It was July 2018 and Michael Henley and his $1 billion team had a decision to make — one with a big price tag attached.

They had bolted from Merrill Lynch to go independent, seeking what hundreds of breakaway advisors have gained in recent years: more control over the client experience and more say in what tools and software would be at their fingertips.

“The financial planning software at Merrill Lynch was limited,” Henley recalls. “They had to make it workable for 15,000 advisors, who range from 25 to 75 years old. When you are making a platform that fits everyone, it’s hard to make it customizable for the individual advisor.”

Like other breakaways, Henley’s team faced a slew of decisions: What financial planning software to use? Where to set up shop? What to call themselves?

On the CRM front they initially went with the familiar: Salesforce, which they had used at Merrill Lynch and knew to have “a lot of firepower.” But a couple weeks after establishing their own firm, Henley’s team found they weren’t using nearly as many of Salesforce’s capabilities as they anticipated. At roughly $20,000 per year, it was a pricey subscription for Henley’s eight-person RIA.

“It was like buying a Ferrari just to commute to work. It didn’t make sense,” he says.

So, exercising their business owners’ prerogative, the team switched course and went with Redtail, which cost them $99 per month for 15 users.

“At the wirehouse you are forced to use the tools you are given — whether you use 10% of it or 90% of it, it makes no difference to them,” Henley says. “As an RIA, you have the flexibility to ask yourself: ‘What makes the most sense for my clients?’ Being able to make those decisions is the reason you see this paradigm shift to independence.”

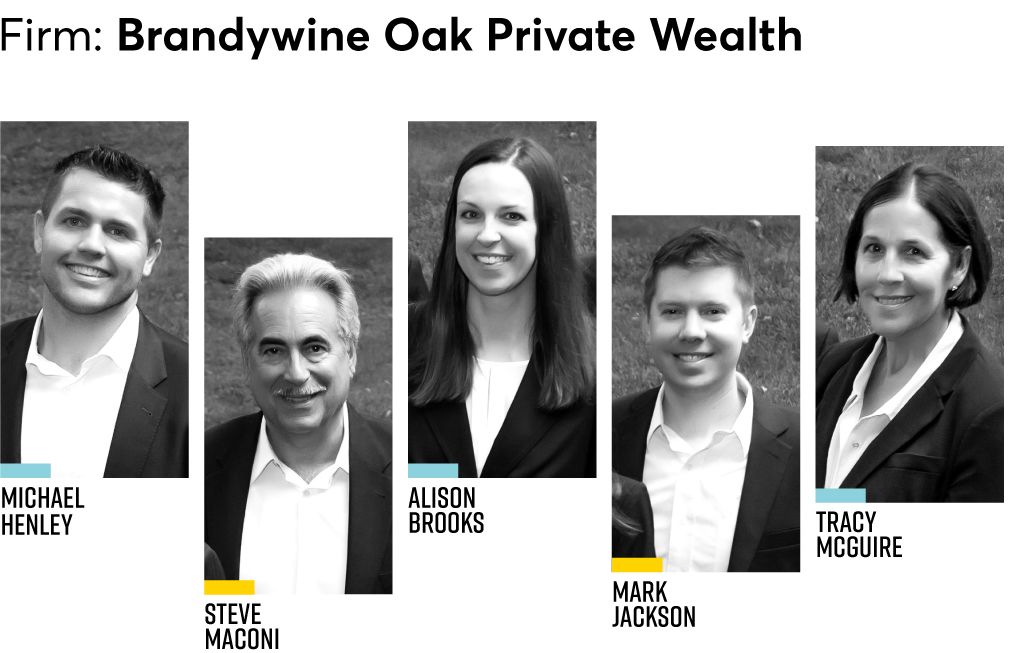

And quite a shift it has been: Since 2014, more than 800 advisors have gone independent, aligning themselves with independent broker-dealers or as RIAs, according to hiring announcements and BrokerCheck data analyzed by Financial Planning. Those advisors managed more than $140 billion in combined client assets, according to career moves confirmed by Financial Planning with advisors and hiring firms.

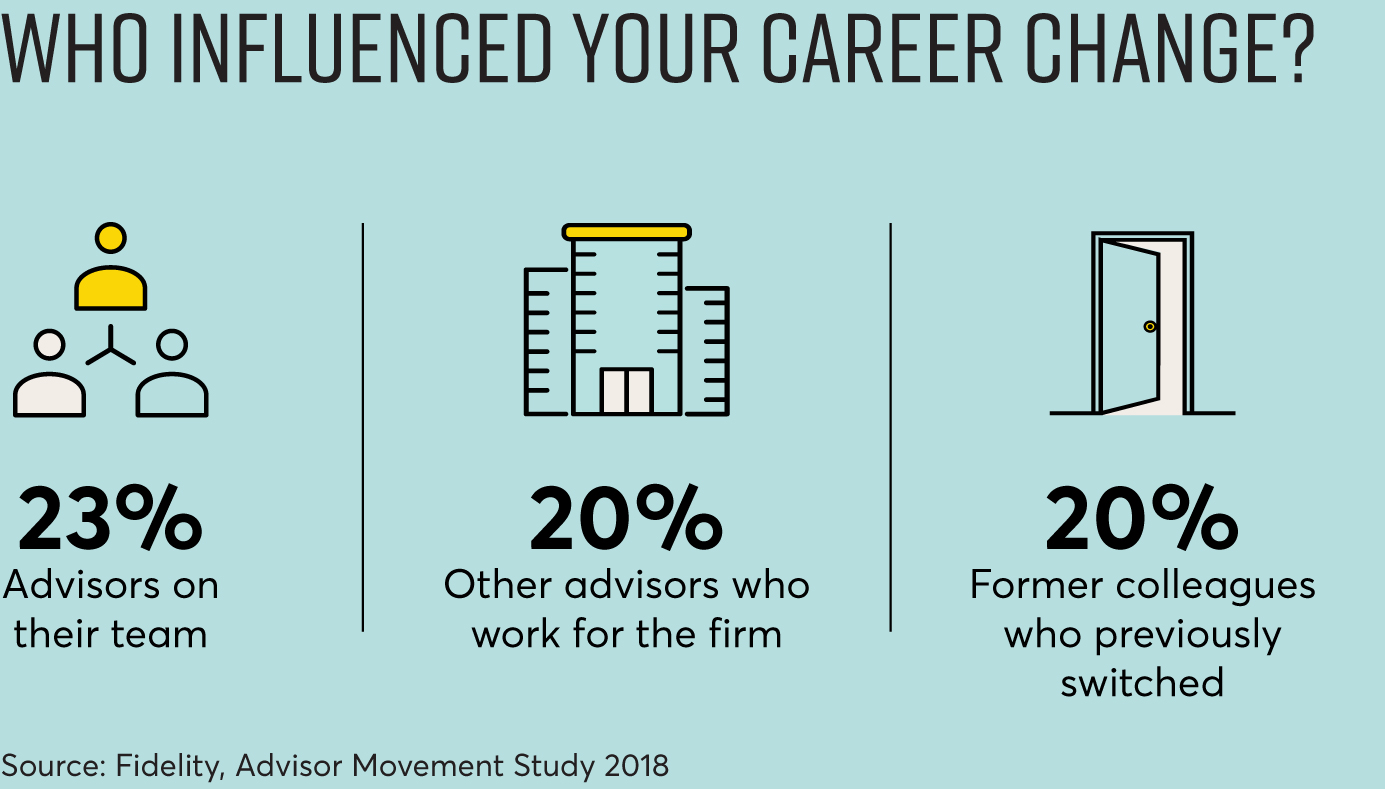

Many more advisors weigh making such moves. More than half of those surveyed by Fidelity said they had considered a career change in the past five years, according to a 2018 survey by the company. At the same time the stakes have gotten higher. The Fidelity survey found that advisors switching firms transferred median assets of $75 million in 2017, up from $37.5 million in 2012.

To better understand the perils and pitfalls of opening one’s own independent shop, Financial Planning reached out to advisors who made that journey in 2018. They shared the ups, downs and unforeseen obstacles they encountered and overcame.

order sushi

Nicole Sennett’s strategy for setting up her independent practice had two unorthodox elements: a chauffeur and sushi.

When the former Merrill Lynch advisor, along with client service associate Cindy Rinehimer, joined the independent side of Raymond James in February 2018, she felt it was important to explain to clients face-to-face why she’d left the wirehouse after 14 years there.

“Our strategy was to have one person in the office at all times, and the other person was out on the road,” explains Sennett, who serves approximately 100 households. “Instead of a phone call, they had me knocking at the door.”

To keep herself free to answer emails and phone calls in between client meetings, Sennett hired a driver who took her from one stop to the next. “It let us cover a lot more ground.”

Sennett also invited clients to a housewarming party at her new office in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania at which she served beverages, cheese platters — and sushi. The party gave her the opportunity to show off her newly independent firm’s goals-planning software on the large flat-screen TV in the firm’s new conference room. The event was a success, she says, as clients who had yet to switch to her new firm agreed to do so on the spot.

Like Sennett, Henley also hit the road while his team members staffed the office and worked the phones.

“The reality is that clients want to see you. Whether they’ve been a client for one year or 20 years, they want to know why you are going independent,” he says.

Plus, Henley landed on the same insight as Sennett did: “I found that clients are so much more willing to sign the paper right then and there in person,” he says.

Of course, if an advisor has clients in many far-flung states, meeting them all in person can be tricky. But deciding which alternate format to use requires thought, says San Diego-based recruiter and consultant Jodie Papike.

“Not everything has to be done in person and in the mail,” she says. “It can be done electronically. But you have to ask yourself, do you have a client base that is comfortable with that? Would they prefer pen and paper?”

Whatever method is used to retain clients, Henley points out that the clock starts as soon as an advisor is out of the wirehouse door, as former colleagues will start calling clients to persuade them to stay.

“While we may have to call 100 families, they may have 10 clients per advisor,” he says.

THE TRUTH ABOUT THE LEARNING CURVE

Asa Graves, whose six-member team left Wells Fargo in August 2018 and previously managed $700 million in client assets, offers a blunt assessment about what it feels like to go independent: “The first two to three months stink.”

“You have the competition of your prior firm trying to keep your clients while you are learning new systems. It’s a heck of a lot to handle all at the same time,” he says.

Advisors often underestimate the amount of paperwork involved, says Papike. “It’s a mighty task. There are services that can help. But it’s still time consuming.”

Factor in, says Graves, that no matter how wonderful new software is and how adept you are at technology, you can’t underestimate the learning curve. He reports that one of the partners instituted a practice each Friday to help keep team members from drowning in the minutiae by asking a simple question: Are things better than last Friday?

“You got to be methodical about it,” Graves says.

“Working at a wirehouse,” he continues, “we didn’t have to be business owners in the sense that, ‘What kind of staffing will I need in a year?’ That’s not the kind of stuff that advisors have to think about, but business owners do.”

By the time the team hit the six-month mark, things smoothed out. The strange and new became familiar and old hat, Graves says, and team members started asking a different question:

“Why didn’t we do this sooner?”

Former Wells Fargo advisor John Agostino experienced a similar trajectory. At his former employer, the work environment was “unhealthy” for advisors, he says. “Even though those [fake accounts] scandals were on the other side of the bank, it still affected us.”

Needing a change, he left Wells Fargo for LPL in November 2018. Still, it was scary, Agostino says. “What if clients don’t follow me?”

But the independent broker-dealer provided him ample support, he says, helping him transition clients and open new accounts. Agostino, who manages $90 million in San Marcos, California, feels rejuvenated. “I have a new spark. I didn’t want to go to work before. It was depressing.”

For advisor Gabriel Gallante, whose $415 million team also moved from Wells Fargo to LPL in April 2018, there’s a fundamental lesson for advisors thinking about going independent: “Don’t doubt yourself.”

“You were able to grow this business for a reason,” the Plainview, New York-based advisor says. “Your clients care about you. They don’t care about a brand. They care about the value and service you deliver and they will stay with you. Be confident in that even though it may be the hardest thing to do.”

CALL AN AUDIBLE

Equally daunting, perhaps, are the numerous software options available to advisors.

“We didn’t want to be vetting 15 CRMs,” says advisor Michael Landsberg, whose $675 million team left Wells Fargo Advisors Financial Network to open its own RIA last August.

Landsberg’s solution to narrowing the field? First, pick your custodian and then use them as a sounding board. “To me, the custodian has to be first. Their ability to interface and integrate is huge,” he says. Ditto other vendors.

“They’ll tell you this works really well with this. Or they say, ‘Oh we’re not familiar with that financial planning software.’ Well that’s a red flag,” he says.

Landsberg also hired a consultant, Fusion Financial, to help them navigate the process. “We’re running a full time business and there are a lot of things we don’t know. In fact, we probably didn’t know what questions to ask.”

Advisors who’ve gone indie also caution that no matter how impressive a demonstration of software tools is, they may operate differently in your practice.

“Prior to launching an RIA, you do an hour demo with these vendors. You might do three or four demos [with each one]. But you can’t really evaluate it until your in the drivers’ seat and actually using it,” Henley says.

The Salesforce-for-Redtail swap wasn’t Henley’s only change-up. His team also stopped using Black Diamond, finding it wasn’t the right fit.

“Our clients are not investment focused, they are planning focused. So we decided to switch to eMoney,” Henley says.

His team also changed the firm’s name two months after launching from Wyeth to Brandywine Oak Private Wealth.

“We actually wanted Brandywine Private Wealth,” Henley says, but it was taken. Later, his trademark attorney suggested adding a word. But the team stressed over the decision; although some clients had made the switch, others had yet to sign the paperwork.

“In our heads, we worried clients would be asking, ‘man what is going on over here?’ The vast majority told us they liked the new name better,” Henley says.

His takeaway? Don’t overthink it.

The point of owning your own firm, independent advisors say, is having the power to make decisions like these. Don’t like your reporting software? Get something that fits better. Don’t like the firm name, or its new name? Change it.

Henley, once a self-described “diehard” Merrill Lynch advisor, says he’s never done something so difficult — and had this much pride in doing it.

“It’s like starting in the business all over again. The same euphoria that I felt when I got into this business, I get it all again. But the difference is that you now own something,” he says.