Borrowing money has a cost. The whole point of saving and investing is to avoid borrowing and instead have the money on hand to fund future goals.

A 401(k) loan, however, presents a thorny case. The employee literally borrows their own money out of their own account, such that the borrower’s 401(k) loan repayments of principal and interest get paid right back to themselves. Consequently, even though the stated 401(k) loan interest rate might be 5%, the borrower pays the 5% to themselves, for a net cost of zero.

That doesn’t mean a 401(k) loan should be considered part of an investment strategy. Indeed, the opportunity cost of not investing the money that would otherwise go into the 401(k), combined with sacrificed tax-deductibility and employer matching, makes it an exceptionally poor investment vehicle.

So why do people borrow against their 401(k) plans in the first place? Good question.

401(k) LOAN RULES

Contributions to 401(k) and other employer retirement plans often have restrictions against withdrawals until an employee retires, or at least separates from service. As a result, any withdrawals are taxable and potentially subject to early withdrawal penalties, and even just taking a loan against a retirement account is similarly treated as a taxable event under

Yet from time to time, employees may need to access the funds in their 401(k) plan before retirement, at least temporarily.

To help address the need, Congress created

The first restriction on a 401(k) loan is that the total outstanding loan balance cannot be greater than 50% of the vested account balance, up to a maximum cap on the balance of $50,000 for accounts with a value greater than $100,000. Notably, under IRC Section 72(p)(2)(ii)(II), smaller 401(k) or other qualified plans with an account balance lower than $20,000 can borrow up to $10,000, even if it exceeds the 50% limit, although

IN PRACTICE

In practice, this means plan participants will still be limited to borrowing no more than 50% of the account balance, unless the plan has other options to provide security collateral for the loan. If the plan allows it, the employee can take multiple 401(k) loans, though the above limits still apply to the total loan balance — i.e., the lesser-of-$50,000-or-50% cap applies to all loans from that 401(k) plan in the aggregate.

Second, the loan must be repaid in a timely manner, which under

If the loan is used to purchase a primary residence, the repayment period may be extended beyond five years at the discretion of the 401(k) plan, and is available as long as the 401(k) loan for down payment is used to acquire a primary residence — regardless of whether it is a first-time homebuyer loan or not. On the other hand, there is no limit or penalty against prepaying a 401(k) loan sooner.

Notably, a 401(k) plan may require that any loan be repaid immediately.

if the employee is terminated or otherwise separates from service — where “immediately” is interpreted by most 401(k) plans to mean the loan must be repaid within 60 days of termination.

On the other hand, 401(k) plans do have the option to allow the loan to remain outstanding, and simply allow the participant to continue the original payment plan. However, the plan participant is bound to the terms of the plan, which means if the plan document specifies that the loan must be repaid at termination, then the five-year repayment period for a 401(k) loan — or longer repayment period for a 401(k) loan for home purchase — only applies as long as the employee continues to work for the employer and remains a participant in the employer retirement plan.

To the extent a 401(k) loan is not repaid in a timely manner — either by failing to make ongoing principal and interest payments, not completing repayment within five years, or not repaying the loan after voluntary or involuntary separation from service — a 401(k) loan default is treated as a taxable distribution, for which the 401(k) plan administrator will issue a

Ultimately then, there is no lender at risk, as the employee is simply borrowing his/her own money, and with a maximum loan-to-value ratio of no more than 50% in most cases, given the 401(k) loan borrowing limits.

In fact, a 401(k) loan is technically more akin to the employee receiving a non-taxable advance on their 401(k) account balance, as ultimately the plan administrator simply liquidates and distributes the employee’s own money to them, and the subsequent repayment of principal and interest simply goes back to the employee’s account. In other words, the employee’s 401(k) loan repayments are really just making principal and interest payments to themselves — or rather, to their existing 401(k) account — not to a lender, as would be the case with a traditional loan or a

Any portion of a 401(k) plan that has been loaned out will not be invested and thus will not generate any return.

On the other hand, since a 401(k) loan is really nothing more than the plan administrator liquidating a portion of the account and sending it to the employee, any portion of a 401(k) plan that has been loaned out will not be invested and thus will not generate any return. In addition, to ensure that employees repay their 401(k) loans in a timely manner, some 401(k) plans do not permit any additional contributions to the 401(k) plan until the loan is repaid — i.e., any available new dollars that are contributed are characterized as loan repayments instead.This means that they would not be eligible for any employer matching contributions. Other plans do allow contributions eligible for matching, on top of loan repayments, as long as the plan participant contributes enough dollars to cover both.

It’s also notable that because there is no lender profiting from the loan many 401(k) plan administrators charge some processing fees to handle 401(k) loans, which may include an upfront $50-$100 fee and/or an ongoing annual service fee, typically $25-$50/year, if assessed.

Nonetheless, the appeal of the 401(k) loan is that as long as the balance is repaid in a timely manner, it provides a means for the employee to access at least a portion of the retirement account for a period of time, without having a taxable event — as would occur in the case of a

THE 401(k) FALLACY

Beyond the appeal of the relative ease of getting a 401(k) loan — given the absence of loan underwriting or credit score requirements — and what is typically a modest 401(k) loan interest rate of about 5% to 6% in today’s low-yield environment, some conservative investors also periodically raise the question of whether it would be a good idea to take a 401(k) loan just to increase the rate of return in the 401(k) account. In other words, is it more appealing to earn a 5% yield by paying yourself 401(k) loan interest, than it is to leave it invested in a bond fund in the 401(k) plan that might only be yielding 2% or 3%?

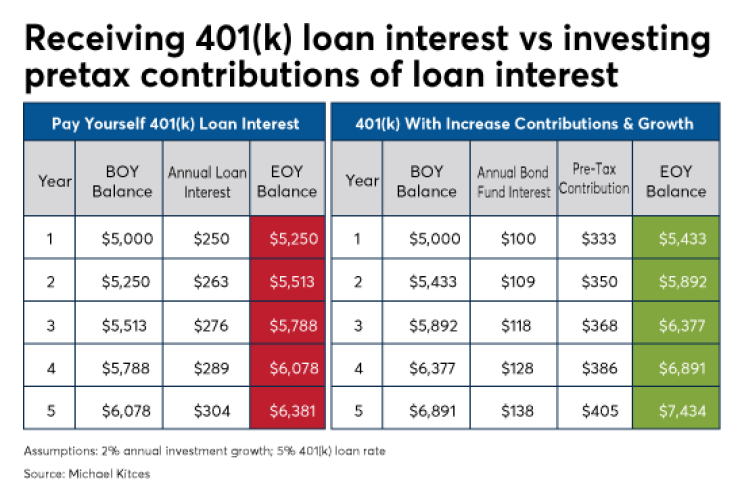

Example 1. John has $5,000 of his 401(k) plan invested into a bond fund that is generating a net-of-expenses return of only about 2% annually. As a result, he decides to take out a 401(k) loan for $5,000, so that he can “pay himself back” at a 5% interest rate, which over five years could grow his account to $6,381 — far better than the $5,520 he’s on track to have in five years when earning just 2% from his bond fund.

Yet while it is true that borrowing from the 401(k) plan and paying yourself back with 5% interest will end out growing the value of the 401(k) account by 5% per year, there is a significant caveat: It still costs you the 5% interest you’re paying, since paying yourself back for a 401(k) loan means you’re not only receiving the loan interest into the 401(k) account from yourself, but also paying the cost of interest too.

After all, in the earlier example, at a 2% yield John’s account would have grown by only $412 in five years, while at a 5% return it grows by $1,381. However, earning 2% annually in the bond fund costs John nothing, while earning $1,381 with the 401(k) loan costs John $1,381, i.e., the same amount of interest he has to pay into the account, from his own pocket, to generate that interest.

Yet if John had $1,381 available to pay into the 401(k) account as loan interest, he also could have simply saved and invested that money for himself. In other words, John already has the $1,381 — inside of his 401(k) account as loan interest, or outside the account ready and waiting to pay. Except if he didn’t use it for loan interest to himself, he could have invested it for a return too.

Example 2. Continuing the prior example, John decides that instead of taking out the 401(k) loan to pay himself 5% interest, he keeps the $5,000 invested in the bond fund yielding 2%, and simply takes the $1,381 of interest payments he would have made and invests them into a similar fund also yielding 2%. After five years of compounding returns, he would finish with $5,520 in the 401(k) plan and another $1,435 in additional savings — i.e., the $1,381 of interest payments, grown at 2%/year over time — for a total of $6,955.

Notably, just investing the money that would have been paid in loan interest, rather than actually paying it into a 401(k) account as loan interest, results in total account balances that are $574 higher. This is exactly the amount of additional growth at 2% peryear that was being earned on the 401(k) account balance ($520) plus the growth on the available additional savings ($54).

In other words, the net result of paying yourself interest via a 401(k) loan is not that you get a 5% return, but simply that you end out saving your own money for yourself at a 0% return — because the 5% you “earn” in the 401(k) plan is offset by the 5% of loan interest you “pay” from outside the plan. And because you have a 401(k) loan, you also forfeit any growth that might have been earned along the way.

Paying 401(k) loan interest to yourself is really just contributing your own money to your own 401(k) account, without any growth at all.

The net effect? Paying 401(k) loan interest to yourself is really just contributing your own money to your own 401(k) account, without any growth at all.

TAX IMPLICATIONS

One additional caveat of using a 401(k) loan to pay yourself interest is that even though it’s interest and is being contributed into the 401(k) plan, it isn’t deductible as interest, nor is it deductible as a contribution — even though once inside the plan, it will be taxed again when it is ultimately distributed.

Of course, any money that gets invested will eventually be taxed when it grows. But in the case of 401(k) loan interest paid to yourself, not only will the future growth of those loan payments be taxed, but the loan payments themselves will be taxed — even though those dollar amounts would have been principal if simply held outside the 401(k) plan and invested.

Viewed another way, if the saver actually has the available cash to contribute to the 401(k) plan, it would be better to not contribute it in the form of 401(k) loan interest, and instead contribute it as an actual, fully deductible 401(k) plan contribution instead. This would allow the individual to save even more, thanks to the tax savings generated by the 401(k) contribution itself.

Example 3. John decides to take what would have been annual 401(k) loan interest and instead increase his 401(k) contributions by an equivalent amount, grossed up to include his additional tax savings at a 25% tax rate. Thus, instead of paying in just $250 in loan interest to his 401(k) plan — a 5% rate on $5,000 — he contributes $333 on a pre-tax basis, which is equivalent to his $250 of after-tax payments. Repeated over five years, John finishes with $7,434 in his 401(k) plan, even though the account was invested at just 2%, compared to only $6,381 when he paid himself 5% loan interest.

In other words, not only is it a bad deal to pay 401(k) interest to yourself because it’s really just contributing your own money to your own account at a 0% growth rate, but it’s not even the most tax-efficient way to get money into the 401(k) plan in the first place — again, presuming you have the dollars available.

THE NEED ARGUMENT

Ultimately, the key point is simply to recognize that paying yourself interest through a 401(k) loan is not a way to supplement your 401(k) investment returns. In fact, it eliminates returns altogether by taking the 401(k) funds out of their investment allocation, which even at low yields is better than generating no return at all. And using a 401(k) loan to get the loan interest into the 401(k) plan is far less tax efficient than just contributing to the account in the first place.

Of course, if someone really does need to borrow money, there is something to be said for borrowing it from yourself, rather than paying loan interest to a bank.

The bad news is that the funds won’t be invested during the interim, but foregone growth may still be cheaper than alternative borrowing costs, e.g., from a credit card. In fact, given that the true cost of a 401(k) loan is the foregone growth on the account — and not the 401(k) loan interest rate, which is really just a transfer into the account of money the borrower already had, and not a cost of the loan — the best way to evaluate a potential 401(k) loan is to compare not the 401(k) loan interest rate to available alternatives, but the 401(k) account’s growth rate to available borrowing alternatives.

Example 4. Sheila needs to borrow $1,500 to replace a broken water heater, and is trying to decide whether to draw on her home equity line of credit at a 6% rate, or borrow a portion of her 401(k) plan that has a 5% borrowing rate. Sheila’s 401(k) plan is invested in a conservative growth portfolio allocated 40% to equities and 60% to bonds. Given that the interest on her home equity line of credit is deductible, which means the after-tax borrowing cost is just 4.5% assuming a 25% tax bracket, Sheila is planning to use it to borrow, as the loan interest rate is cheaper than the 5% she’d have to pay on her 401(k) loan.

However, as noted earlier, Sheila’s borrowing cost from the 401(k) plan is not really the 5% loan interest rate, which she just pays to herself, but the fact that her funds won’t be invested while she has borrowed. Yet if Sheila borrows from the bond allocation of her 401(k) plan, which is currently yielding just 2%, her effective borrowing rate is just the opportunity cost of not earning 2% in her bond fund, which is even cheaper than the home equity line of credit.

Accordingly, Sheila decides to borrow from her 401(k) plan not to pay herself interest, but simply because the foregone growth is the lowest cost of borrowing for her — at least for the lowest-yielding investment in the account.

When a loan occurs from a 401(k) plan that owns multiple investments, the loan is typically drawn pro-rata from the available funds, which means in the above example, Sheila might have to subsequently reallocate her portfolio to ensure she continues to hold the same amount in equities — such that all of her loan comes from the bond allocation.

In addition, Sheila should be certain that she has already maximized her match for the year — or that she’ll be able to repay the loan in time to subsequently contribute and get the rest of her match — as failing to obtain a 50% or 100% 401(k) match is the equivalent of giving up a 50% or 100% instantaneous return. This would make the 401(k) loan drastically more expensive than just a home equity line of credit, or even a high-interest-rate credit card.

The fundamental point remains: Despite the classic view that 401(k) loan interest is a cost where you are simply paying yourself, the reality is that it’s not a direct cost at all, nor a prospective return. Instead, the true cost of a 401(k) loan is the opportunity cost of not having funds invested to grow — including the risk of losing out on 401(k) matching as well, if applicable — which can actually be an appealing cost relative to other borrowing alternatives for those who need a loan, especially those with credit scores in the 600s or below, who may not have any good borrowing alternatives.

Nonetheless, paying 401(k) loan interest to yourself will never be superior to just investing the money.

So what do you think? Is a 401(k) loan really more akin to an employee receiving a (non-taxable) advance of their 401(k) balance? Do your clients seem interested in 401(k) loans? In what circumstances does it make sense to utilize a 401(k) loan? Please share your thoughts in the comments.