With the reintroduction of comprehensive Social Security legislation this week, experts say the willingness of Congress to act may finally be starting to meet the urgency of the task at hand.

If lawmakers continue to do nothing significant in the way of Social Security bills, the benefits of tens of millions of Americans will

A pair of competing bills are offering contrasting approaches to ensure the solvency of the program and retirees’ full benefits. Republican Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah has attracted moderate Democrats to the Time to Rescue United States’ Trusts

The vast majority of people of all political backgrounds “feel leaders in Washington do not understand how hard it is for Americans to save for retirement,” Larson said at a press conference. “People's skepticism is validated by Congressional inaction,” he said.

Larson’s bill, which he’s introduced in every session of Congress since 2014, received co-sponsorships from nearly 200 Democratic lawmakers and more than 100 advocacy

Representatives for AARP didn’t respond to a request for the group’s position on the legislation. Representatives for Romney’s office and that of Rep. Mike Gallagher, a Wisconsin Republican who introduced a House version of the Trust Act, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Rhian Horgan, the CEO of retirement planning app Silvur, said the provisions in

Horgan “would be shocked” if Congress didn’t come together with a long-term solution for the program, whether through adjusting the limits on taxable wages or by delaying the full retirement age, or some combination, she said.

“This is the foundation of retirement security in America,” she said. “This is not just about a safety net, this is about a system that millions of Americans have paid into.”

Horgan and Shai Akabas, director of economic policy for the Bipartisan Policy Center think tank, expressed some cautious optimism for Congressional action. While the chances for passing a comprehensive bill this year are “very slim,” there are more lawmakers engaging in behind-the-scenes bipartisan talks and an “increasing recognition among members on both sides that Congress needs to get serious about solving this problem,” Akabas said.

The think tank’s PAC issued a statement supporting Romney’s bill, which has drawn Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Mark Warner of Virginia, and independent Sen. Angus King of Maine as co-sponsors. As for Larson’s bill, Akabas said a larger group than the wealthiest 2% of workers ought to pay higher tax rates, and the legislation should hike benefits for retirees who need them most rather than across the board.

“The Larson bill uses most of the revenue that it collects to pay for an expansion of benefits when the system is obviously underfunded to begin with,” Akabas said. “Social Security is a very broad-based system. We are going to need a solution that calls on most, if not all, Americans to contribute more into that system and then make difficult decisions about where benefits growth needs to be scaled back, particularly among higher-income beneficiaries.”

Still, he said it’s good to see a comprehensive proposal like the Social Security 2100 Act. At the event on Capitol Hill for the re-introduction, Larson noted that 10,000 baby boomers become eligible for Social Security every day and that Millennials “will need Social Security more than any generation before.” With slim majorities in Congress and a Democrat in the White House in President Biden, Larson said the bill is more likely to pass.

“What's different is we have a person on Pennsylvania Avenue who knows and understands that Social Security is a sacred trust,” he said. “Some say our plates are too full here in Congress to take up Social Security, but frankly it's the plates of working Americans that are full. Our job is to ease their concerns by strengthening the program that over 65 million Americans rely on.”

Carrying out that duty has remained elusive since Congress last expanded benefits 50 years ago and in the 38 years since the last major legislation, Larson acknowledged. Despite the demographic trends of the wave of baby boomers retiring and a smaller base of workers entering the system due to lower fertility rates in the past several decades, the financing shortfall adds up to just 1% of GDP,

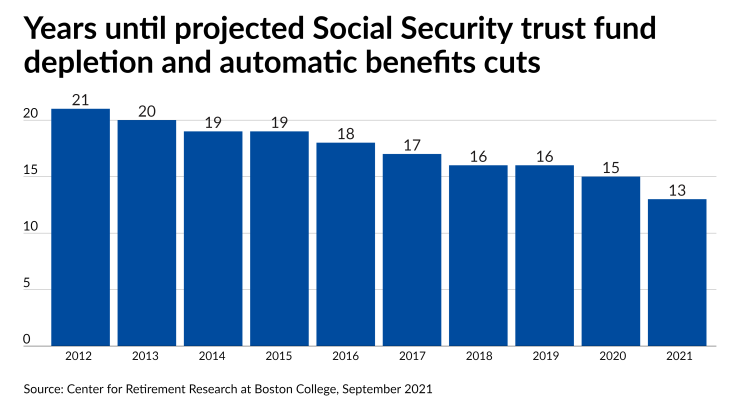

“The changes required to fix the system are well within the bounds of fluctuations in spending on other programs in the past,” Director Alicia Munnell wrote in the report last month. “Moreover, action needs to be taken before the trust fund is depleted in 2034 to avoid a precipitous cut in benefits. Americans support this program; their representatives should fix its finances.”