For the past several decades, RIAs have differentiated themselves from competing broker-dealers by the best interest fiduciary standard. Broker-dealers were always subject to a lower suitability standard consistent with the sales-centric role they were created to fulfill.

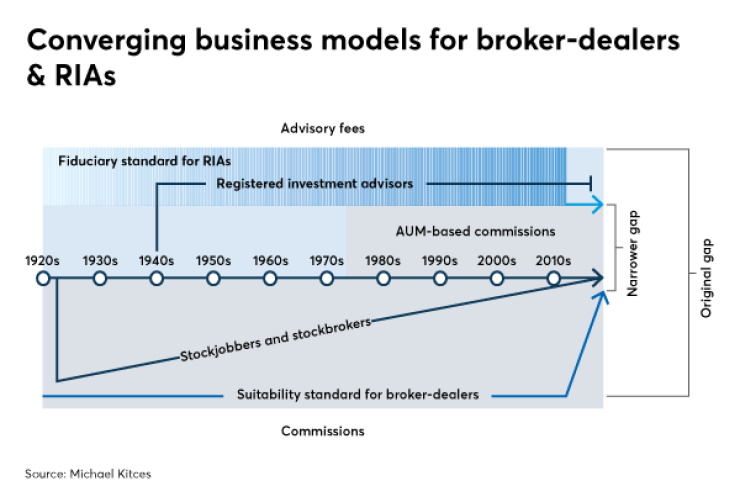

But over the past several decades, as technology has commoditized the core functionality of broker-dealers, the RIA and broker-dealer channels have undergone a great convergence, to the point that a consumer may pay 1% per year for ongoing advice in the form of a fee-based wrap account, a C-share mutual fund trail or an advisory fee, and not even make a distinction between the choices.

This convergence in turn puts pressure on RIAs to justify not only their fees, but their value on a more holistic level. Ironically, the fiduciary standard is becoming a zero-sum game, whereby the more advocates push for higher standards, the less likely those elevated standards will be an effective differentiator. That’s why I argue that the best path forward for most advisors will be to differentiate on their services and what they actually do for clients, rather than the standard of conduct they hold themselves to.

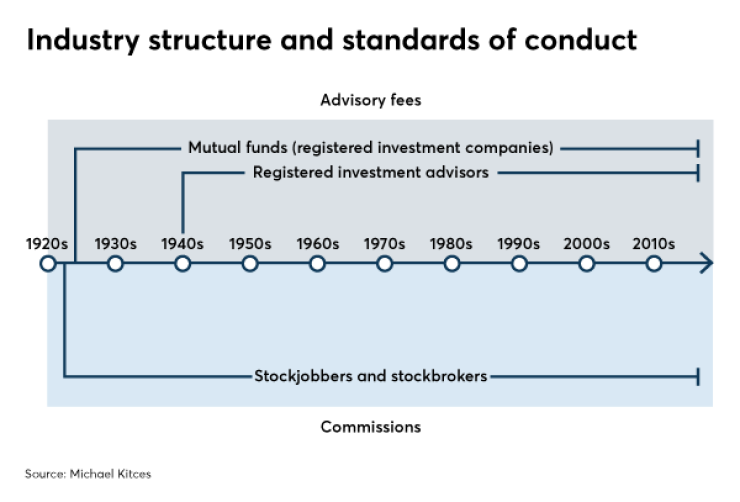

When the modern structure of financial services regulation was created in the early 1900s, broker-dealers and investment advisors were in substantively different businesses. Advisors supervised and managed investment accounts for clients, while broker-dealers and their stockjobbers, i.e., stockbrokers, were primarily involved in the capital formation and capital markets processes of facilitating the issuance of stocks and bonds and their subsequent trading.

Accordingly, these groups had different business models. Broker-dealers were paid by the transaction, whereas advisors were paid for advice. They also had different standards of conduct: suitability for broker-dealer sales activity, and fiduciary for investment-advisor advice services.

But over the years, the evolution of the marketplace has driven multiple shifts in the services provided by broker-dealers.

In the ‘70s, the deregulation of fixed trading commissions for broker-dealers led to the rise of discount brokerage firms like Schwab and Ameritrade which, through their newfangled computing technologies, drove the traditional human stockbroker out of business. This development also forced broker-dealers to shift toward selling mutual funds instead — supported by the

By the ‘90s, with the rise of the internet and the emergence of online brokerage firms, a shift away from broker-sold mutual funds got underway as consumers rightly began to ask, “Why should I pay a broker for a mutual fund that I can buy myself online without a commission?” This in turn led the brokerage industry to wrap accounts, and a request to the SEC to create an

The end result is that today, an advisor typically charges 1% of a client’s investment account balances to provide upfront and ongoing planning advice; holds themselves out as a financial advisor and/or consultant; and there’s hardly a distinction made between whether it’s a 1% wrap account, a 1% trail on a C-share mutual fund or a 1% advisory fee. From the consumer perspective it’s

Yet technically, a 1% wrap account or a 1% trail on a C-share mutual fund is simply an alternative, leveled form of commission for product sales or ongoing transactions, and only the latter is actually a fee for advice. That is important because again, the industry applies different standards of conduct to different channels, recognizing the gulf between a suitability standard and a fiduciary one.

This means in essence that the industry’s regulations weren’t created for the convergence of industry channels that has occurred. The standards were written for a world where broker-dealers sold securities, and investment advisors sold advice.

This led to a

REGULATION BEST INTEREST

Given the convergence of broker-dealer and RIA business models, the SEC’s Regulation Best Interest, or Reg BI, was created to close the gap in standards of conduct between broker-dealers and RIAs.

Reg BI specifically stipulates that:

“A broker, dealer, or a natural person who is an associated person of a broker or dealer, when making a recommendation of any securities transaction or investment strategy involving securities (including account recommendations) to a retail customer, shall act in the best interest of the retail customer at the time the recommendation is made, without placing the financial or other interest of the broker, dealer, or natural person who is an associated person of a broker or dealer making the recommendation ahead of the interest of the retail customer.”

Notably, a key aspect of Reg BI is that it applies only at the time the recommendation is made, and not to the overall broker-dealer business model or its relationship to the client, recognizing that broker-dealers still fulfill many non-advice roles in capital markets — e.g., principal trading and more generally facilitating the distribution of securities to investors.

Creating a

- Disclosure: Providing certain prescribed disclosure before or at the time of recommendation about the recommendation and the relationship between the retail customer and the broker-dealer;

- Care: Exercising reasonable diligence, care and skill in making the recommendation;

- Conflict of interest: Establishing, maintaining and enforcing policies and procedures reasonably designed to address conflicts of interest;

- Compliance: Establishing, maintaining and enforcing policies and procedures reasonably designed to achieve compliance with Reg BI.

The end result of these changes is that, notwithstanding industry criticism to the contrary, Reg BI really does lift the standard of conduct for brokers from where it was — if not to a full fiduciary standard.

WHAT ABOUT RIAS?

In addition to lifting the standard of conduct for broker-dealers, the SEC also

Nonetheless, RIAs do have a fiduciary obligation to “eliminate or at least expose,” i.e., disclose, their conflicts of interest, stemming from the famous

Notably though, one of the key distinctions of a traditional fiduciary standard is that conflicts of interest don’t just have to be disclosed and exposed. They are expected to be eliminated or mitigated, and only the unavoidable conflicts of interest are to be disclosed.

By contrast, the SEC’s explicit emphasis on RIAs having an obligation to “eliminate or disclose,” rather than an obligation to eliminate and disclose where avoidance/elimination isn’t feasible, is a less stringent version of the fiduciary obligation for RIAs.

Accordingly, some —

The reality of course is that an RIA’s fiduciary duty was always very disclosure-based. This is why, ironically, the

Indeed, a wide range of conflicts of interest are already permitted for RIAs, as long as they’re disclosed in Form ADV. These can range from charging differential fees for different asset classes — even when the RIA has discretion over the allocation, meaning the RIA effectively has discretion over its own fees — to earning commissions through related businesses or entities.

This is why, several years ago, CNBC highlighted a list of the

While many RIAs highlight that they don’t receive any investment commissions as RIA fiduciaries, technically this isn’t because the RIA fiduciary rules prohibit them from doing so. Rather, it’s because they don’t have a broker-dealer license to earn that commission in the first place. If they did, earning advisory fees and brokerage commissions for product sales would remain entirely permissible under an RIA’s fiduciary duty.

That is why so many hybrid advisors are dual-registered with a broker-dealer and an RIA. In fact, Reg BI guidance explicitly notes that in the case of dual registrants, the RIA’s fiduciary duty extends only to the actual advisory accounts which he/she manages, while Reg BI — and more generally, the broker hat of the dual registrant — applies to the rest of the commission-based transactions that may occur.

In practice this means the SEC’s interpretation of an RIA’s fiduciary duty may be less of a weakening and more of a formal recognition of what was already a pretty weak disclosure standard. Many RIAs may have chosen to adhere to a higher version of the fiduciary standard, where conflicts of interest were actively mitigated and not merely just disclosed, but that was a choice of the individual RIA and not necessarily a reflection of the actual fiduciary requirement that applied.

Nonetheless, just as the business models of broker-dealers and RIAs have converged — albeit not to the point of being identical, but at least very similar — so too have the standards of conduct for broker-dealers and RIAs now converged, with broker-dealers being lifted up and RIA fiduciary standards at least being clarified at the lower end of the fiduciary range.

FIDUCIARY DIFFERENTIATION, R.I.P.?

While Reg BI does lift the standard of conduct applicable to broker-dealers, it also will likely spell the end of fiduciary differentiation for RIAs.

That’s because broker-dealers will now be permitted to market that they, too, operate in the best interest of their customers when making recommendations, as that is literally their new legal standard of conduct.

In fact, under the

“When we provide you with a recommendation, we have to act in your best interest and not put our interest ahead of yours. At the same time, the way we make money creates some conflicts with your interests. You should understand and ask us about these conflicts because they can affect the recommendations we provide you.”

By contrast, RIAs will be required to state:

“When we act as your investment adviser, we have to act in your best interest and not put our interest ahead of yours. At the same time, the way we make money creates some conflicts with your interests. You should understand and ask us about these conflicts because they can affect the investment advice we provide you.”

Notably, the wording between the two about the standard of conduct and relationship to the client is almost the same. And that’s the point. In the case of broker-dealers, the best-interest standard is technically limited to just when providing a recommendation, whereas the best-interest standard for investment advisors applies to the entire relationship.

Still, the wording of both makes clear that each group is subject to a best interest standard. The SEC didn’t even include the word “fiduciary” in the description of an RIA’s standard of conduct, noting that:

“… some commenters, and results from investor studies and surveys, indicated that many did not understand the meaning of ‘fiduciary’ or had never heard of the word. Accordingly, the modified standard of conduct disclosure both eliminates technical words such as ‘fiduciary,’ and describes the standards of conduct of broker-dealers, investment advisers, or dual registrants using similar terminology in a plain-English manner.”

Beyond the remarkably similar wording on Form CRS itself, the

Accordingly, when in the summer of 2020 major broker-dealers start launching their new, “We are obligated to act in your best interest” advertising campaigns, how will fiduciary RIAs differentiate themselves?

WHAT’S TO COME

One tactic is to highlight how broker-dealers only have the obligation at the time of recommendation, versus RIAs who have the obligation with respect to the entire advisory relationship. In other words, the differentiator might not be, “We’re fiduciaries subject to a best interests standard,” but rather, “We’re fiduciaries at all times.”

Another option would be to differentiate through professional designations, particularly ones like CFP certification that carry their own fiduciary standard. In fact,

This means voluntarily getting CFP certification and subjecting oneself to the CFP Board’s fiduciary standard effectively becomes another version of a fiduciary-at-all-times differentiator. It’s also one to which the advisor

Fiduciary pioneer Don Trone and others have suggested that perhaps the leaders of the advisor community will seek out and adopt a new term of differentiation to describe their scope and standard that leaves fiduciary behind, such as “stewardship.”

Similarly, stewards have a sense of purpose and character, while fiduciaries just have to meet the letter of the law. Stewards hold higher expectations of competency, cannot turn a blind eye even on behalf of other non-clients and — similar to at least what fiduciary represented in the past — is a higher aspirational standard that not everyone can or would choose to reach.

On the other hand, one of the reasons why fiduciary in particular was so effective as a voluntary standard was that it also is a formal legal term, and not one that could be thrown around lightly by firms without risk of having the actual legal duty become attached. By contrast, stewardship may have aspirational meaning and historical significance, but no real grounding in law.

Perhaps the most straightforward path for advisory firms is just to differentiate on their services and their value, rather than the standard of conduct by which they operate. The fact that RIAs so commonly

Accordingly, the demise of fiduciary differentiation may only do more to steer advisory firms toward

Ultimately, it’s not hard to see why the broker-dealer community has in the end

The irony is that the different best interest standards between broker-dealers and RIAs

In response, a number of states, from Nevada to New Jersey to Massachusetts, have begun to propose or implement their own rules, subjecting any and all advisors in their states to a fiduciary duty, regardless of whether they present themselves as RIAs or broker-dealers.

Yet even if the future of a fiduciary duty for advice takes the form of a state obligation, the endpoint remains the same. As fiduciary advocates win the battle to lift the standards of conduct on broker-dealers providing advice, the very nature of differentiating as a fiduciary is no longer as relevant as it once was. And while Reg BI isn’t mandating a full fiduciary duty, it is still close enough to undermine any perceived differentiation by consumers in the standards of conduct between broker-dealers and RIAs.

Stated more simply, advisors may be winning the fiduciary battle, but without