The

The change will impact many beneficiaries who will have to distribute funds from their inherited account(s) within 10 years after the year of the owner’s death — much faster than what was previously allowed under the stretch provision, which allowed beneficiaries to spread distributions out over their own lifetimes.

While the old pre-Secure Act rules for designated beneficiaries still apply only to a newly created group of eligible designated beneficiaries — i.e., they are still permitted to stretch — any designated beneficiary who is not an eligible designated beneficiary is subject to the new 10-year rule.

Additionally, there are no direct changes to the rules for non-designated beneficiaries — that is, they remain subject to the 5-year rule when death occurs prior to the decedent’s RBD, or to the decedent’s life-expectancy rule when death occurs on or after the RBD that already applied.

Understandably, the legislation's elimination of the stretch provision also will greatly impact retirement account owners. Fortunately though, advisors have strategies available to help their clients mitigate the tax impact for those affected by the new rule.

Strategies aplenty

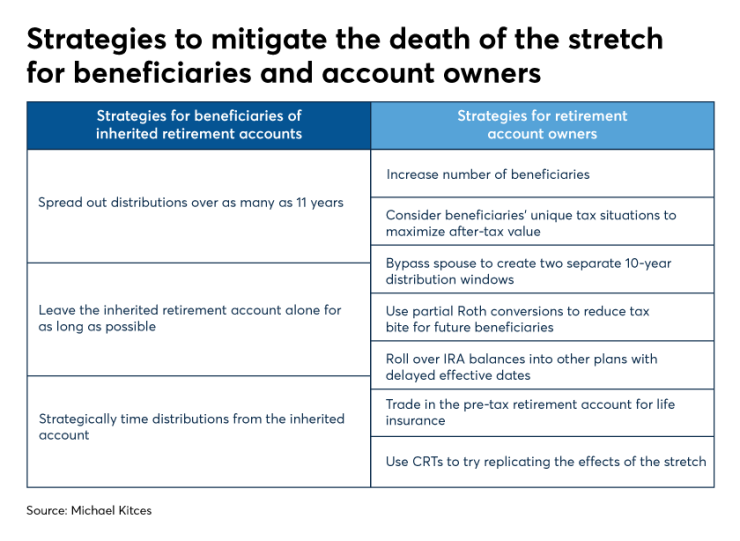

Advisors, retirement account owners, beneficiaries and potential future beneficiaries are all thinking about what must be done to minimize the income tax bite now that the stretch is gone.

Some strategies to help mitigate its disappearance are best implemented by owners of retirement accounts before they die. Regardless of the actions an owner takes or doesn’t during their lifetime, there are a variety of strategies that advisors can use to help their clients maximize the after-tax value of their inherited retirement accounts.

One tactic involves simply having the beneficiary leave the inherited funds alone for as long as possible.

While distributions before the 10th year after death

Thus, a beneficiary could avoid taking any distributions through the first nine years after death, and only in the 10th and final year distribute all the funds in the inherited account in one fell swoop. Doing so would allow a beneficiary to preserve the tax-deferred wrapper of the inherited account for as long as possible.

Of course, such a strategy also has the potential to backfire. Big time.

If an inherited retirement account plus any growth during the 10 years following death is sufficient to push the beneficiary into a much higher tax bracket by having all of the income compressed into a single year, a leave-it-alone strategy doesn’t make much sense.

Suppose a non-eligible designated beneficiary inherits a $250,000 IRA. If we imagine that the beneficiary is able to earn 7% per year, using

Conversely, taking the funds out annually would have resulted in distributions of only about $35,000 per year to amortize the $250,000 plus 7% growth over the 10-year period. In other words, it’s far easier to remain in the same tax bracket at $35,000 per year than it is with $500,000 in one year.

But while such a let-it-ride approach may not generally be the best path forward for non-eligible designated beneficiaries, there are several instances where it should be given very strong consideration.

For beneficiaries of Roth accounts

The new 10-year rule for designated beneficiaries applies equally to both Roth accounts and pretax accounts, as while the tax treatment of the distributions may differ, the obligation to take distributions is the same.

Thus, while a non-eligible designated beneficiary of a Roth account may take distributions before the end of the 10th year after death, they don’t have to. And the longer the Roth beneficiary leaves the money in the inherited Roth account, the longer the funds in the account can continue to grow tax-free.

Absent the need to take distributions to support living expenses before the end of the 10-year window after death, the standard operating procedure for a Roth beneficiary should be to avoid any distributions until the 10th year after death.

For beneficiaries already in the highest-income tax bracket

If a non-eligible designated beneficiary is already in the highest income tax bracket of 37%, it likely makes sense to delay distributions from their inherited retirement account. Regardless of how much income leaves the inherited retirement account at the end of 10 years, it can’t push the beneficiary into a higher income tax bracket if they’re already in the highest one. Additionally, few taxpayers benefit more from the power of tax-deferred growth than those in the highest bracket, who face the highest

Of course, high-income non-eligible designated beneficiaries looking to utilize this approach should keep an eye on Washington. If, for instance, we approach the end of 2025 and it appears that changes to individual income tax rates made by the

For beneficiaries of small pretax balances

A final group of beneficiaries who may wish to delay taking distributions from their inherited retirement account for as long as possible is one that inherits smaller balances that are not likely to push them into a higher tax bracket, even after 10 years of earning. For instance, if a non-eligible designated beneficiary inherits a $15,000 IRA account, even if the account doubles over the ensuing 10 years before a distribution occurs the resulting $30,000 distribution in Year 10 may not be large enough to push the beneficiary into a materially higher bracket.

Spreading out distributions

While waiting until the end of the 10-year period following the year of death may be a valuable approach for some individuals, many non-eligible designated beneficiaries will benefit from an approach that allows them to spread the income from their inherited account over as many years as possible.

To that end, while non-eligible designated beneficiaries inheriting after the Secure Act’s effective date are subject to the 10-year rule, in most cases they may also have the option to spread distributions from the inherited retirement accounts over as many as 11 tax years.

So how can those subject to the 10-year rule get an 11-year period to spread distributions? Recall that Year One of the 10-year rule begins in the calendar year following the year of the retirement account owner’s death. But what about the year of death?

If death occurs early enough in the calendar year, a beneficiary should have more than enough time to establish an inherited IRA and take a distribution from that account prior to the end of the year. That would allow them to take a distribution in what is essentially Year Zero of the 10-year rule. Additional distributions can then be made over the ensuing 10 years, allowing the beneficiary to spread the income from the inherited account over 11 tax years.

Of course the later in the calendar year that a decedent dies, the more challenging it may be to pull off this strategy. For instance, in the case of death on Dec. 31 there is no chance that a non-eligible designated beneficiary would be able to take a Year Zero distribution. Nevertheless, for most deaths occurring prior to December, advisors can engage in tax planning for the beneficiary with ample time to establish an inherited retirement account for the beneficiary and to coordinate a distribution prior to the end of the year.

Assuming decedents will die at a roughly even rate over the course of any given year, more than 90% of non-eligible designated beneficiaries each year can be expected to have the opportunity to spread income out over as many as 11 tax years.

And while 11 years certainly isn’t the multi-decade timeframe that many such beneficiaries would have enjoyed prior to the passage of the Secure Act, spreading out income over those 11 years will still be an effective way to minimize the potential risks of bumping into a higher income tax bracket as the retirement account must be liquidated.

Example 1: On February 2, 2020, an IRA owner died, leaving his $2.5 million IRA to his two children, Jack and Jill, in 50% shares. Jack is married and together with his wife has $100,000 of taxable income. Jill is also married and together with her husband has $175,000 of taxable income. Both Jack and Jill would like to minimize the impact of taxes on their respective inherited shares.

Assuming Jack and Jill are able to earn a 7% annual return, spreading out the income from their inherited shares over 11 taxable years would require them to take just over $150,000 from each of their shares annually. Surely this would cause them to pay tax at a significantly higher rate, right? Actually, not so much.

Let’s look at Jack, whose $150,000 annual IRA distribution, on top of his existing $100,000 of taxable income, will put him at $250,000 of taxable income. A peek at the 2020 tax brackets will show that the 22% bracket runs from $80,250 to $171,050, at which point the 24% bracket kicks in. As such, only $71,050 — or nearly half of Jack’s additional $150,000 of income from the inherited IRA — would be taxed at his current income tax rate of 22%. And only the remaining $78,950 would be taxed at 24%, a relatively small bump up from his usual 22% rate.

Meanwhile, Jill will have a total of $325,000 of taxable income after her $150,000 inherited IRA distribution is added to her $175,000 of existing taxable income. The 2020 tax brackets show that the 24% bracket begins at $171,050 and ends at $326,600. Thus, despite adding $150,000 to her normal taxable income, Jill will not see her marginal income tax rate increase at all.

Strategically timing distributions

Spreading the income from an inherited retirement account evenly over a 10-year or 11-year period can be an effective strategy when a non-eligible designated beneficiary’s income and deductions are expected to be relatively stable over that time period. But in many instances that’s not likely to be the case.

In situations where a non-eligible designated beneficiary expects significant swings in income and/or deductions, distributions from the inherited retirement account should generally be structured to coincide with periods when other income will be lower and/or when deductions will be higher.

Example 2: Bruce is a non-eligible designated beneficiary who inherited a $500,000 IRA from his mother on Jan. 18, 2020. Bruce is currently employed and earns roughly $150,000 per year, but plans to retire at the age of 65.

Consequently, it would make sense for Bruce to avoid, or at least minimize, distributions from his inherited IRA until the year after he retires.

For instance, he may opt to take no distributions from his inherited IRA during the first four years after his mother’s death — 2021 to 2024, during which he will turn 62 to 65 — and instead spread the income from the inherited IRA over the final six years of the mandated 10-year period.

Not surprisingly, there are many scenarios where lumping taxable distributions from inherited accounts over some number of years — as opposed to spreading them out more evenly over the 10 or 11 possible tax years — will make sense. Possible instances include when the following events will take place within the period covered by the 10-year rule:

- The beneficiary or the beneficiary’s spouse will be retiring or cutting back at work, such that employment income is expected to drop materially;

- The beneficiary or the beneficiary’s spouse will be going on Medicare, given Part B and Part D

IRMAAs generally look at income from two years prior; - A child will be applying for student aid;

- The beneficiary plans to move to a materially higher- or lower-income-tax state;

- A large charitable gift is planned;

- The disposition of a passive investment with suspended losses is expected;

- The beneficiary intends to marry someone with modest income, such that they can benefit from the lower tax rate of their married-filing-jointly tax brackets;

- The beneficiary is married to someone who is expected to pass away within the 10-year period, or is themselves expected to pass away and leave their inherited retirement account to their spouse; or

- The beneficiary is a child who will age out of the kiddie tax and have a lower income tax rate than that of their parents after that transition.

Adjusting estate plans

While advisors can implement planning strategies for non-eligible designated beneficiaries such as those described above to minimize the impact of taxes on an inherited account, they can also help account owners themselves adjust estate plans during life to account for the Secure Act’s changes to the post-death distributions.

Perhaps not surprisingly, retirement account owners have a wider variety of planning strategies available to them to mitigate the discontinuation of the stretch when compared to non-eligible designated beneficiaries, whose array of strategies can be summed up as different flavors of timing strategies.

One simple strategy for advisors to use with retirement account owners is to increase the number of beneficiaries named on the beneficiary form.

Example 3: Gordon is an 80-year-old IRA owner reviewing his beneficiary designations. Gordon’s two adult children currently are equal beneficiaries of his $2 million IRA.

Suppose that each of Gordon’s children has three adult children. Instead of leaving his $2 million IRA entirely to his two children — who, given Gordon’s age, are likely in their peak earning years — he might decide to leave 5% of his IRA to each of his six grandchildren and 35% to each of his children, reducing each adult child’s shares and the amount they have to fit into their tax brackets each year by 30%.

Of course there was nothing preventing Gordon from doing this before the Secure Act, and he may not want to leave any of his IRA to his grandchildren. Perhaps, like many individuals, he feels that he will provide for his children and then he will let his children provide for their children.

On the other hand, given the Secure Act’s changes, Gordon may now prefer to see some of his IRA dollars go to other beneficiaries to minimize the cumulative impact of taxes on his legacy. At the very least it’s worth a discussion.

Related, taxpayers who think of leaving IRA or other pretax retirement funds directly to young beneficiaries should remember that taxable distributions from IRAs and other retirement accounts are counted as unearned income. Thus, they may become subject to the kiddie tax, which after the Secure Act is taxable at the parent’s marginal tax rate. In such situations the benefits of adding a grandchild as an additional beneficiary to spread income over an additional return may be virtually eliminated, and the dollars end out being taxed at their parents’ tax rates anyway.

Distributions from inherited Roth accounts will generally be tax-free to beneficiaries, regardless of their own unique tax situation. As a result, heirs who are designated as equal beneficiaries of a Roth account receive equivalent after-tax value from the account.

The same, however, is not true for pretax retirement accounts left to beneficiaries with substantially different income tax brackets. In such instances the greater the income tax rate of a beneficiary relative to the other heirs, the lower the after-tax value they will receive from the account relative to those heirs.

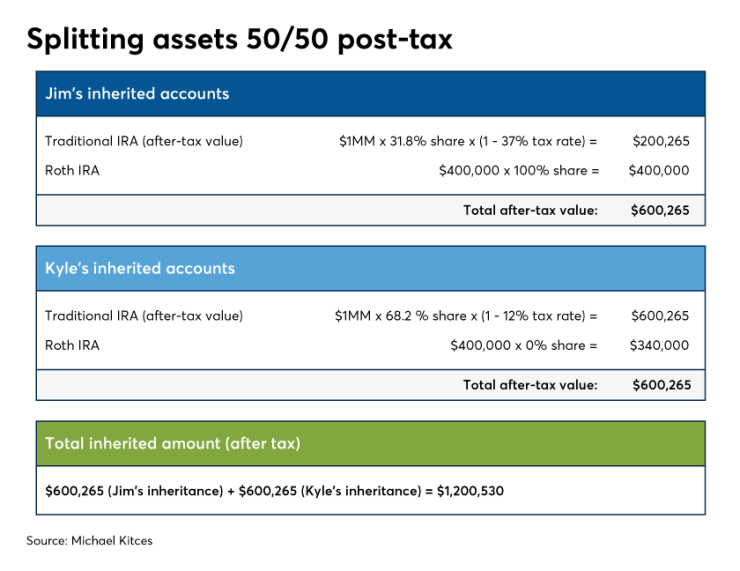

Example 4: Selina, 75, is considering revising her beneficiary designations in light of the Secure Act’s changes. She has a $1 million traditional IRA and a $400,000 Roth IRA, both of which are currently left equally to her two children, Jim and Kyle.

Jim is a successful business owner and is consistently in the top 37% bracket. Kyle, on the other hand, earns a more modest living and is typically in the 12% bracket. If Selina were to die without changing her beneficiary forms, a very simplified analysis of the after-tax value her children would receive upon her passing might look something like this:

The total after-tax value of the inherited accounts combined is $515,000 (Jim’s accounts) + $640,000 (Kyle’s accounts) = $1,155,000.

Suppose, however, that Selina decides to consider the difference in tax situations between her two children when designating her beneficiaries.

For instance, if Selina left 68.2% of her traditional IRA to Kyle and 31.8% to Jim, but all her Roth IRA to Jim, the cumulative after-tax value of Selina’s inherited accounts would be increased to $1.2 million as follows:

Thus, the total after-tax value of the accounts here is $600,265 (Jim’s accounts) + $600,265 (Kyle’s account) = $1,200,530.

Accordingly, by altering her beneficiary designations as outlined above, Selina was able to increase the total after-tax value of her legacy.

Even though splitting assets equally among children may sound like the most equitable strategy, leaving heirs with very different nominal dollar amounts to equalize their after-tax values when there are different account types can increase the total wealth they inherit.

Advisors may also determine that trusts or other legal instruments are preferred to effect a similar, and perhaps even more after-tax-equal, distribution of assets upon the account owners’ passing.

For example, 100% of pretax retirement accounts can be left to beneficiaries in low tax brackets, 100% of Roth IRAs can be left to beneficiaries in high tax brackets, and taxable assets can be left to a trust that contains provisions requiring the trustee to use trust assets to equalize the after-tax inheritance of all beneficiaries.

On the other hand, while there is no question that a willingness to treat beneficiaries differently based on their own income tax situations can result in a greater cumulative transfer of after-tax wealth, there are downsides to this approach that must also be considered.

One is the potential for beneficiaries to feel slighted — even when the account owner’s decisions actually result in such beneficiaries benefiting on an after-tax basis, since not all beneficiaries recognize how to adjust the relative value of their inheritance for the tax brackets of the other heirs.

To minimize this risk, advisors can encourage retirement account owners choosing to treat beneficiaries unequally to discuss such plans during life, so as to avoid any hard feelings after their death. Advisors can do this by helping facilitate such discussions, which should emphasize that differences in inheritances are not indicative of different levels of love or affection, but are simply being done

Another downside is that it can add a significant amount of complexity to an estate plan. For instance, beneficiaries’ income tax situations may change, requiring beneficiary forms and other legal documents to be updated to maintain the after-tax parity of inheritances. Given concerns like these, many retirement account owners will avoid unequal inheritances, even when it may be financially advantageous.

Finally, it should be noted that the Secure Act did not make provision for treating beneficiaries in different income tax brackets unequally in order to maximize the after-tax value of a legacy. It did, however, compress the time such beneficiaries have to distribute such assets, as well as increase the likelihood of large distributions during a beneficiary’s highest-earning years. Thus, the potential benefit that can be achieved by using such an approach has never been more valuable.

Spousal bypass

Another strategy that advisors can use, specifically with married retirement account owners, is to leave some or all of the first-to-die spouse’s pretax retirement accounts directly to the couple’s ultimate beneficiaries, deliberately bypassing the surviving spouse.

Thus, when the first spouse dies the portion of the account that skips the surviving spouse — who may very well have retirement assets of their own — will be inherited by the non-eligible designated beneficiary, at which point a 10-year clock to deplete the account begins. And when the second spouse dies — potentially years after the first spouse’s death — the surviving spouse’s own retirement assets (plus any portion of the first-to-die spouse’s account inherited by the surviving spouse will be inherited subsequently by the non-eligible designated beneficiary, establishing a second 10-year clock to deplete the second account inherited from the surviving spouse.

By using this approach the couple can give their beneficiaries as many as 20 years — provided by the 10 years following the death of each parent — over which to spread cumulative inherited retirement account distributions. This may be accomplished by either updating beneficiary designations to move up contingent beneficiaries as the primary beneficiary, or through the use of disclaimer planning.

Example No. 5: Oswald and Vicki are married retirement account owners who have built up a sizable nest egg. Each partner has been named the other’s primary beneficiary, and their two children as equal contingent beneficiaries. Between each spouse’s own retirement funds and the couple’s combined taxable assets, the surviving spouse will have more than enough assets to support living expenses throughout the balance of his or her retirement years.

Given these facts, the couple may wish to revise their beneficiary designations and name their two children as each of their primary beneficiaries. Alternatively, the survivor can just plan to execute a disclaimer upon the death of the first-to-die. By doing so they will provide their children with two separate 10-year periods to distribute the couple’s combined retirement assets.

The ultimate benefit provided by such a strategy won’t be known right away, as it ultimately depends on how long the surviving spouse lives after the death of the first spouse.

For instance, if Oswald dies in 2020 and leaves his retirement account assets directly to his two children, but Vicki passes away the following year, the change in beneficiary designations will have only bought the couple’s children one additional year over which to distribute their cumulative inheritance — as going forward the beneficiaries will still have to distribute most of both inheritances over the same overlapping time window.

By contrast, if Vicki survives Oswald by 10 or more calendar years, the move will have allowed the couple’s children to spread their cumulative inherited retirement assets over 20 years instead of just 10.

When contemplating this approach though, strong consideration should be given to both the retirement account owners’ tax rate and the beneficiaries’ tax rates. If, for example, the beneficiaries’ tax rates are higher than that of the retirement-account-owning couple, then to maximize the long-term after-tax value of the accounts it will often make more sense for the couple to continue to leave their retirement accounts to each other at the first death.

This strategy is most effective in situations where the size of the retirement accounts to bequeath is large, and the beneficiaries’ tax rates are low — and thus at risk to be driven up materially by a large retirement account inheritance.

Partial Roth conversions

Another straightforward way to remove the impact of higher taxes for beneficiaries is to simply eliminate the tax burden for them altogether via

Of course this strategy will generally only make sense in situations where the tax rate

Having said that, when it comes to tax planning with retirement accounts one key objective is to get distributions out of pretax accounts at the lowest possible rate. In the past such distributions could be spread over the lifetime of the owner, as well as the life expectancy of their non-eligible designated beneficiary at the time of their death. Going forward, however, the same distributions must be distributed over only the owner’s lifetime, plus just 10 years.

Compressing the maximum potential distribution schedule from the owner’s lifetime to just 10 years has the potential to force dollars out of the beneficiary’s inherited retirement accounts at higher tax rates. Logically then, this increases the chances that a beneficiary’s tax rate on distributions will be higher than that of the original retirement account owner, making Roth conversions during the lifetime of an account owner more valuable to a beneficiary in a high-income tax bracket.

That said, as noted earlier, it may take a very sizable retirement account — or a beneficiary with especially low tax rates prone to being increased — given the bracket-smoothing possible simply by stretching out over the available 11 years.

In certain cases, children may even wish to gift non-qualified dollars upstream to parents in order to help pay for the tax liability on converted amounts that they expect to receive upon the retirement account owner’s death. But just because benefits increase doesn’t mean account owners should view Roth conversions as a stretch-loss panacea.

In analyzing potential convert-for-beneficiaries scenarios, owners should first be sure

Life insurance trade-in

Roth conversions are one way to completely remove the impact of taxes on inherited retirement account distributions. But another way to do so involves trading in the retirement account for some other asset, such as life insurance.

For the many retirees who plan to use most of their retirement funds during their lifetimes, this generally is not a viable approach. But for account owners who expect not to need some or all of the savings they’ve accumulated in retirement accounts, it merits a look.

Whether life insurance as a net-after-tax-wealth transfer option makes sense or not depends on a variety of factors, including the retirement account owner’s age, health, the projected rate of return on such assets if they remain invested in a retirement account, and the aforementioned potential need to use the funds to meet living expenses.

Of course the after-tax amount of any pretax distribution from a retirement account used to pay a life insurance premium could instead be used to pay the tax bill on a conversion of other monies in the pretax retirement account. Thus, any discussion or analysis of the potential benefits of replacing a pretax retirement account with life insurance for heirs should also include a fair comparison with the potential benefits of a Roth conversion.

The primary advantage some forms of life insurance offer over Roth conversions is that the insurance can provide a guaranteed amount at death. Roth assets, on the other hand, offer a big edge to the beneficiary after they actually inherit, as they will have access to what could amount to several years of tax-free income.

Notably, while the death benefit of a life insurance policy is income-tax free to a beneficiary, interest, dividends and capital gains begin to be taxable on such amounts beginning on Day One. By contrast, not only is the value of a Roth account generally 100% tax- and penalty-free to a beneficiary at the time of inheritance, the beneficiary will have at least an additional 10 years to allow such assets to continue compounding tax-free.

Charitable remainder trusts

For retirement account owners who still want their beneficiaries to stretch distributions, there may still be a way — sort of — via a charitable remainder trust, or CRT. Though such trusts don’t allow the stretch to be preserved, in many situations they can be designed to replicate several of its biggest benefits, including tax-deferral and a lifetime income stream.

A CRT is an irrevocable trust treated as a charitable entity. As such, when the trust is named as the beneficiary of a retirement account, the entire inherited retirement account can be distributed to the trust without any tax liability at the time of distribution. Furthermore, once inside the trust, future income, interest and capital gains earned on those dollars remain tax-deferred, at least until ultimately distributed to CRT beneficiaries.

Notably, as distributions occur from the CRT to its lifetime beneficiaries, the income tax consequences pass along as well, with heirs being required to report all the CRT distributions that passed from the IRA into the CRT as ordinary income when received by the beneficiary.

In practice, once the inherited retirement funds are inside the CRT they are distributed to beneficiaries in amounts and terms specified by the trust. Such distributions are limited per IRS rules, however, and must generally be between 5% and 50% of the trust’s assets — with the caveat that the net present value of the trust assets must equal at least 10% of the trust’s initial value upon the trust’s termination.

Furthermore, the trust can be drafted to allow distributions to continue for the life of the beneficiaries, for a term-certain period of no more than 20 years or a combination thereof. At the end of the trust’s term — i.e., at either death of the final income beneficiary or at the end of the specified term, whichever is later — the remaining assets in the trust will pass to a qualified charity.

The sum result of these actions is a tax-deferred account that can create a lifetime stream of income to beneficiaries upon death of the account owner. In other words, it’s pretty close to the stretch. But it’s not without its fair share of drawbacks.

Disregarding any costs or complexity that adding a CRT can create, the faux stretch created by CRTs also comes with two other big drawbacks compared to the real stretch. First, CRTs remove optionality. Whereas the stretch allows a beneficiary to take distributions over their life expectancy but does not stop them from taking distributions sooner if desired/needed, the CRT essentially forces the income stream and removes access to the greater principal amount.

Additionally, whereas upon death of the beneficiary of a retirement account any remaining amounts pass to the next-in-line beneficiary, upon death of the income beneficiary of the CRT the remaining assets pass to charity.

Thus, in the event a CRT beneficiary has an unexpectedly early demise, most or substantially all the inherited retirement account may move from the beneficiary’s family to charity. This risk is often mitigated with life insurance, albeit with its own cost to insure.

Example 6: Chris, the owner of an IRA, has a married daughter with taxable income of $200,000. Chris would like to use some of his IRA money to support his favorite charity, but he would also like to see his IRA benefit his daughter while she is living. Given these goals, it may make sense for Chris to establish a CRT to serve as the beneficiary of his IRA.

Suppose Chris names a charitable remainder unitrust, or CRUT, that will pay his daughter 8% of trust assets annually for her lifetime as the beneficiary of his IRA — as the goal is still to distribute the bulk of the trust to the daughter, not necessarily to take a lower withdrawal rate that sustains the trust and shifts even more of the wealth to the charity’s remainder share. Further imagine that when Chris dies, the value of his IRA is $1.5 million and that after being transferred to the trust, the assets earn 7% annually.

Given these assumptions, Chris’s daughter would begin by receiving $1,500,000 x 8% = $120,000 in the first year, as shown in the chart below. If Chris’s daughter’s IRS-given life expectancy were 79, she would receive a total of $2,837,152 of distributions from the CRUT during her lifetime. Furthermore, upon her death Chris’s chosen charity would receive more than $966,000.

So how does this result compare to Chris simply leaving his IRA outright to his daughter? In this case the CRT could actually be a reasonably compelling option.

Given the assumptions outlined above, if Chris’s daughter lived to age 79, she will have received a total of $2,837,152.45 from the CRT during her lifetime. Using a 7% discount rate, the net present value, or NPV, of those payments would be $1,283,208.77.

By contrast, if Chris’s daughter spread the proceeds of her $1.5 million inherited IRA evenly over the maximum 11 tax years, she would need to distribute $186,948.93 annually. The NPV of those distributions when Chris’s daughter is 79 would be $1,401,869.16.

While this amount is more than the NPV of the CRT distributions over the same time, it’s not the dramatically higher amount one might expect considering the charity will end up with close to $1 million. Plus, these NPVs are gross of taxes, so after considering both the impact of taxes on the distributions received from the IRA and CRT at the time of distribution, and the resulting tax drag that would be created if the distributions were reinvested in a taxable account, the real after-tax value of the distributions to Chris’s daughter in both scenarios would be even closer.

Notably, the requirement of a CRT to designate at least an anticipated 10% of the value of the trust to a charity, and the potential for the charity to receive even more depending on the timing of death, can actually shift more value to the charity than the heirs would have lost by simply spreading over the available 11-year period and letting Uncle Sam take his slice.

This is especially true given the heirs still have to pay taxes on any/all IRA distributions when they come out of the CRT to the beneficiary — as they would have by spreading out with the 10-year rule anyway, but now layering an additional portion that must go the charity at the end as well.

Note that in certain situations, particularly where a smaller retirement account is involved that does not justify the upfront and ongoing costs of a CRT, retirement account owners may wish to explore charitable gift annuities, or CGAs.

Such annuities are contracts whereby, after receiving a sum of money, a charity will provide annuity payments back to the donor/annuitant, and potentially to a joint annuitant as well. The payments can have a similar effect to CRTs by providing a lifetime income stream for beneficiaries. Notably though, CGAs generally will not be issued by a charity, if they issue them at all, unless the annuitant is at least 60 years old. (Some charities impose an even later age.) As such, CGAs are generally not viable strategies to provide for young heirs.

Delayed effective dates

For a select group of retirement account owners there may be an even easier way for advisors to help them preserve the stretch, at least for the next few years.

While the

By moving all retirement funds into a governmental plan or one maintained pursuant to a collectively bargained agreement, account owners can delay the onset of the Secure Act’s 10-year rule for their non-eligible designated beneficiaries for an additional two years.

The good news: This is a super-simple way to save the stretch. The bad news: For it to work, the owner must die before the end of 2021.

Conversation is essential

The Secure Act’s changes to the post-death distribution rules for non-eligible designated beneficiaries will have a dramatic impact on many families. If they have not done so already, advisors should immediately review all clients’ beneficiary designations to see which clients have named individuals or trusts that may be impacted.

Once those individuals have been identified, client contact to explain the changes is essential. Advisors should prioritize outreach to those clients with shorter life expectancies, as well as those whose currently named beneficiaries are most likely to experience dramatic impacts on the after-tax value of their inheritances thanks to the Secure Act’s changes.

Such discussions with clients should focus not only on explaining the relevant portions of the Secure Act, but also on the potential strategies to mitigate those changes’ impact. As can be plainly seen in the discussion above, there is no single, one-size-fits-all strategy.

Thus, perhaps one of the most valuable things an advisor can do right now is to present the various Secure Act–mitigating options to clients and to see if there is a particular option — or set of options — that can best help the client accomplish their goals.

Jeffrey Levine, CPA/PFS, CFP, MSA, a Financial Planning contributing writer, is the lead financial planning nerd at