The Securities and Exchange Commission wants to give advisors and investors a little more time for quality reading.

The average length of shareholder reports submitted to the SEC in 2020 was 134 pages, but some reports stretched well over 1,000 pages. That's roughly as long as Homer's Iliad and Odyssey combined or three of J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter books, Commissioner Caroline Crenshaw said during an agency hearing on Oct. 26.

"Depending on your frame of reference, before finishing some open-end fund shareholder reports, you can have either traveled from Troy to Ithaca, or have made it through the escape of the Prisoner of Azkaban," she said.

Crenshaw's remarks came just before she and fellow commissioners voted unanimously in favor of a

The rule will require fund managers to use their annual and semiannual reports to convey core information that Wall Street's regulator deems most useful to individual investors and advisors. That includes data on a fund's expenses, past performance and holdings. Fund managers, for instance, will have to list the expenses that would come with a hypothetical $10,000 investment in their funds.

The rule will also encourage the use of graphs and other features to make the presentations appealing. And it will require the use of text coding to make online versions of the documents searchable by keywords.

Financial professionals and investors who want information that now can bulk out shareholder reports to unmanageable lengths could still find that documentation on funds' websites. They'd have to request to see it, and couldn't be charged for that privilege. The SEC rule would also require all fees charged for funds to be reported in a consistent way and would bar funds from advertising themselves as "no fee" if there's a chance such expenses could arise in the future.

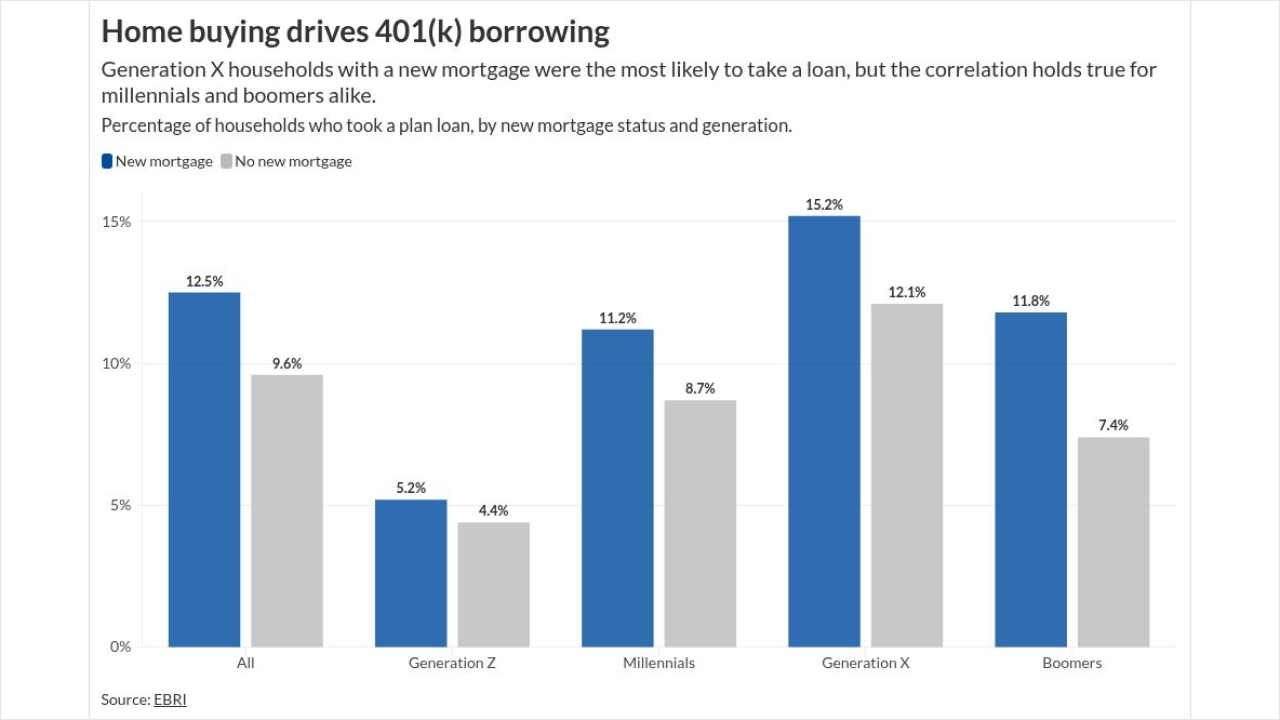

Commissioner Jaime Lizarraga said during the SEC's meeting that a rule of this sort is needed in an age when so many investors are called on, either through working with a financial advisor or participating in a 401(k) plan, to choose among a wide variety of investment funds. Typically, mutual funds are actively overseen by fund managers and are traded only once a day. Exchange-traded funds, by contrast, trade throughout the day on stock exchanges and are often tied to the performance of an external investment index like the S&P 500.

"Depending on their investment portfolios, some investors may need to review multiple fund reports," Lizaragga said. "Having to process complex, lengthy and technical disclosures where the relevant investor-useful information is difficult to discern is burdensome under any circumstances, but particularly so for families operating under the short-term pressures that household budgets often demand."

Although the rule was passed unanimously by the commission, it didn't escape criticism. Commissioner Hester Peirce said during the meeting that she wished the SEC had gone further. She conceded that it's not easy deciding what information should be included in a simplified shareholder report and what excluded.

"While in general, this rule should improve the investor experience, several policy choices cut against that conclusion," Pierce said.

Among other things, Pierce questioned the SEC's policy on multi-class funds, which can have holdings in various asset classes such as stocks, bonds or cash. Pierce noted that the new rule would require investors in these funds to receive information only about the particular asset class they are invested in. But why, she asked, not let them know of opportunities to invest in other assets in the same fund?

"Shareholder reports showing the range of share class options would allow fund investors to see cheaper class options available to them," Pierce said.

Eric Pan, the president and CEO of the Investment Company Institute, which represents regulated investment funds, welcomed the rule.

"Though we continue to review the rule, we know that presenting key information in a digestible, layered manner will increase investor understanding,"he said.

The new rule officially takes effect in 60 days but will then be phased in over 18 months to give fund managers time to come into compliance.