Perhaps the present moment is not the best time to ask clients how much risk they can handle.

“Everybody is more aggressive when the market is doing well and when it turns, everybody turns into a conservative,” says John Masegian, CEO of Pruneyard Financial, an investment advisory firm in Campbell, California.

The extent to which it has turned can be measured by the Cboe Volatility Index, which gauges the market’s anticipation of future volatility. A higher VIX reading means greater expected frequency and magnitude of up and down price movements. The low value for the VIX was around 11 until March 17 — when it rose to more than 82 with the escalation of the coronavirus pandemic.

There’s a reason that Wall Street calls VIX the “fear index.”

Masegian and other advisors cite the current market tumble as one of the reasons they use low-volatility ETFs as a core equity holding for their clients in good times and bad

Ryan Marshall, a partner at ELA Financial Group in Wyckoff, New Jersey, sees great value in using these products for retired clients. Particularly for those with about 50% of assets in equities, he says, “most of that will go into low-volatility funds.”

Marshall uses such funds for risk-averse non-retirees as well. The firm uses Riskalyze software to share “the potential downside” of low-volatility — and other approaches — with them.

One of Marshall’s pro-low-volatility arguments is that the S&P 500 is market-capitalization weighted. “Some of the top names in the S&P 500 in 1999 were AOL and Lucent,” he says, adding that AIG was a major S&P 500 component in 2008.

“When I say that, they really understand it and get it,” Marshall says.

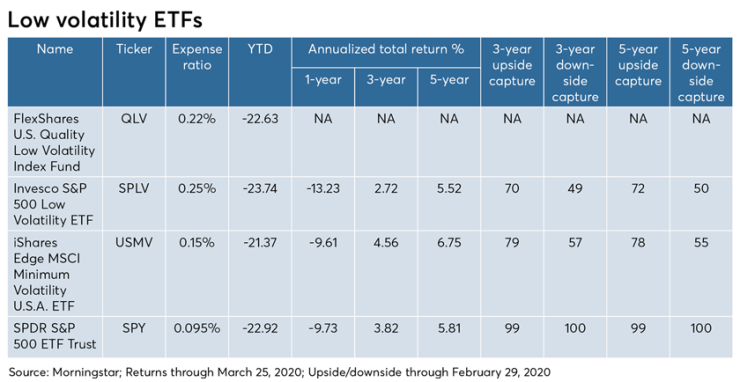

His favored vehicle is iShares Edge MSCI Minimum Volatility U.S.A. ETF (USMV). Marshall likes that the fund’s design requires “looking at how the underlying holdings correlate with one another,” as opposed to some low-volatility portfolios that have “an overweight to utilities.”

Masegian says low-volatility holdings don’t do badly in rising markets. “We noted that [they] performed quite well during the recovery period 2010 and on,” he says. Pruneyard has used low volatility products since 2015, “And we’ve been very pleased with the results.”

Initially, Masegian’s firm used the oldest such ETF, Invesco S&P 500 Low Volatility (SPLV), which tracks the 100 stocks in the S&P 500 with the lowest volatility over the past 12-month period.

Although Masegian says “we have no complaints about that methodology per se. It’s a reasonable approach to the problem.” But he also notes that low volatility in the past is no guarantee of low volatility in the future, citing energy stocks as an example.

More recently, Pruneyard switched to FlexShares US Quality Low Volatility Index Fund (QLV), an ETF that was launched in July 2019. Masegian says he likes that the ETF uses “additional factors” such as the health of the company, cash flow and debt to select holdings.

Marketing scheme?

But not all advisors are sold on the idea of low volatility funds. Kevin Sullivan, a financial planner at Rockbridge Investment Management in Syracuse, New York, sees these portfolios as “marketing schemes.”

The only thing that’s going to lower volatility in a portfolio is the amount of fixed income you have.

“Nobody would ever think of marketing a high-volatility ETF, but a low volatility sounds appealing,” he says. Rather, Sullivan takes what he calls a traditional asset allocation approach to risk. “The only thing that’s going to lower volatility in a portfolio is the amount of fixed income you have,” he says.

While Alex Bryan, Morningstar’s director of passive strategies for North America, says “There’s some truth to” Sullivan’s view, he goes on to say that low-volatility funds “tend to lag during market rallies, but they more than make up for that by offering better downside protection.”

What about a hybrid approach? Bryan opines that “It can be a benefit if you combine low volatility with some other factors like value or quality.But when you add them in, you also tend to increase risk a little bit.”