A single word change has upended wealth management.

By substituting an “and” for an “or” in a footnote last week, the SEC watered down the meaning of investment advisors’ fiduciary duty to clients. The change prompted sharp criticism from multiple quarters, including the commission’s own investor advocate, and left industry insiders bewildered.

"It guts the RIA industry,” says Brian Hamburger, founder of MarketCounsel, a regulatory compliance consulting firm. “RIAs are not fiduciaries anymore.”

As part of the Regulation Best Interest rules package, the SEC revised its interpretation of an RIA’s fiduciary duty. Previously, advisors had to seek to avoid conflicts of interest and make a full disclosure of all material conflicts of interest. The SEC changed the “and” to an “or.”

That alteration “weakens the existing fiduciary standard by suggesting that liability for nearly all conflicts can be avoided through disclosure,” SEC Investor Advocate Rick Fleming

“I do not believe this is what an investor would reasonably expect from a fiduciary, nor does it align with the ways that real-world investment advisors tend to view (and describe) their fiduciary obligation,” Fleming said.

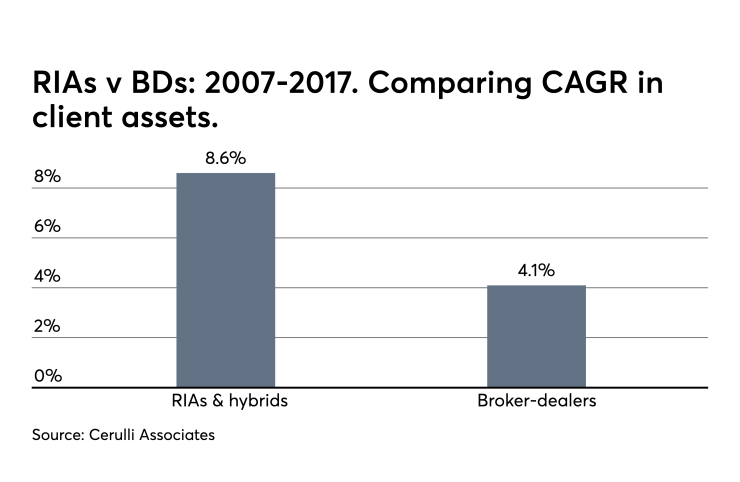

The broader implications could be far-reaching. If, over time, the fiduciary downgrade erodes the quality of service provided by the RIA industry, as numerous experts predict, it could depress the value of all RIAs. Client assets for RIAs, including hybrids, grew at a compound annual rate of 8.6% from 2007 to 2017 compared to 4.1% for broker-dealers, including independent broker-dealers and insurance advisors, according to Cerulli. Many industry insiders credit this fast growth as stemming from the high legal standard the commission has required of RIAs. But the SEC’s revision could undermine independent advisors’ advantage in the marketplace.

The commission has rendered the definition of fiduciary "meaningless," says Barbara Roper, director of investor protection at the Consumer Federation of America.

In his own statement, the one

Chairman Jay Clayton, who along with two other commissioners voted for the change, asserts otherwise, describing the new guidance as "reaffirming — and in some instances clarifying — the fiduciary duty investment advisers owe to their clients."

“This rulemaking package,” Clayton says in

Indeed,

The inescapable problem with disclosure,

"We all know consumers read glossy sales literature and not disclosure documents that are dozens and hundreds of pages long with dense language written by lawyers," says Ric Edelman, co-founder of Edelman Financial Engines, one of the largest RIAs in the country with about $200 billion in client assets under management. "Clients accept the verbal assertions of their advisor rather than reading prospectuses. It is therefore essential that the advisors be required to behave as fiduciaries, rather than disclose away behaviors that are not in the best interests of their clients."

Edelman calls the commission’s revision Orwellian. "This is doublespeak and this is very worrisome that the government has overtly created a confusing landscape that will only serve to harm investors," he says.

In response, the SEC provided the following statement: "Our rules and interpretations are designed to enhance the quality and transparency of retail investors’ relationships with investment advisors and broker-dealers, and preserve access (in terms of choice and cost) to a variety of types of advice relationships and investment products. ... Our fiduciary interpretation in no way weakens the existing fiduciary duty; rather, it reflects how the commission and its staff have applied and enforced the law in this area.” The commission did not elaborate when asked how a change that makes the mitigation of conflicts of interest voluntary either preserves or strengthens RIAs' fiduciary duty.

LEMONS

By opening the door for RIAs to legally introduce conflicts of interest into their practices, the whole RIA space runs the risk of falling prey to the Market for Lemons economic phenomenon, says Benjamin Edwards, associate professor of law at the University of Nevada’s law school in Las Vegas.

Market for Lemons is a foundational work of

"As this happens, it drives down the quality of the goods in that marketplace to the point where all you have left is lemons," Edwards says. "If people can't distinguish between good advice and bad advice, you will gradually see bad advice take over the market."

The SEC's position on this subject springs from a fundamental misunderstanding of the limits of disclosure's effectiveness, Edwards says. "The SEC tends to fetishize disclosure because it's so important for public companies, [but] nothing like that can operate in the financial advisor space — it's a misplaced disclosure fetish."

When it comes to public company regulation — a core responsibility of the commission — large, well-funded industry players such as mutual fund companies, hedge funds and research giants like Morningstar minutely dissect disclosures to derive valuable insights. Many investors then buy products and services, often guided by insights gleaned from those disclosures, Edwards says.

But wealth management is a different beast. Disclosures given to clients are unlikely to face the level of scrutiny and expertise conducted by research firms and mutual fund companies. When the SEC leaves the analysis to retail investors — who, even if they had the time to read through volumes of disclosures, lack the background to understand them — the value of any transparency evaporates, Edwards says.

The SEC has been blinkered before about the impacts of its rulemaking, says Dave Yeske, co-founder of RIA Yeske Buie in San Francisco.

WHEN THE FPA TOOK ON THE SEC

That's why

The SEC move was well-intended, he thinks, surmising that commissioners thought it would reduce brokers' tendency to churn client accounts for higher commissions.

But they overlooked different ways the exception enabled brokers to self-deal in those accounts, according to Yeske, such as selling clients in-house products for high commissions. A federal appeals court overturned the SEC’s exemption for brokers in 2007.

Edwards says he expects to see legal challenges to the SEC's new regulation, in much the same way that the brokerage industry killed the Department of Labor's fiduciary rule by challenging it in court.

The SEC has already faced a bevy of criticism.

Yeske wonders, "Who the hell ever thought we'd ever see the Investment Advisers Act under such assault?"