Years ago, one of Jeffrey Tomaneng’s clients came into his office and made some casually scathing anti-Semitic remarks.

“Somehow he started talking about Jews — they lie, they cheat. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I stopped him, let him know that I was offended, told him I was going to make a request to have his account reassigned and asked him to leave my office,” says Tomaneng, who is currently an adviser at Lincoln Investment in Waltham, Massachusetts.

His boss at the time wasn’t happy, because Tomaneng was sending away assets under management. “I didn’t care at the time and I would do the same thing today,” he says.

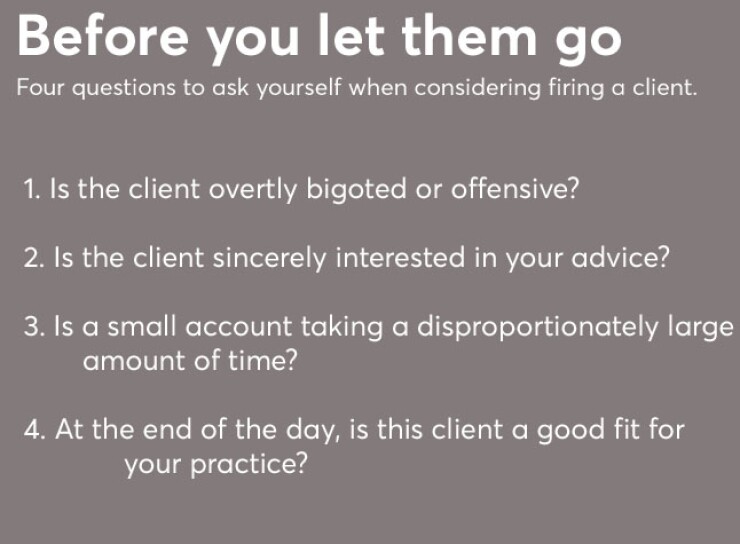

Tomaneng’s decision to fire that client was an easy one. But many other situations involving difficult clients are murkier. When, if ever, should you ask a client to leave your practice?

Is the client sincerely interested in your advice?

If a client doesn’t really care what you say, the relationship probably won’t work. Another Tomaneng client had $100,000 in a 403(b) through her job as a schoolteacher. Unfortunately, she also had a massive shopping problem.

“Her home was like something out of the television show ‘Hoarders,’” Tomaneng says. “She was spending more than she made each month, had a loan balance against her retirement and was asking her landlord to write a delinquency notice every month so she could increase her loan balance beyond the usual maximum-through-hardship distributions.”

Tomaneng explained that the client needed to dial back her spending and replenish her savings, but his advice fell on deaf ears. “She wasn’t interested in helping herself. We were just processing her paperwork,” he says. Tomaneng removed himself from the account.

Is a small account taking too much time?

Robert Schmansky, president of Clear Financial Advisors in Livonia, Michigan, recalls a separated couple who needed a disproportionate amount of time-intensive management.

The husband was the first problem. “In the first quarter of 2015, his investments were down along with the market, and I started getting angry emails, always within a day or two from the end of the month,” Schmansky says. Although Schmansky sends monthly emails and quarterly market updates, the clients weren’t satisfied. “The[y] demanded to know at the end of each month why their accounts weren't growing,” he says.

“Clients have to be nice. That's critical. The rest I can try to work with.”

The client wouldn’t respond to Schmansky’s attempts to set up an appointment to talk, so Schmansky disengaged — which brought even angrier email. “He was mean. I’ve had clients be very upset about misinterpretations of things, but they’ve been willing to talk and listen,” Schmansky says. “Clients have to be nice. That's critical. The rest I can try to work with.”

Nearly two-thirds of advisors surveyed this month said that internal training programs or workshops were offered by their firms.

Virtually every major firm on Wall Street has joined the push into private markets, with many trying to get in early on the biggest "next big thing" to hit financial services since the exchange-traded fund.

Traci Parks has been a copy editor at American Banker since 2023. She's worked at Scholastic National Partnerships and many fashion magazines, including V Magazine where she was also a contributing writer. As a playwright, her work has been produced in New York, Seattle and Los Angeles.

After Schmansky let the husband go, the wife started sending him similarly aggressive emails, and he fired her. Total revenue from both accounts? “Less than $10,” Schmansky says.

At the end of the day, is this client a good fit for your practice?

Whether a client is bigoted, won’t take advice or is hard to manage, the most serious problems boil down to one thing: The client and the planner aren’t a good match. “We just had to resign an account because we weren’t the right fit for that client,” says Michael Baker, partner and co-founder at Vertex Capital Advisors in Charlotte, North Carolina. “Over a series of conversations, it became clear that their expectation for us wasn’t realistic. The parameters they were choosing to judge our value were unacceptable. They were never going to be happy.”

In that situation, Baker says, it’s better to cut bait quickly. “If I get to the point where I don’t feel I can serve a client as effectively as they need to be served or realize that there is nothing we can do that will satisfy them, I will give them a letter of resignation,” he says.

“You’re going to have difficult conversations in this business. It’s part of the job.”

Not that firing the client is ever easy, he adds. Sometimes a client’s departure hurts financially, and it nearly always wounds professional pride. Because planners want to serve and please their clients, severing the relationship can feel like a failure.

Get past that, Baker advises. “You’re going to have difficult conversations in this business. It’s part of the job,” he says.