The

However, baked into the law was one provision that amounted to a significant tax increase for a certain subset of taxpayers: State and Local Taxes (SALT), which, prior to TCJA, individual taxpayers were able to take as itemized deductions up to the full amount of any income, property and/or sales taxes paid to any state or municipal government. After the passage of TCJA, though, these taxes were deductible by individual taxpayers only up to a maximum of $10,000. That $10,000 cap on the SALT deduction is the same for both single and married filing jointly taxpayers, and isn't indexed to inflation –— meaning that no matter how much a taxpayer pays in state and local taxes (and no matter whether those taxes are paid by a single filer or both spouses on a joint return), the $10,000 cap remains the same up through the (currently scheduled) expiration of the law in 2025.

The effects of the SALT deduction cap hit heaviest on high-income taxpayers in high-tax states like New York and California. For example, a couple in California with $400,000 in taxable income in 2022 and in the 9.3% tax bracket would have owed $30,707 in state income taxes. While those taxes would have been fully deductible pre-TCJA, the law caps this amount at $10,000, amounting to an increase in taxable income of $30,707 – $10,000 = $20,707.

Furthermore, the cap applies to taxpayers' combined income and property taxes, meaning that if those taxpayers owned a home as well, none of their property taxes would be deductible since their income taxes already put them over the limit.

Legislators in the U.S. House and Senate representing constituents in higher-tax states have pushed for a repeal of the SALT cap provision in the years since TCJA, but so far without success. With Republican lawmakers preferring to raise taxes on residents of majority-Democrat states to avoid doing so on their own constituents, and more progressive politicians being loath to approve a tax cut that would primarily benefit high-income taxpayers, the SALT cap appears to have at least enough of a coalition to last until it's scheduled to sunset after 2025.

With no changes to the SALT cap on the horizon from the federal side, state and local governments began to devise ways to allow their residents to preserve the deductibility of their state and local taxes shortly after the SALT cap took effect during the 2018 tax year.

Some states tried to take advantage of the deductibility of qualified charitable contributions as a federal itemized deduction (which, while subject to income-based limits, are not limited to $10,000 like the SALT deduction) to work around the SALT deduction limit, with states and municipalities setting up local charitable funds (or specifying existing charities) that taxpayers could contribute to in exchange for a credit against their state taxes, effectively structuring the state tax payments as charitable contributions that would be allowable as federal itemized deductions without the $10,000 limit. However, the IRS 2019

However, a different type of state tax workaround took advantage of the fact that, unlike individual taxpayers, businesses are allowed to deduct state and local tax payments against their income with no limitation — meaning that if taxpayers with business income were able to recharacterize their state tax payments from a personal to a business expense, they would effectively avoid the $10,000 SALT deduction limit.

In 2018, Connecticut became the first state to enact a Pass-Through Entity Tax (PTET), which, in a nutshell, turns state tax payments for certain business owners into deductible business expenses — and unlike the charitable contribution scheme, this strategy was given the IRS's blessing in

But while PTETs are a functional workaround to the federal SALT deduction limit, they aren't necessarily a simple one. With 33 different sets of state laws governing PTETs — each with their own rules dealing with tax rates, credits, electing and filing requirements, procedures for residents versus nonresidents and so forth — the value of electing a PTET can vary widely depending on the state(s) where the business and its owners are located, and the individual circumstances of each.

Electing a PTET isn't always a slam dunk, and while the full analysis is best left to a tax professional, a deeper understanding of the mechanics of PTETs, major considerations in deciding whether or not to elect, and some of the tax planning opportunities associated with PTETs can help advisors get a handle on this complex but potentially valuable planning tool.

How PTETs work

Normally, "pass-through" business entities like partnerships and S corporations don't pay income taxes themselves. Rather, business income and expenses are usually calculated on the business's own tax returns (

Example 1: Tom and Ray are equal 50% partners of Tappet Brothers Auto Repair in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In 2022, the business had $1 million in net income. Normally, Tom and Ray would each include their share of the business's net income (50% x $1M = $500K) on their personal tax returns. Massachusetts has a flat tax rate of 5%, so (assuming no other deductions or credits that might apply) each brother would owe 5% × $500K = $25K in Massachusetts state tax on their business income for 2022.

However, because their state tax was assessed and paid on their personal Massachusetts state tax returns, the deductibility of their state tax payments for federal tax purposes is limited by the $10,000 SALT deduction cap — meaning that $25,000 − $10,000 = $15,000 of each brother's state tax payments cannot be deducted (and potentially more if they had paid other types of state or local taxes, like real estate property taxes, that are subject to the same SALT deduction cap).

With PTETs, states allow owners of pass-through businesses to choose a different method of taxing their business income by taxing the business entity itself, rather than the individual owners. The details vary by state, but in general the mechanics of PTETs can be best understood as a three-step process.

- The business owner(s) must make an election for the PTET, subjecting the business to the state tax based on its income for the year which is then paid at the entity level.

- The business owners receive a tax credit on their personal state tax returns for most or all of their proportional share of the PTET paid by the business, reducing their individual state taxes to offset the taxes paid at the entity level. In some states the credit equals 100% of the PTET paid, fully offsetting the tax paid by the business, while in other states the proportion is less than 100%, meaning that some amount of business income is effectively double-taxed by the state, both at the entity and the personal level.

- The state tax payment paid by the entity is included as a deductible business expense on the business's Federal tax return, lowering its net income (and therefore also lowering the net income that is divided among each of its owners and passed through to their federal tax returns).

Example 2: As Example 1 above described, without electing the PTET, Tom and Ray would be impacted by the Federal SALT deduction cap, limiting their deduction to $10,000 each despite each paying $25,000 in state income tax on their business income.

If Tom and Ray elected into Massachusetts' PTET, however, the business would pay the state tax at the entity level instead of on the brothers' personal returns, making it fully deductible as a business expense.

To elect into the state PTET, Tom and Ray take the following steps:

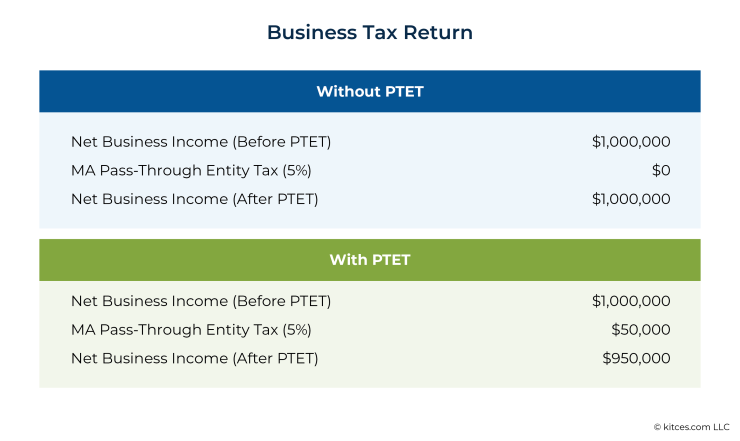

First, the business elects into Massachusetts's PTET and pays the state's statutory PTET rate — which is 5%, the same as the personal tax rate — on its $1 million of net income, resulting in a total state tax of 5% × $1M = $50K.

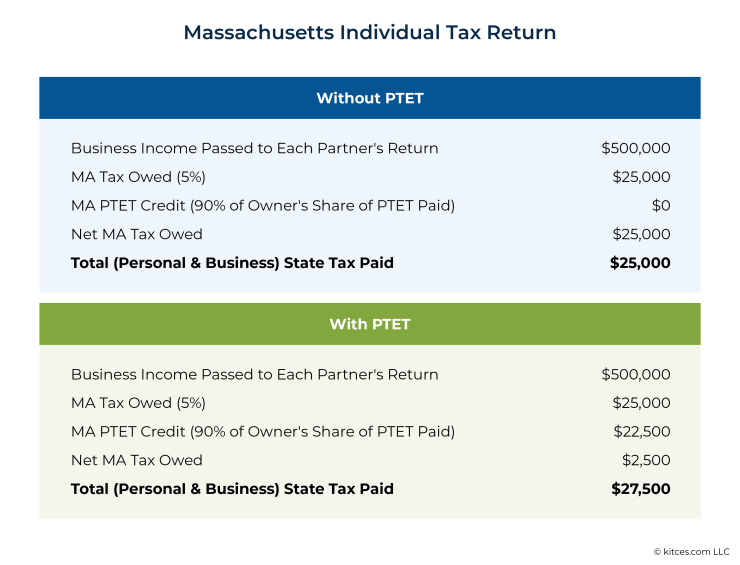

Next, after the business elects and pays the PTET, Tom and Ray are entitled to a state tax credit against their personal state taxes. In Massachusetts, this amounts to 90% of each owner's share of the PTET paid. Each brother's share of the PTET is 50% x $50,000 = $25,000, so their state PTET tax credits equal 90% x $25,000 = $22,500. Each brother's personal state income tax is reduced from $25,000 to $25,000 − $22,500 = $2,500.

Finally, the $50,000 PTET paid by the business is deducted on the firm's Federal business tax return, reducing its net income to $1,000,000 – $50,000 = $950,000 before being passed through to the owners.

Notably, the brothers pay slightly more in total state income tax with the PTET than without it since Massachusetts only allows a credit of 90% of the PTET paid. Without the PTET, they would each pay $25,000 in individual state income tax, while with the PTET they would each pay $25,000 (each brother's share of the PTET) plus $2,500 in individual state income tax left over after the PTET credit, totaling $25,000 + $2,500 = $27,500.

However, the reduction in Federal income tax from electing the PTET can more than make up for the higher state income tax. Assuming Tom and Ray are in the 32% Federal tax bracket, the SALT deduction without the PTET is only 'worth' 32% x $10,000 = $3,200.

With the PTET, however, they are each able to deduct the full $25,000 in taxes paid by the business, plus the $2,500 in individual income tax as an itemized deduction, for a total of $25,000 + $22,500 = $27,500.

In the 32% tax bracket, that amounts to a 32% x $27,500 = $8,800 reduction in federal tax — $5,600 more than without the PTET.

In other words, electing the PTET raised Tom and Ray's Massachusetts state taxes by $2,500 each, while lowering their Federal taxes by $5,600 each, for a net tax savings of $3,100 per brother.

In effect, then, the mechanics of PTETs are much more complicated than simply shifting state tax payments from being a personal expense (deductible only up to the $10,000 SALT deduction limit) to a (fully-deductible) business expense for federal tax purposes. Different states have different nuances (such as Massachusetts' allowing a credit for only up to 90% of the PTET paid) that affect the value of electing any given state's PTET.

In reality, there is a wide swath of factors that business owners need to consider when deciding whether or not to elect a PTET, since in some cases electing a PTET could result in paying more taxes overall — or the savings could be small enough that they aren't worth the extra effort of electing the PTET and correctly following all of the subsequent steps.

Considerations for PTETs

In an ideal world, electing a PTET would be a simple matter paying the exact same amount of state income tax, only shifting the state tax payment from a (deductible only up to the $10,000 SALT cap) personal expense to a (fully-deductible) business expense — in that world, it would almost always make sense to recommend owners of pass-through businesses to make the election for a PTET. In practice, however, the differences between how different states treat the nuances of PTETs in their tax codes means that electing a PTET isn't always the best move.

PTETS can result in higher state taxes

The first high-level consideration in deciding whether it's worth it to elect a PTET is how the state's tax rate for pass-through entities compares to the tax rate that the taxpayer would pay without the PTET. In many states, electing a PTET will result in paying a higher amount of state tax than without the PTET because most states tax pass-through entities at a flat rate, whereas personal income is usually taxed progressively. In other words, with a PTET, all of each partner or owner's share of business income is taxed at a single rate, whereas if that income passed through to their personal tax return it would usually be taxed at a mix of lower and higher rates.

Example 4: Hugh, Louis, and Stuart are equal 33.3% owners of the law firm Dewey, Cheetham, and Howe, based in California. In 2022, their firm had $1,000,000 of net income.

Pass-through entities that elect California's PTET pay a flat rate of 9.3% on their net income. If the firm elected the PTET, then, it would pay $1,000,000 x 9.3% = $93,000, or $93,000 ÷ 3 = $31,000 per partner.

If the law firm partners don't elect the PTET, then each of their share of the partnership's net income ($1,000,000 ÷ 3 = $333,333) would pass to their individual tax returns and be taxed at California's personal tax rates, which

Electing the PTET, then, would result in each partner paying $31,000 − $27,270 = $3,730 in additional state tax.

However, because they would be able to deduct the full $31,000 PTET as a federal business deduction rather than being limited to a $10,000 SALT deduction on Schedule A, electing the PTET results in a $31,000 − $10,000 = $21,000 reduction in federal income.

In the 32% tax bracket, that amounts to $6,720 in federal income tax savings, meaning that overall election of the PTET saves $6,720 − $3,730 = $2,990 in total taxes for each partner.

In states where electing the PTET does result in paying more state taxes, such as in Example 4, above, it can still be worth doing so if the business owners can reduce their federal taxes enough by being able to fully deduct the state PTET as a business expense to make up for the higher state tax. The interplay between state and federal taxes means it's necessary to take a holistic view of a client's tax situation and determine if their combined (state and federal) tax bill will be higher or lower by electing a PTET.

In most states, the PTET is set to a rate equal to the state's top individual income tax rate — meaning that if the business owner isn't actually in the highest tax bracket, they'll pay a higher state tax rate on all of the business's income with the PTET than they would on any of their income at the individual state tax rates. Likewise, two states — New Jersey and Wisconsin — have a PTET rate that is higher than any of their individual tax brackets, meaning that taxpayers in those states will almost always pay higher state taxes with the PTET than without.

A number of states that impose flat individual income tax rates set their PTET rate to an equal amount, meaning that business owners' income in those states would theoretically be taxed at the same rate whether or not they elected the PTET. However, other factors can affect the actual amount of state tax paid; for instance, as shown in the examples in the previous section, Massachusetts only allows a credit for 90% of each owner's share of PTET paid, meaning that pass-through business owners there may effectively pay tax both at the entity level and the individual level on a small portion of their income.

It's also worth noting that in a handful of states, the PTET rate is actually lower than the highest state income tax rate, meaning that electing the PTET would likely reduce the amount of taxes paid. As of May 2023, only California, Louisiana, Maryland, Ohio, and South Carolina have PTET rates that are lower than their top tax bracket.

Effects of PTETs on federal taxes

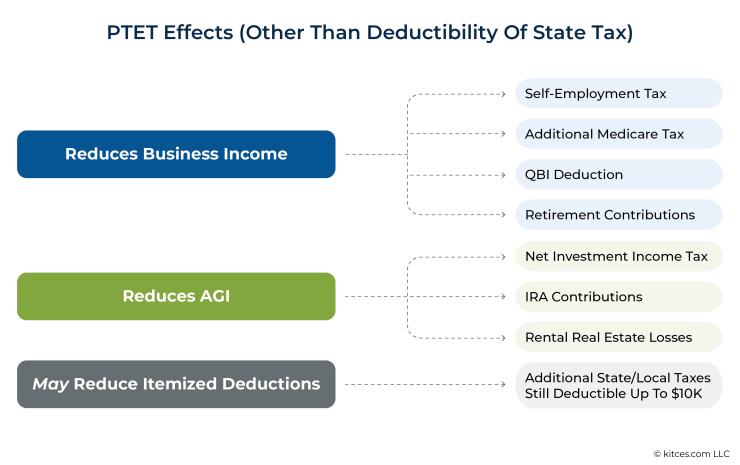

Although PTETs are enacted and implemented at the state tax level, the primary (and best-known) effect of PTETs is to reduce federal taxes by circumventing the SALT deduction cap making state tax payments deductible as a business expense for owners of pass-through entities. However, there are other less-well-known effects of PTETs on Federal taxes that are worth considering for planning purposes.

The first and most notable is that, whereas the traditional SALT deduction is an itemized deduction on Schedule A and therefore comes after calculating the taxpayer's Adjusted Gross Income (i.e., is a "below-the-line" deduction), a PTET, as a deductible business expense, is an above-the-line deduction that can actually serve to lower the taxpayer's AGI. And because many other deductions, credits and other tax thresholds are tied to a taxpayer's AGI (e.g., the

Additionally, as a deductible business expense, a PTET serves to reduce a taxpayer's business income, which can have further downstream effects. For example, if the business income is taxed as self-employment income, the PTET can reduce the amount of income that is subject to self-employment tax (and to

Finally, it's worth reflecting on the fact that, because the PTET effectively shifts state and local tax payments from being an itemized deduction on Schedule A to being a deductible business expense, a PTET election can also affect the taxpayer's other itemized deductions (and whether they even continue to itemize or instead take the standard deduction).

If the taxpayer has other state and local tax payments (e.g., property taxes and state income taxes on nonbusiness income) such that their total SALT deduction would have been at or near the $10,000 limit even without paying state tax on their pass-through entity income, then electing the PTET will have minimal effect on the amount of their itemized deductions. In some limited cases, however, moving the state tax payments on pass-through entity income off of Schedule A will drop the total itemized deductions below the amount of the standard deduction, and it might be beneficial to start using

Even though the full deductibility of state and local taxes is often the primary motivation for electing a PTET, the additional downstream effects — both positive and negative — can also have a significant impact on a pass-through entity owner's tax situation.

Multi-state partnerships (and partners in multiple states)

Many professional service businesses like law, accounting and financial advisory firms do business in multiple states, and in an era of virtual work having different partners located around the country has become increasingly common, meaning that many partnerships may have the option to elect PTETs in multiple states. However, the complexity of electing and managing PTETs greatly increases when a pass-through entity does business in (and/or has owners located in) multiple states: the tax rates, credit allowances, and eligibility rules for PTETs vary from state to state, meaning that the analysis of whether or not to elect a PTET might be slightly different in each state where the entity does business.

The biggest single concern for owners of pass-through entities filing in multiple states might be whether their home state will allow a credit for tax paid to other states when that tax is paid as a PTET at the entity level. Typically, when a taxpayer lives in one state but earns income in another, the tax on that income is calculated and assessed by both states — but in most cases the "home'" state allows a credit for the tax that the taxpayer paid to the state where the income was earned, so the individual only needs to pay tax once on the income.

However, that's usually only the case when the individual pays the tax to the other state, which means that when the entity, rather than the individual, pays the tax — as is the case with a PTET — the usual credit for tax paid doesn't necessarily apply. Meaning that a taxpayer who lives in one state and earns income from a pass-through entity in another (such as when the entity does business in multiple states), and who elects the PTET in the state where the income is earned, may end up paying two sets of state taxes on the same income: one at the entity level in the state where the income is earned, and one at the individual level in the taxpayer's home state, unless the home state has otherwise provided that they allow a credit for a pass-through entity owner's share of PTET paid to another state.

Unfortunately, not every state has provided guidance about their treatment of PTETs paid to other states as it relates to credits for tax paid, but most of the ones that have do allow tax credits to residents for PTETs paid to other states. Two notable exceptions are Pennsylvania,

Example 5: Picov Andropov is a chauffeur who lives in Gary, Indiana and commutes to Chicago for work. He earns $100,000 in wages, which are taxed both by Illinois (the state where the income was earned) and Indiana (the state where he lives).

Illinois has a flat income tax rate of 4.95% and Indiana has a flat rate of 3.23%, meaning that Picov's calculated state taxes would be 4.95% x $100,000 = $4,950 to Illinois and 3.23% × $100,000 = $3,230 to Indiana. However, Indiana allows a nonrefundable credit for taxes paid by residents to another state, reducing Picov's Indiana state tax to $0.

Picov is also a partner in a car-ferrying business based in Chicago. His share of profits from that business was $100,000, and the business has elected into Illinois' PTET. Like his wage income, his partnership income is taxed both by Illinois and Indiana, with Illinois assessing its PTET rate of 4.95% on the business directly and Indiana assessing its 3.23% rate on Picov's share of the partnership income.

However, Indiana does not recognize the PTET for the purposes of calculating its credit for tax paid to other states, meaning that Picov would pay tax twice on his share of the partnership income: $4,950 (his share of the Illinois PTET) plus $3,230 (the Indiana tax on his share of business income).

Another concern for owners of pass-through entities in multiple states can be the requirements for filing individual tax returns in any state where the business elects a PTET. In many states, pass-through entities are allowed to file a single consolidated tax return on behalf of all of their nonresident owners in lieu of each out-of-state owner needing to file a separate individual tax return in that state.

But when a pass-through entity elects a PTET, many states require all of the entity's owners — both in- and out-of-state — to file individual tax returns in order to claim the state tax credit against their share of the PTET. Which means that partners of firms that do business in many states may need to file individual tax returns in all of those states if the business elects a PTET, and the additional cost and complexity of filing separate tax returns for each state where a PTET is elected could ultimately negate any tax savings that would have been created by electing the PTET to begin with.

Finally, it's worth noting that, depending on the ownership structure of the business, any individual owner or partner in a pass-through business might not have much control over whether the business elects a PTET in any given state. A few states require 100% of a electing firm's ownership to agree to the election, and others may allow some of the business' individual owners to opt out of paying the PTET on their share of income — but most states don't have such stipulations, meaning that the decision is ultimately up to how the business's governing documents provide for making business decisions, e.g., by a majority vote of S corporation shareholders or partnership interests. So in some cases, the questions for an individual pass-through entity owner may not focus so much on deciding whether to elect the PTET, but instead on what to do — e.g., choosing what forms to file and what planning decisions will make the best use of the entity-level tax — when the partnership elects into the PTET.

Planning opportunities for PTETs

As seen so far, there are myriad considerations that go into deciding whether or not to make a PTET election. The calculus can change depending on the income or nature of the business itself, the individual tax situations of the entity's owners, the state(s) where the owners are located and do business, and the interplay between state and federal tax when it comes to PTETs mean that running the numbers on the taxpayer's entire tax situation is the best (and often the only) way to decide whether it makes sense to elect paying taxes at the entity level.

But it isn't always feasible to run a full analysis for every pass-through business owner. Instead, it can be helpful to look at a progression of criteria — starting with broad and easy-to-find characteristics and narrowing into more specific detail — that can help with determining whether a PTET election is even worth considering before wading further into a fuller analysis.

The highest level of criteria for when electing a PTET might make sense can include when:

- The taxpayer is the owner of a pass-through entity;

- The taxpayer lives in a high-income-tax state; or

- The taxpayer is in a high Federal income-tax bracket.

Going further, the following criteria can help narrow down the decision for an individual who meets the above characteristics as to whether it still makes sense to elect a PTET:

- The state's PTET rate is equal to, or less than, the owner's individual state income tax rate (or is close enough to be offset by the federal tax savings;

- The taxpayer earns self-employment income from the pass-through entity, and/or is subject to the Net Investment Income Tax or Additional Medicare Tax that would be reduced by deducting state taxes from net business income;

- The state allows a refundable credit to offset all of each owner's share of the PTET paid; or

- The taxpayer's resident state allows a credit for taxes paid to another state that applies to the taxpayer's share of a PTET.

Finally, this last set of criteria can help determine whether, from a practical standpoint, electing a PTET (and meeting the filing and payment requirements) will be feasible for the business entity and/or the taxpayer:

- The pass-through entity's income is mostly sourced from the state where the taxpayer lives, and most of the entity's owners live in the same state;

- The other owners of the entity are on board with making the election, and will receive a similar benefit from making the PTET election; or

- The business entity has the cash flow needed to make any necessary estimated payments required to elect and/or pay the PTET.

Business structure changes to qualify for PTET

Most states only allow certain types of business entities to elect their PTET. Partnerships and S corporations are generally fair game, but C corporations (which usually already pay an entity-level tax, negating the need for a separate pass-through entity tax) and "disregarded entities", i.e., sole proprietorships and single-member LLCs (which have a single owner who files a Schedule C on their individual tax return rather than a separate business return), are usually excluded from PTET eligibility.

Disregarded entity owners who want to take advantage of a PTET — but are precluded from doing so by their state's PTET rules — could consider a change in business structure that allows them to be eligible for the PTET. In general, they could do this in one of two ways: 1) make an election to be taxed as an S corporation, or 2) add a business owner to become a partnership.

By filing

Making an S corporation election is

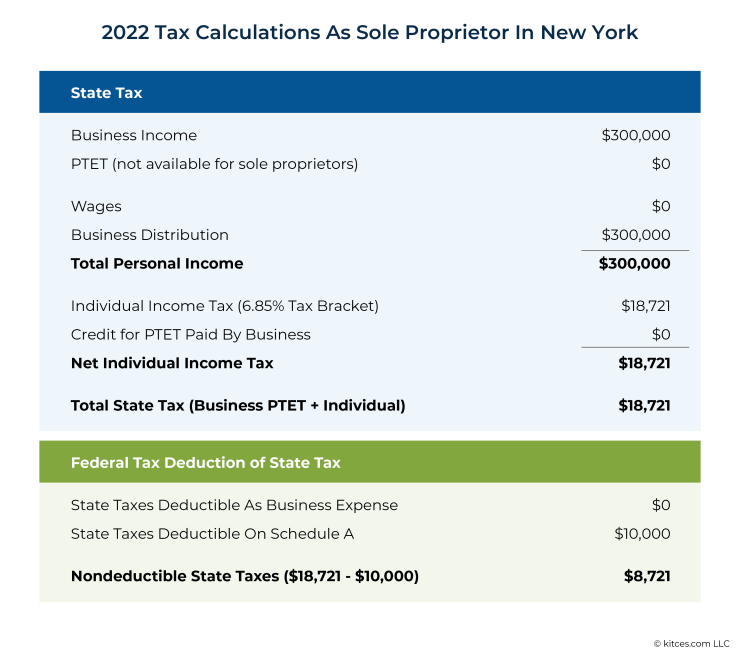

Example 6: Marge Innovera is a freelance statistician based in upstate New York. She operates as a sole proprietor and earns $300,000 per year in New York taxable income. She files as a single taxpayer and is in the 6.85% state income tax bracket for 2022.

As a sole proprietor, Marge is ineligible to elect into New York's PTET. Based on her income, as shown below, she would pay $18,721 in New York individual income tax, of which only $10,000 would be deductible as an itemized deduction on Schedule A for Federal tax purposes (because of the SALT deduction cap, assuming there are no other state or local tax payments that would reduce that amount further). This would leave Marge with $8,721 in nondeductible state taxes.

So Marge decides to turn her business into an S corporation, paying herself a wage of $100,000 and treating the remaining $200,000 as a distribution of business income. As shown below, if she elects New York State's PTET (which

She can take that same amount as a credit against her individual state income tax, meaning that of her $18,721 total state tax bill, $13,700 is paid at the entity level from her S corporation, and $18,721 − $13,700 = $5,021 is paid at the individual level.

What this means for Marge's federal income taxes is that the $13,700 of tax paid by the S corporation is fully deductible as a business expense from her net business income, while the remaining $5,021 paid on her individual state tax return is deductible as an itemized deduction on her Schedule A.

And because the $5,021 of state tax that was paid at the individual level is less than the $10,000 SALT deduction cap, the whole amount is now includable as an itemized deduction on Schedule A (assuming she has other deductions, like mortgage interest or charitable contributions, that would allow her to itemize).

In other words, by turning her business into an S corporation and electing the New York state PTET, Marge is able to deduct her entire $18,721 in state tax payments, versus the $10,000 that she would have been limited to as a sole proprietor.

Assuming she's in the 35% federal tax bracket, that's 35% x $8,721 = $3,052 in federal tax savings — and that's before considering the savings in self-employment tax or any of the downstream effects on federal tax described above!

The other potential option for a sole proprietor to become eligible for a PTET would be to add a business owner to become a partnership, which is generally an eligible type of entity for a PTET. Even though forming a partnership involves fewer administrative requirements than forming an S Corporation, doing so is still obviously not a decision to take lightly, since adding owners means splitting profits as well as responsibilities in running the business. But if a sole proprietor was already considering adding an owner — e.g., by making a current employee into a partner in the business, or by merging with a different sole proprietor — the PTET ramifications might make a partnership worth considering a little earlier than the owner would have otherwise.

Fully conveying the state-by-state intricacies of PTETs could take up the space of many articles, and what's above has really only scratched the surface of the topic. However, understanding the general mechanics of PTETs, some of the major considerations of whether or not to elect them, and the types of client profiles that could potentially benefit most, can go a long way towards helping advisors make headway in advising their clients on when and how to use PTETs. Ideally working with a tax practitioner who can run the numbers between different scenarios (and different states if need be), advisors can provide great value by helping clients understand when they should elect into a state's PTET, and what steps they need to take to do so.

And with three tax years remaining — including 2023, 2024, and 2025 — during which the current SALT deduction cap will be in effect (and numerous states offering the potential for retroactive elections from 2022 and earlier), now is a great time to start providing that value!