A conflicted question: What is fiduciary advice?

Northwestern Mutual’s practices raise difficult questions about the nature of retail advice just as wealth management faces greater scrutiny under new rules.

By Tobias Salinger

After 15 years affiliated with Northwestern Mutual, financial advisor Rick Scheeler left the firm this past summer. Nearly a dozen issues had piled up, he says, and they all pointed to one thing: The firm’s policies jeopardized his fiduciary responsibility to his clients.

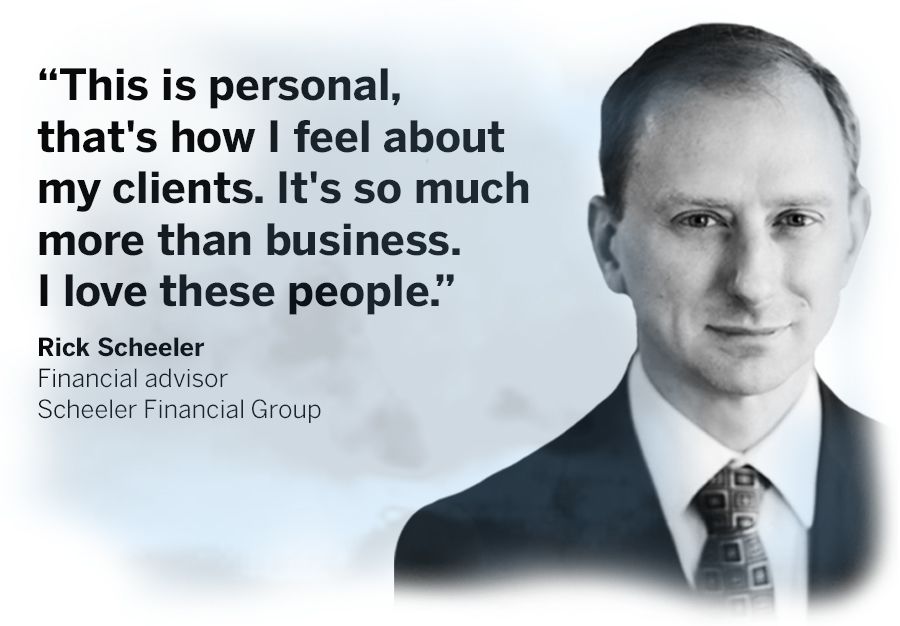

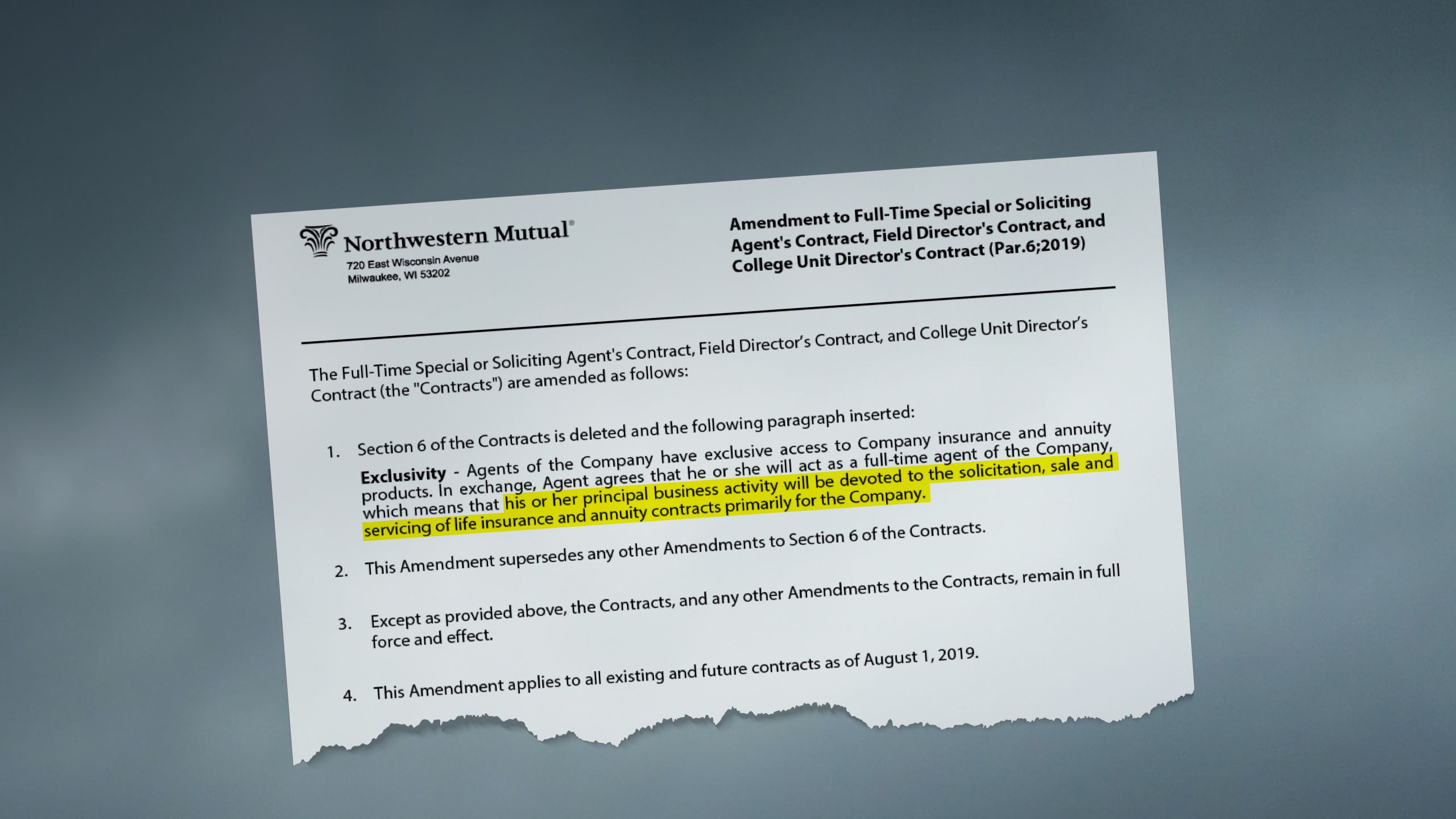

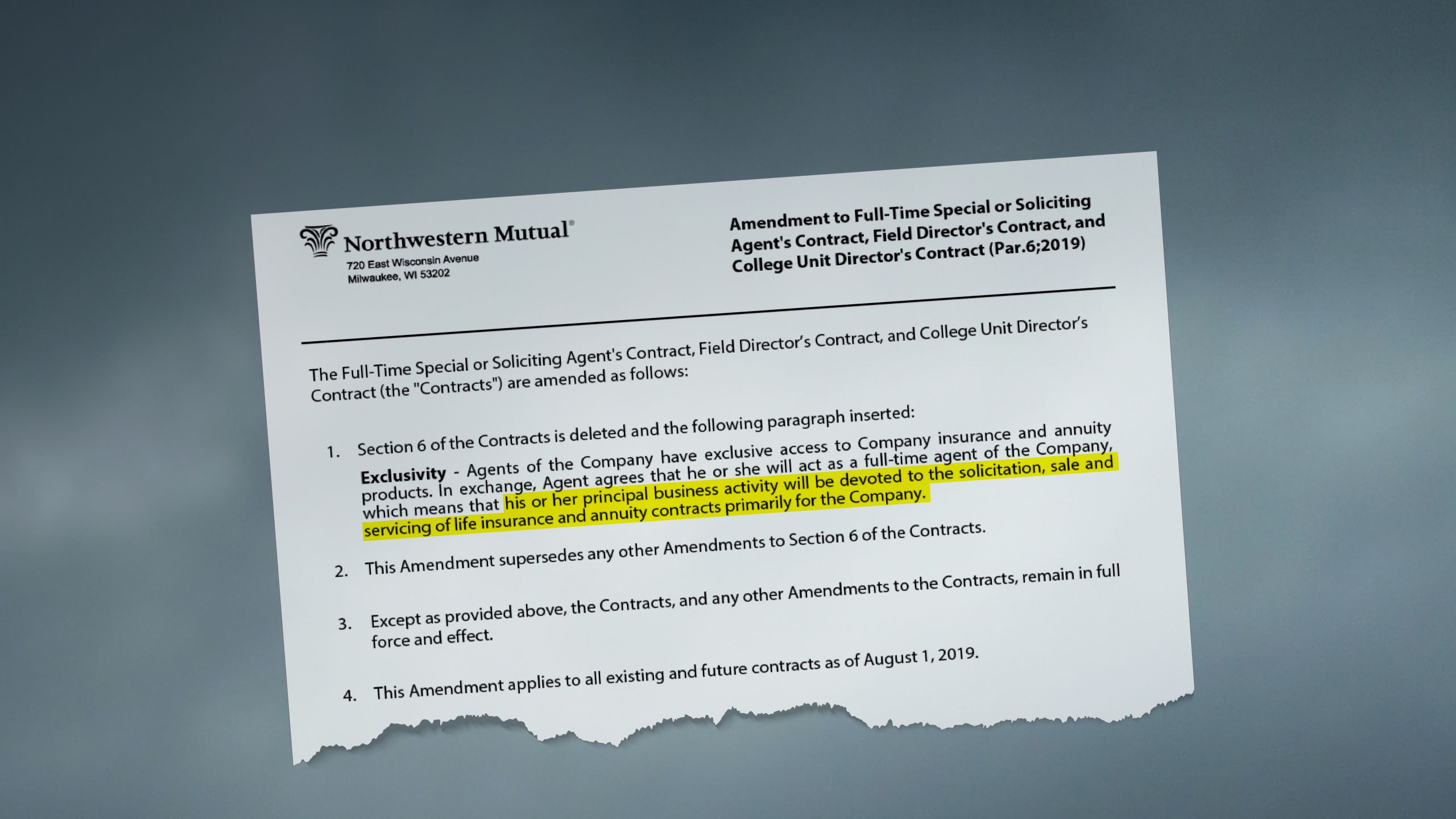

The company closely tied his pay to sales of its insurance. It also tacked on an amendment to one of Scheeler’s contracts which stated that his “principal business activity” was life insurance and annuities that are “primarily” Northwestern products.

“Those documents were creating an inherent conflict of interest,” Scheeler says. “It's a massive insult to what I do. My primary occupation is financial planning and wealth management.”

He and a half dozen former advisors say the firm’s practices impeded their fiduciary planning services to clients. Their accounts — as well as internal company documents obtained by Financial Planning — reveal what they describe as conflicts of interest at Northwestern that raise wider questions about what it means to provide advisory services to retail clients.

Their criticisms and the firm’s rebuttal are ramping up the tensions surrounding a decades-long dialogue about just what it means to provide advice in a client’s best interest. New rules and regulations have tried to clarify advisor obligations toward clients. Some, like the SEC’s Regulation Best Interest — which took effect on June 30 — fall far short in the minds of critics.

Others, like the CFP Board’s new standards, have faced pushback from firms. The board’s standards would require thousands of CFPs with Northwestern and other brokerages to adhere to fiduciary standards in all their financial advice.

Northwestern — and many other brokerages — use proprietary service models that serve as in-house distribution channels for fund or insurance products. These carry their “own kind of conflicts and challenges” beyond the underlying concern that some advisors and firms aren’t really putting clients’ interest first, says Barbara Roper, director of investor protection at the Consumer Federation of America, an investor advocacy group.

The SEC “refuses to use the authority Congress gave it” and is not applying an effective standard of care on brokers and advisors, says Roper. This “has rendered the word ‘fiduciary’ all but meaningless,” she says.

Representatives for the SEC didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A prominent industry player

Northwestern is one of a pioneering group of independent broker-dealers that helped create the wealth management sector in the late 1960s. Today, wealth management annual revenue is more than $1 billion, a portion of its nearly $30 billion in total; it spends tens of millions a year on advertising, often heralding its commitment to planning. The company has filled the airwaves with TV commercials and sponsored major sporting events like March Madness and The Rose Bowl Game.

The firm's wealth management business revolves around rewarding advisors for selling more of what the company refers to as its “core” annuity and insurance products. Along with the pay grid and contract language, some advisors decry a sales-driven culture rewarding insurance production over investment advice. They also say the firm charges exorbitant fees such as a $500 charge to open an advisory account.

A Northwestern executive says its policies don’t hinder fiduciary advice; a spokeswoman said in an email that the firm’s programs fees “evolve” and the price cited by the former advisors is out of date. Additionally, though Financial Planning obtained a 2020 compensation grid showing a payout of at least 85% of revenue for advisors who generate at least $1.16 million, Northwestern says it was only a draft version. Its integrated compensation grid reflects the role played by insurance and investments in providing for financial security, according to the firm. Northwestern also connected Financial Planning with an advisor who says the Milwaukee-based firm has never impeded his recommendations to clients.

To view the chart in higher resolution, click here.

Seven former Northwestern advisors who dropped their affiliation with the firm in the past three years view the situation differently. The comp grid nets higher payouts to advisors based on the combined premiums from sales of the company’s so-called core products. It gives added incentives for Northwestern annuities as well as the firm’s life, disability and long-term care insurance. The grid is fueling advisor moves as part of an accelerating trend, according to IBD recruiter Jon Henschen.

“As advisors mature in their business, they always go more towards wealth management, and the captive insurance BDs just don’t cater to that market as deeply as firmly independent firms do,” Henschen says. “There are a lot of these captive insurance BDs that have CFPs, and they might increasingly see their environment as a conflict of interest.”

Advisor exits

In addition to the grid, Scheeler cited an automatic amendment to advisors’ insurance contracts last August that explained their main business as being “devoted to the solicitation, sale, and servicing of life insurance and annuity contracts primarily for the company.” Higher advisory fees, a fintech boondoggle, and the company’s culture contributed to his decision to leave, he says.

“You're not appreciated as a financial advisor,” Scheeler says. “Even if you've got $2 million in [gross dealer concessions], if you're not selling annuities and insurance, you're not being appreciated. It makes it very hard to be objective, and you don’t even see it while you're there.”

“It’s like a fish that's so used to water,” he added. “I don’t think that the fiduciary responsibility has sunken in at most firms, in [terms of] truly what that means.”

Donovan Sanchez started his career as a Northwestern rep before launching his fee-only practice, Skyview Financial Planning, in 2018. A former teacher who switched careers, Sanchez explained in an article on “The White Coat Investor” blog why he left Northwestern.

In his three-week training, the firm instructed him to compile a list of 200 friends, family members and acquaintances to contact in an effort to make the firm’s “Pacesetter 40” level of 40 policies sold in his first six months.

“I wanted to do financial planning,” Sanchez says. “My advice, if I was going to feed my family, had to lead to some sort of sale.”

“I still really appreciate a lot of the people I met while I was there,” he adds. But “a lot of the advice is going to lead to a product. … Clients just don’t quite understand how the way they're paying their advisor influences those things. They're hoping to get unbiased financial advice.”

For Eric Raether of Canopy Wealth Management, the comp grid was “the final straw” causing him and another ex-Northwestern rep to launch their fee-only RIA in 2018. In hindsight, though, he says the payouts were only one of its shortcomings.

Raether cites a $15 fee for stock and ETF trades at Northwestern even as other firms have been cutting their prices to zero. Northwestern also charged a high program fee for its advisory platform — which meant that the smaller accounts of around $15,000 or less usually wound up in brokerage accounts with shares of mutual funds that come with added load costs, Raether says.

“In retrospect, it seems like compensation was the smallest part of it,” he says. “I appreciate the fact that they did do that because I might not have made the change. Just being able to run our practice and give our clients a better experience has been the biggest thing.”

Raether estimates his RIA’s clients are saving around 15 to 20 basis points on an identical portfolio because of the move. Still, he praises Northwestern’s insurance products, saying many clients have retained them and that he continues working with representatives from the firm.

Northwestern received the highest rating for client satisfaction for individual life products among 24 issuers whose clients participated in J.D. Power’s 2019 survey. The four other advisors who spoke with Financial Planning requested anonymity to do so, citing concerns about litigation or remaining ties to the firm. Their clients also still have Northwestern insurance, the advisors say.

Free to disagree

In response to the advisors’ critiques, Northwestern directed Financial Planning to John Roberts, who oversees about 8,000 registered representatives as the firm’s vice president of distribution performance. It also made advisor Tom Weilert, a partner of Dallas-based WWA Integrated Wealth Strategy Group, available for an interview.

Northwestern increased certain rates of advisor compensation for proprietary sales by “a few” percentage points in 2018, according to Roberts. But it has had its integrated comp grid for around a decade, in which the rates changed slightly each year, he says.

“We approach the market as a holistic financial planning firm. And we believe pretty firmly and in a pretty forthcoming way that integrated planning of investments and insurance products is the path to financial security,” Roberts says. “That integrated grid is another expression from Northwestern Mutual of our proud belief in financial planning. … It's really through the combination of these products that we believe clients are best served.”

The $15 fee on equity and ETF trades is only one “slice of the whole pie” in terms of the company’s value proposition, according to Roberts.

Planning is “absolutely part of our recognition for advisors,” says Roberts, noting the firm’s Pathfinder Award requires management of investment assets and insurance. The insurance and annuities contract, amended last year, is different from the securities agreement. The securities agreement enables independent recommendations of external products and funds, Roberts says.

In terms of the training program, Northwestern instructs its 2,200 to 2,400 prospective reps to approach their personal networks as an exercise to find their respective markets. Roberts also points out that roughly 40% to 45% of the training classes are women, Black people and other minorities.

Weilert, the advisor, started his tenure with Northwestern in 1980, but he says he and his team didn’t branch into investment planning from insurance and estate services until around 2000. WWA has four equity partners leading its ensemble team — which manages about $500 million in client investment assets, $400 million in life insurance policies and $100 million in annuities.

He cites Northwestern’s financial stability and its foundational pledge to work in the best interests of policyholders as two factors in his tenure of four decades with the firm. Weilert has recommended non-Northwestern insurance each year without any pushback from the home office, he says. The practice discusses costs like the trading fees from the beginning.

“We show them the fee structure, and we talk about both the advisory fee and the embedded fee,” he says, acknowledging other advisors opt for more independence. “Reasonable people can have a different approach, and that's OK. The most important thing to do is to educate the client. … We're comparing what they're paying in total compensation to the value we're adding.”

Commercial planning

The debate takes place as Northwestern spends significant ad dollars touting financial advice to clients.

In 2018 and the first half of 2019, the firm spent $96.4 million on advertising, according to information consultancy Kantar. Sponsoring the Rose Bowl reportedly costs an extra $25 million per year, and March Madness is also several millions.

That’s not as large as some other firms. Spending over that span by Nationwide ($199.7 million), Charles Schwab ($209 million) and Wells Fargo ($382.5 million) ran far higher.

Northwestern’s ads make the firm’s planning acumen a major selling point of its campaigns.

“At Northwestern Mutual, our version of financial planning helps you live your dreams today,” the narrator says in one of its ads. The commercial then tells viewers to “find a Northwestern Mutual advisor” as the words “planning,” “insurance” and “investments” appear on the screen.

The ads may also help Northwestern garner more than its share of online snark. T.J. van Gerven, a fee-only CFP, poked fun at the firm by tweeting the meme of “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills” cast member Taylor Armstrong yelling at a smug cat.

“You said this was a top 10 internship! I’m just selling life insurance to friends and family,” the caption says above the picture of an angry, pointing Armstrong. The uncaring white cat Smudge, seated contentedly at a dining table like a monarch, is labeled “NWM manager.”

Industry in conflict

In a 2017 report, the Consumer Federation pointed out how 25 firms, including Northwestern, Wells Fargo, Morgan Stanley, Edward Jones and Schwab, presented representatives in marketing material under titles like financial advisors, planners and wealth managers. Yet when the firms’ trade groups sued the Department of Labor to vacate its fiduciary rule in 2016, they argued that the reps were merely salespeople working on commission.

The SEC’s Reg BI will force some changes upon the industry, such as prohibiting the use of the word “advisor” for a representative providing only brokerage services rather than advisory accounts. Some dually registered firms could still opt to use terms like “financial professional” instead of “advisor.” In addition to requiring new “customer relationship summary” documents, the SEC also worked with the Labor Department to propose a new fiduciary rule last month aligning the agency’s retirement rules with Reg BI.

Northwestern and other brokerage firms that provide advisory services can receive commissions called 12b-1 fees and asset-based fees on the same security. They also receive kickback payments from fund companies called revenue sharing in exchange for a place on the menu of investment recommendations for affiliated advisors.

The arrangements explain why “dual registration exposes fiduciary clients to unique conflicts,” according to a working paper by Northeastern University Professor Nicole Boyson.

Regulators have hardly ignored them. Dual registrant firms have paid more than a half a billion dollars in fines and restitution since 2003 over what the SEC deemed inadequate disclosure of conflicts from 12b-1 fees and revenue sharing, according to Boyson’s research.

|

|

Many financial advisors — let alone ordinary investors — make their decisions in the marketplace without being aware of serious conflicts of interest affecting the majority of retail clients, Northeastern University Professor Nicole Boyson says in a Financial Planning Podcast. |

After nearly 100 cases last year, many firms are trying to avoid the extra 12b-1 marketing and distribution fees or rebating them to clients, Boyson says. Her paper and other academic research show evidence that products sold by the same firm that manufacture them underperform external funds, she said in an email.

“Many of the firms that have affiliated products state that they prefer these products and perform less due diligence on their own products,” Boyson said. “Fiduciaries are supposed to avoid putting their own financial interests ahead of their clients.”

Other experts cut Northwestern a little slack, even as they express reservations about industry regulations. Michael Kitces — a Financial Planning contributing writer and co-founder of XY Planning Network, which unsuccessfully sued the SEC to block Reg BI — has spoken at Northwestern conferences. He also works with dual registered firms through his online payment company AdvicePay.

Northwestern is “leading the charge on the future of the fiduciary insurance channel, which is kind of a cool thing because none of the other companies seem to be doing it,” Kitces says. “They seem pretty interested in trying to figure out how to actually be fiduciary advisors in the future. And that's a hell of a thing for a company that's been manufacturing and selling insurance products for 150 years.”

Predictions for the future

Sanchez, the former Northwestern advisor who launched his own fee-only firm, predicts commissions and even the 1% AUM fee will one day be industry relics. And he believes his ex-employer has an opportunity to do great financial planning for investors.

“They've got the infrastructure there,” Sanchez says, noting other brokerage firms with large advisory platforms and dual-registered reps are facing some of the same challenges. “Both those models will have to be significantly altered, or they're going to have to go away.”

Raether’s RIA has some $600 million in AUM. He compares advisor exits from Northwestern in the past two years to earlier departures after a 2007 Supreme Court ruling that ended non-fiduciary advisory services and Northwestern’s addition of a non-solicitation agreement to reps’ contracts in 2012.

He has strived “to keep it amicable” with Northwestern in case one of his clients could benefit from one of its whole life, LTC or disability policies.

“From that standpoint, Northwestern Mutual is a good company,” Raether says. “Trying to marry this idea of a fiduciary advisor who’s also selling proprietary products — that's a conflict of interest.”

Edited by Andrew Welsch, designed by Neesha Haughton