Recent changes in the tax law have raised some interesting questions about compensation, and clients are taking notice.

Specifically, what are the implications on deductions if an advisor charges fees or commissions?

Internal Revenue Code Section 212 permits individuals to deduct any expenses associated with the production of income or the management of such property — including fees for investment advice. However, the new tax codes eliminated the ability of individuals to deduct Section 212 expenses.

The legislation also made payments to advisors compensated via commission payable on a pre-tax basis, while advisory fees paid directly to advisors became ineligible for deduction. It’s a rich irony, given the current legislative and regulatory push toward more fee-based advice.

While some savings strategies remain, advisors need to account for this shift, while still emphasizing the very real tax benefits that exist for some clients — particularly those in higher tax brackets.

A long-recognized principle of tax law holds that income should be reduced by any expenses that were necessary to produce it. Thus, businesses only pay taxes on their net income after expenses under

This means that investment management fees

On the other hand, not all fees to advisors are tax-deductible under IRC Section 212. Given deductions are permitted only for expenses directly associated with the production of income, planning fees on their own are not deductible. Further, while tax planning advice and tax preparation fees are deductible, the preparation of estate planning documents

The caveat to deducting Section 212 expenses came in how they were deducted. Specifically,

In practice, this meant that Section 212 expenses, including fees for advisors, were only deductible to the extent they exceeded 2% of AGI and the individual

As a part of the recent tax law change, Congress substantially increased the standard deduction and curtailed a number of itemized expenses, including the

Technically, Section 67 expenses are just suspended for eight years (from 2018 through the end of 2025, when the law sunsets) under the new

There are some exceptions. Under

Example 1. Charlie’s $250,000 traditional IRA is subject to a 1.2% annual advisory fee. His advisor can either bill the IRA directly to pay the $3,000 fee, or draw on Charlie’s separate/outside taxable account — which

Yet given the recent changes, if Charlie pays the $3,000 advisory fee from his outside account, it will be an entirely after-tax payment, as no portion of the Section 212 expense will be deductible in 2018 and beyond. By contrast, if he pays the fee from his traditional IRA, his $250,000 taxable-in-the-future account will be reduced to $247,000, implicitly reducing his future taxable income by $3,000 and saving $750 in future taxes, assuming a 25% tax rate.

Simply put, the virtue of allowing the traditional IRA to pay its own way and cover its traditional advisory fees directly from the account is the ability to pay with pre-tax dollars. Viewed another way, if Charlie had waited to spend the $3,000 from the IRA in the future, he would have owed $750 in taxes and only been able to spend $2,250. By paying the advisory fee directly from the IRA, he satisfied the entire $3,000 bill with only $2,250 of after-tax dollars.

What’s more, IRAs aren’t the only type of investment vehicle capable of implicitly paying their own expenses on a pre-tax basis.

COMMISSIONS

The

Example 2. Jessica invests $1 million into a $99 million mutual fund that invests in large-cap stocks, in which she now owns 1% of the total $100 million of value. Over the next year, the fund generates a 2.5% dividend from its underlying stock holdings, for a total of $2.5 million in dividends, which at the end of the year will be distributed to shareholders — of which Jessica will receive $25,000 as the holder of 1% of the outstanding mutual fund shares.

However, the direct-to-consumer mutual fund has an internal expense ratio of 0.60%, which amounts to $600,000 in fees. Accordingly, of the $2.5 million of accumulated dividends in the fund, $600,000 will be used to pay the expenses of the fund, and only the remaining $1.9 million will be distributed to shareholders, leaving Jessica with a dividend distribution of $19,000. Stated more simply, Jessica’s net distribution is 2.5% (dividend) - 0.6% (expense ratio) = 1.9% (net dividend that is taxable).

The end result is that while Jessica’s investments produced $25,000 of actual dividend income, the fund distributed only $19,000, as the rest was used to pay the expenses of the fund. This means Jessica only pays taxes on the net $19,000 of income. Viewed another way, Jessica managed to pay the entire $6,000 expense ratio with pre-tax dollars — literally $6,000 of dividend income that she was never taxed on.

That’s significant, because if Jessica had simply owned those same $1 million of stocks directly, earned the same $25,000 of dividends herself and paid a $6,000 management fee to an advisor to manage the same portfolio, she would have had to pay taxes on all $25,000 of dividends. In other words, the mutual fund or ETF structure actually turned non-deductible investment management fees into pre-tax payments via the expense ratio of the fund.

In addition, a commission payment to a broker who sells a mutual fund is treated as a distribution charge of the fund — i.e., an expense of the fund itself, to sell its shares to investors — that is included in the expense ratio. This means a mutual fund commission is effectively treated as a pre-tax expense for the investor.

Example 2a. Assume instead that Jessica purchased the mutual fund investment through her broker, who recommended a C-share class with an expense ratio of 1.6%, including an additional 1%/year trail expense that would be paid to her broker for the upfront and ongoing service.

In this case, the total expenses of her $1 million investment into the fund will be 1.6%, or $16,000, which will be subtracted from her $25,000 share of the dividend income. As a result, her end-of-year dividend distribution will be only $9,000, effectively allowing her to avoid ever paying income taxes on the $16,000 of dividends that were used to pay the fund’s expenses, including compensation to the broker.

Ironically, Jessica’s broker is paid a 1%/year fee entirely before tax, even though if Jessica hired an RIA to manage the portfolio directly — with the same investment strategy, the same portfolio and the same 1% fee — the RIA’s 1%/year fee would no longer be deductible. This occurs as long as the fund has any level of income to distribute, which may be dividends as shown in the earlier example, or interest or capital gains.

Granted, it does not appear that the new, less favorable treatment for advisory fees compared to commissions was directly intended, nor did it have any relationship to the

DEDUCTION STRATEGIES

Given the current regulatory environment, with both the Labor Department and various states

Of course, not all advisory fees were actually deductible in the past — due both to the 2%-of-AGI threshold for miscellaneous itemized deductions and the impact of AMT — and advisory fees are still implicitly deductible if paid directly from a pre-tax retirement account. Nonetheless, for a wide swath of clients, investment management fees that were previously paid pre-tax will no longer be pre-tax if actually paid as a fee rather than a commission.

Given the apparently unintended deduction distinction between fees and commissions, it’s entirely possible that subsequent legislation from Congress will reinstate the deduction. After all, investment interest expenses remain deductible under

Unfortunately, one of the most straightforward ways to at least partially preserve favorable tax treatment of advisory fees — to simply add them to the basis of the investment, akin to how transaction costs like trading charges can be added to basis — is not permitted. Under

This means that advisory fees may be deducted or not, but cannot be capitalized by adding them to basis as a means to reduce capital gains taxes in the future.

Nonetheless, there are at least a few options available to advisors — particularly those who charge now-less-favorable advisory fees — who want to maximize the favorable tax treatment of their costs to clients, including:

– Switching from fees to commissions

– Converting from separately managed accounts to pooled investment vehicles

– Allocating fees to pre-tax accounts (e.g., IRAs) where feasible

MAKING THE SWITCH

For the past decade, advisors from all channels

Of course, once a broker

Given these regulatory constraints, it may not often be feasible for dual-registered or hybrid advisors to switch their current clients from advisory fee accounts back to commission-based accounts, especially for those who have left the broker-dealer world entirely and are solely independent RIAs with no access to commission-based products.

Still, for those with a hybrid or dual-registered status, there is at least some appeal now to shift tax-sensitive clients into C-share commission-based funds, rather than using institutional share classes or ETFs in an advisory account.

It’s also important to note that many broker-dealers have a lower payout on mutual funds than what an advisor keeps on their RIA advisory fees, and it’s not always possible to find a mutual fund that is exactly 1% more expensive solely to convert the advisor’s compensation from an advisory fee to a trail commission. Furthermore, some clients may already have embedded capital gains in their current investments and not be interested in switching. That’s saying nothing of the risk that Congress might reinstate the investment advisory fee deduction in the future, thereby introducing additional costs for clients who want to switch back.

Nonetheless, for dual-registered or hybrid advisors who do have a choice about whether to receive compensation from clients via advisory fees versus commissions, there is some incentive for tax-sensitive clients to use commission-based trail products — at least in taxable accounts where the distinction matters; as previously noted, even traditional advisory fees within an IRA are being paid from pre-tax funds anyway.

THE POOLING STRATEGY

For very large advisory firms, another option to consider is to turn their investment strategies for clients into a pooled mutual fund or ETF, such that clients of the firm will be invested not via separate individual accounts that the firm manages, but instead into a single or series of mutual funds created by the firm. The firm’s 1% advisory fee may not be deductible, but its 1% investment management fee to operate the mutual fund would be.

Unfortunately, this approach also comes with significant challenges. Apart from overcoming the client’s potential objection to holding what appears to just be one mutual fund, the firm loses its ability to customize client portfolios beyond standardized models used for each of their new mutual funds. It also necessitates a purely model-based implementation of the firm’s investment strategies, given it’s no longer feasible to implement

Yet for the largest independent advisory firms, creating a mutual fund or ETF version of their investment offering — if only to be made available for the subset of clients who are most tax-sensitive, and have large holdings in taxable accounts where the difference in tax treatment matters — may be appealing.

THE IRA STRATEGY

For advisors who don’t want to or can’t feasibly revert clients to commission-based accounts or launch their own proprietary funds, the most straightforward way to handle the loss of tax deductibility for advisor fees is simply to have them be payed from eligible retirement accounts.

This means that advisory firms will need to bill each account for its pro-rata share of the total advisory fees, given IRAs should only pay advisory fees

It’s worth recognizing though that the IRA would have grown tax-deferred in the long run, while a taxable brokerage account is subject to ongoing taxation on interest, dividends and capital gains. This means that eventually, giving up tax-deferred growth in the IRA on the advisory fee may cost more than trying to preserve the pre-tax treatment of the fee in the first place.

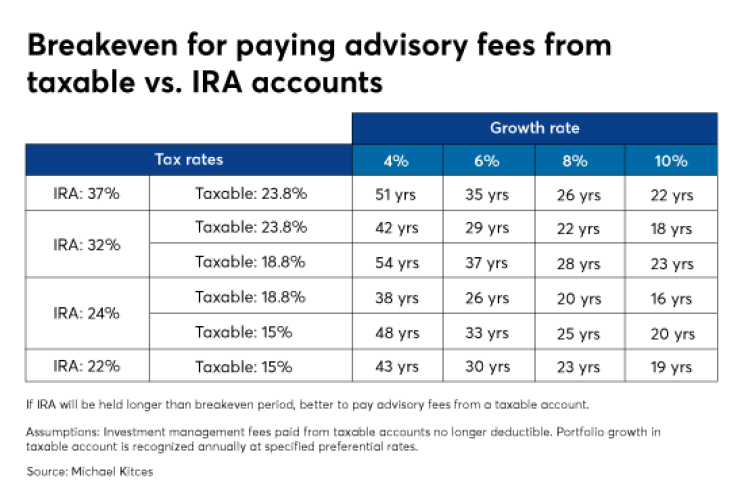

The chart below shows how many years an IRA would have to grow on a tax-deferred basis, without being liquidated, to overcome the loss of the tax deduction that comes from paying the advisory fee on a non-deductible basis.

As the results reveal, at modest growth rates it is a multi-decade time horizon, at best, to recover the lost tax value of paying for an advisory fee with pre-tax dollars. And the higher the income level of the client, the more valuable it is to pay the advisory fee from the IRA, as the implicit value of the tax deduction becomes even higher. Nonetheless, at least some clients — especially those at lower income levels, with more optimistic growth rates, and very long time horizons — may at least consider paying advisory fees with outside dollars and simply eschewing the tax benefits of paying directly from the IRA.

In the end, when the

But for more affluent clients in higher tax brackets, the ability to deduct advisory fees can save one-quarter to one-third of the total fee of the advisor, or even more for those in high-tax-rate states, which is a non-trivial total cost savings. Hopefully, Congress will intervene and restore the tax parity between advisors who are paid via commission, versus those who are paid advisory fees. For the time being though, the disparity remains, which ironically has made tax planning for advisory fees itself a compelling tax planning strategy for advisors.

So what do you think? Are you maximizing billing traditional IRA advisory fees directly to those accounts after the TCJA? Will larger firms creating proprietary mutual funds or ETFs to preserve pre-tax treatment for clients? Will Congress ultimately intervene and restore parity between commission- and fee-based compensation models for advisors? Please share your thoughts in the comments below.