The Federal Reserve’s efforts this year to boost the economy are costing some wealth managers hundreds of millions of dollars.

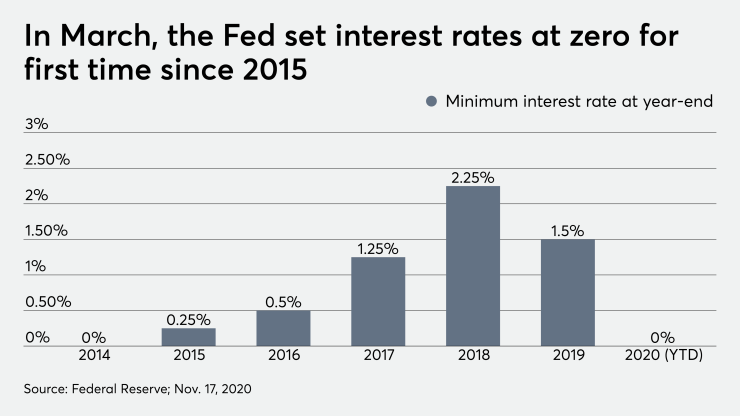

The reason stems from the Fed’s decision to bottom out interest rates earlier this year. That move helped keep markets intact and the economy afloat amid a global pandemic, but it also dealt a blow to financial institutions with revenue tied to these rates. And the timing couldn’t have been worse for some firms that have recently become more reliant on interest income.

Relief on interest rates may not be around the corner. With another coronavirus wave washing over the U.S. and the globe with renewed force, the Fed has

“Low interest rates are going to hurt all kinds of financial companies,” says Patrick Leary, chief market strategist at Incapital, an underwriter and distribution company.

Combined with other hurdles presented by the coronavirus, from shuttered offices to canceled client events, it’s been a challenging year for wealth managers. While some pandemic-related problems can be addressed via technology (think Zoom replacing face-to-face client meetings), the interest rate environment has still taken a toll on revenue. Indeed, third-quarter earnings — from banks, wirehouses, regional and independent broker-dealers and discount brokerages — underlined the industry’s sensitivity to the Fed’s call.

“We are eyes wide open on what's going on in the interest rates in this world,” Morgan Stanley CEO James Gorman said on an earnings call Oct. 15. Morgan Stanley’s net interest revenue

E-Trade, Charles Schwab and other discount brokerages were particularly vulnerable to the interest-rate slash as many of them had

“It took out another revenue stream,” says Pete Crane, whose company, Crane Data, analyzes and publishes money market fund and cash management data. “And of course it took it out at exactly the wrong time.”

The blow to wealth managers’ earnings arrived on the heels of five years of healthy federal fund rates. Money market fund yields topped

But with an economic crisis in tow, the Fed

A mighty headwind

In a press conference earlier this month, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell

Meanwhile, the effects of low rates are showing up on earnings statements.

At Charles Schwab, where net interest made up 55% of its overall revenue in the last quarter, revenue from interest-earning assets

At Raymond James, interest income

Recent history suggests that low-interest rates, once slashed, can stay that way for a long while. Prior to March, the last major reduction in short-term interest rates, aimed at enticing consumers to purchase homes, borrow money and keep spending, took place in

“Looking at examples and the big picture — it doesn't make you feel good,” says Crane.

Despite besting the broader market over the long-term, those at the top have underperformed in the first half of 2020.

For broker-dealers, higher interest rates can be lucrative. When clients leave cash in their accounts, banks and brokerages may invest or loan out that money for a profit. Companies make money off of the difference of that revenue and what they pay clients in interest.

Bank of America, which owns Merrill Lynch, pays the broker-dealer up to $100 per year for each account that sweeps cash into its bank deposit program, according to a

“The deposits provide a stable source of funding,” according to the disclosure, which states that Bank of America uses it to help fund business activities.

In

When margins tighten for brokerages, cash yields shrink for clients, too.

Broker-dealers from

The rates have just been abysmal in a lot of places.

“The rates have just been abysmal in a lot of places,” says Frank Bonanno, managing director of StoneCastle Cash Management, which offers RIAs a FDIC-insured high-yield option for their clients’ cash.

Even so, clients, at least for now, are keeping

“Even if rates overall are glued to zero, as long as there's a yield curve, as long as there's a little difference between short and a little bit longer rates, [brokerages] can make money,” he says.

And while interest rates may be compressing revenues, there are other concerns taking precedence. Coronavirus cases are surging in the U.S., prompting authorities to consider new measures that may lock down large parts of the U.S. economy for the second time this year.

“The traditional metrics of profitability and doing business have gone out the window,” Crane says. “It's just raw survival for entities saying — you know, we'll figure it out after we make it through.”