the back of a napkin.”

But Cadet’s desire for things to be better is not self-serving. She believes deeply in the universal benefit of more diverse kinds of people creating fintech solutions, and she wants the next generation of creators to have an easier road than she did.

“Hopefully my success is an example that shows them they can do it,” she said. “And all the scars that I have … all the teary eyes and crying sessions after being told ‘no’ 50 or 60 times in a week. You can get discouraged very easily. I’ve had my moments.”

Life experience and increasing access are also key motivators for Asya Bradley, co-founder and chief operating officer of

Like Cadet, Bradley immigrated to the United States. But she did so after years as an international businesswoman who achieved success across Europe, Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

Despite her experience, the roadblocks she faced because of who she was and where she came from remained.

“As a queer woman of color, I've had to face a lot of the different stigmas that are associated with that. But when I did move to America, I couldn't even open up a bank account, and I realized that was just my first barrier to entry and my first barrier to being able to do anything,” she told Financial Planning. “That's kind of what got me started. If someone who is educated, well traveled … a business executive with a great credit history outside of this nation can't even open a bank account, what are Black people who are born and raised here facing? What are people who are maybe coming up from Latin America who have language-barrier issues facing. That got me on this journey of trying to think about financial inclusion and seeing where the systemic bias and this racism essentially start.”

A mother with Black children, Bradley also felt a need to make an impact sooner rather than later after the tragic murder of George Floyd. She said the cries Floyd made to his mother still pierce her heart and make her think of her own children’s ability to thrive and survive in this nation.

“I thought, I can't do this anymore. I cannot just sit here and have my job and think someone's going to do this,” Bradley said. “We are the ones that have to lead the way forward, so I quit my day job and quit everything that I was doing and started First Boulevard.”

With her experience, connections and a lot of hard work, Bradley said she was able to raise $20 million dollars within 11 months to launch Kinly. She now feels a great deal of responsibility to act as an angel investor in support of other underestimated founders.

To that end, Bradley has gotten involved in the VC space, working with organizations like the

“We've been sitting here begging for money from the VC funds, but as Maxine Waters says, we don't have the VC representation. So we know VCs are investing in the people that look like them,” Bradley said. “And there's enough capital within our communities that if we truly believed in our own strength and power, we could accomplish so much. But we need to believe that in ourselves.”

She also has strong advice for other women and people of color looking to support diverse-owned fintechs in a way that VCs currently fail to.

“Don't wait to be invited to the table. Build your own f****** table,” Bradley said. “And once you've built that table, bring your people to that table. Forget the whole scarcity mindset. It's not a Clarence Thomas situation where there can only be one of us in the room. So go ahead and bring as many of your brothers and sisters along, and make it your responsibility.”

For Krawcheck, the answer to the problem isn’t women entrepreneurs to start working harder. They already are. She added that the issues go well beyond the frustrations of founders who can’t get funded.

With 98% of mutual fund assets managed by men, 86% of financial advisors being men and 75% of senior leaders being men, women say they don't feel seen by the industry and rank it among the lowest of any industry they engage with.

She said when she was running Merrill Lynch, the vast majority of women who worked with them withdrew their money from the company in the year after their spouse’s death.

“And so women, as individuals, invest less of their wealth than men do, giving up returns that the markets have provided over time. This is one big reason for the gender wealth gap, which sits at 32 cents to a white man’s dollar and 1 penny for Black women,” Krawcheck said in her opening remarks during the June 30 hearing. “Think, too, of the businesses not founded, and so the needs that are not met. The investments that have not been made that would have built a more secure future for women and their families. The economic growth we could have seen had that wealth been created. Think of the toxic relationships so many women are stuck in. The dead-end jobs they can’t leave. The small businesses they can’t start … because they simply don’t have the money to.

“Is this something that any of us want for our daughters?”