Over Easter weekend — weeks into the economic turmoil caused by the coronavirus pandemic — Creative Planning founder Peter Mallouk tweeted a vow to his workers:

At Creative Planning, we have taken the forever pledge. No matter how long it takes, we will be here for our team - no workforce cuts and no pay cuts - and our team will be here for our clients. https://t.co/8xl0GAqTOB

— Peter Mallouk (@PeterMallouk) April 11, 2020

“At Creative Planning, we have taken the forever pledge. No matter how long it takes, we will be here for our team — no workforce cuts and no pay cuts — and our team will be here for our clients.”

Why such confidence in the middle of a global health and economic crisis?

It’s as if, DeVoe says, they’d “consulted a crystal ball.”

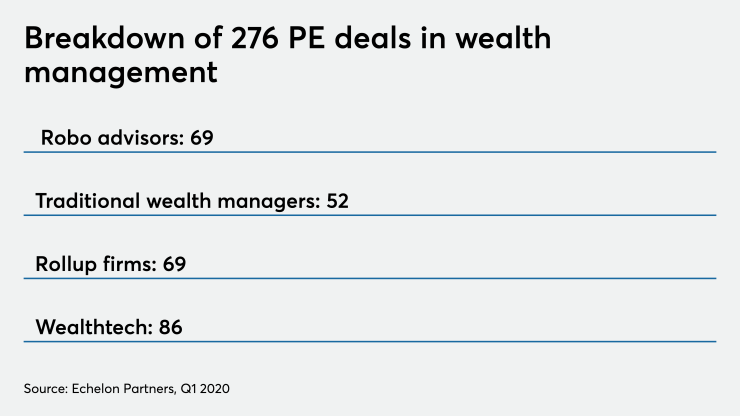

Exquisite timing aside, such deals jibe with a long-building trend. Nearly four times as many private equity investors hold stakes in financial services firms today than they did during the Great Recession in ‘07-’09, according to investment bank and M&A consulting firm Echelon Partners. In all, 276 private equity firms are backing wealth management firms, robos and wealthtechs (fintech firms in the wealth management space, excluding categories such as bank and insurance fintechs), Echelon found. That compares with an estimated 75 firms in 2011.

In the current crisis, PE money, if it proves patient, could provide much-needed ballast for the entire sector.

“They are going to save the industry,” says Echelon founder Dan Seivert, of PE investors who he predicts will continue to inject investment where it’s needed. “They will swoop up any companies that are falling on hard times.”

Conversely, they also could plunge some firms into a danger zone given PE’s reliance on debt to boost returns and growth.

Beacon's President Matt Cooper says some RIAs may have been leveraged five to six times their earnings (calculated before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) before the crisis, an insight echoed by others in the industry who spoke to Financial Planning. As revenue plunged over the past weeks, over-levered firms may be in breach of their debt covenants.

At the same time, PE funds which also have holdings in the harder-hit corners of the economy, such as the restaurant sector, may not have the resources to bolster their financial services holdings. “We are going to find out,” Cooper says.

Despite rampant market volatility, PE investors who focus on the RIA industry said they are confident about its ability to withstand the current market downturn, and point to the move toward advisor independence that followed the last recession.

“The last crisis kicked off this significant wave of independents. You saw the dollar flows and foot traffic of advisors and clients going independent, looking for conflict-free advice,” says Brad Armstrong, a partner with PE firm Lovell Minnick, an investor in independent broker-dealers Lincoln Financial and HD Vest. “It evolved into [investors] discovering this practice had transactable value to them.”

Lovell Minnick bought a piece of multifamily office Pathstone at the end of last year after selling its stake in RIA Mercer Advisors. PE firm

Historically, market depressions have provided opportunities for well-capitalized firms to grow. “When you have scale and you have quality, you can take advantage in downturn,” says Allen Thorpe, a partner at Hellman & Friedman, which owns a majority stake in Edelman Financial Engines, the largest independent RIA in the country with more than $200 billion in client assets. “We’ve seen time and again that these are incredibly high-quality and enduring businesses.”

The financial advice sector is attractive to PE investors thanks to the highly variegated field of entrepreneurs struggling to achieve nationwide reach.

Financial firms look even more attractive now than they did back in 2008-09, says Nick Beim, a partner at venture capital firm Venrock, which was started by the Rockeller family and owns a stake in fintech custodian Altruist.

“The companies that are the leaders in different fintech sectors have very meaningful scale,” Beim says. Partnerships are stronger than they were in the last downturn, he adds, “because these businesses are able to drive a lot of revenue.”

In return for selling off stakes, entrepreneurs running fast-growing RIAs, independent broker-dealers and wealthtechs say they get not only money, but experience navigating companies through downturns — experience that’s coming in handy during the effective nationwide quarantine as PEs sit virtually alongside their C-level executives.

By contrast, public firms’ governance structure is less directly supportive of management, given that there are no stockholders to answer to, says Tony Salewski, managing director at Genstar Capital.

“Our equity sits behind the desk,” says Salewski, whose firm still owns a majority stake in Cetera, one of the country’s largest IBDs. “We are 100% aligned.”

As a rule of thumb, private equity seeks a return on its investment at about the seven-year mark. But not always.

PE firm General Atlantic, a minority owner of Creative Planning, holds investments over five-to 15-year periods, says managing partner Paul Stamas.

“We don’t need to pursue liquidity at any point. We can hold things for quite a long period of time. We are a very, very long-term partner,” Stamas says. Across the sector, PE will offer a “protective” factor for firms, he predicts.

Part of PE firm’s eagerness to invest is predicated upon the premise that most firms will not go under, says Dan Seivert, CEO Echelon Partners.

“In ’08 and ’09, we had probably less than 2% of firms fail,” Seivert says.

‘More in the till’

Should the market continue to deteriorate, PE firms are prepared to make further investments to carry their advisory firms through, Stamas says. “Even for a company we’ve supported for seven years we’ve still got more room in the till,” he says.

Edelman Financial Engines CEO Larry Raffone, who ran one of his company’s predecessor firms, Financial Engines before it merged with Edelman Financial in 2018, says such backing has emboldened him to lean into growth strategies.

“If this [had happened] was when we were public, 18 months ago, our stock would be trading 35% lower,” Raffone said in an interview in early April. “I would be on with callers right now. It would be all crisis control. I’m doing none of that right now. I’m not pulling back on anything.”

Nor does Thorpe want him to, he says. “We don’t care about this month, this week, this quarter,” says Thorpe, whose firm paid $3 billion to take Financial Engines private and complete the merger. “We are not in and out of the stock. We are not thinking about the quarterly earnings. We care about the next five-to-10 years.”

Of historical note, Thorpe points to the fact that his PE firm, Hellman & Friedman, made the first PE investment in LPL in 2005 and held it through LPL’s public offering in 2011. LPL went on to become the largest IBD in the country.

Public problems

PEs and their competitors are tight-lipped about which RIA platforms might face leverage problems, since they could find themselves bidding for or against them in the future. However, one firm whose financials are public, the aggregator Focus Financial, disclosed its net leverage ratio, an expression of debt to earnings, at 4x at the end of last year.

If the downturn is prolonged, Focus could face vulnerabilities, given the way it structures its deals, experts say. “I think Focus Financial has typically been the poster child for, ‘Buy more debt and do more deals,’” Seivert says.

Focus, which went public in July 2018 at $33 a share, saw its stock fall below $14 last month before rebounding back above $20 this week.

John Langston, managing partner of investment banking firm Republic Capital in Houston, which competes with Focus, says the firm is unique in that it takes fixed revenues from each firm it buys.

Focus tells investors, “‘Hey, we’re protected in a downturn,’” Langston says, because it forces its firms to engage in cost cutting. But should the downturn be prolonged, he predicts Focus will come under increasing pressure to bear some of those losses itself.

When contacted for a response to Langston’s comments, a Focus spokeswoman said the company’s public disclosures at the end of 2019 show the aggregator relies on its partner firms to reduce costs in a market swoon. It would also “moderate” its aggressive M&A strategy in such an environment, the disclosures say.

Matt Sonnen, an industry consultant who used to work at Focus, thinks nobody should bet against Focus or its CEO Rudy Adolf.

“I’m not personally worried about them,” Sonnen says. “I think Rudy is pretty darn smart. I know there’s been a lot of speculation about their debt levels and everything, but I don’t think they’ve leveraged that thing to the hilt.”

Hot cup of Joe

PE could be a lifeboat for smaller companies given the age of many advisors, says DeVoe, who predicts there just won’t be enough buyers to handle overwhelming demand from smaller firms for shelter.

Given an average age among RIA owners — 55, according to J.D. Power, fully 70% of firms have no succession plan in place, according to DeVoe, who calls the global downturn a “hot cup of coffee” for advisors who’ve been procrastinating on selling.

“We are going to need more acquirers,” says DeVoe, who is now hiring at his own firm to handle the increased workload. “We need more buyers to absorb all the firms that will need to be acquired.”

Lovell Minnick was ready to deploy “emergency capital” to help firms through the last downturn and is poised to do so again, should it be needed, Armstrong says. But this time around he expects to make more strategic acquisitions and hires, as opposed to conducting rescue operations.

If Creative Planning is a bellwether, he may have numerous options to consider. Last month the firm posted one of the highest influxes of new clients ever, Mallouk claims, even after the economy ground to a near halt. His goal is to keep enough advisors employed to serve them.

After his weekend tweet, Mallouk, in an interview with Financial Planning, challenged other RIAs to publicly follow his lead and commit to no payoffs or pay cuts for six months.

“I would like to leave the industry having never let go of anybody ever because of market conditions,” Mallouk says.

Of 10 firms contacted, none took up the call.