For the same reason Willie Sutton robbed banks, advisors have focused on baby boomers: That’s where the money is. This accepted wisdom is so pervasive that some industry watchers question whether the pendulum has swung too far, at the expense of younger clients getting their financial footing.

The challenge for many advisory firms is that it’s not profitable to do planning for clients who don’t yet have sufficient assets to generate enough AUM fees for the firm. To combat this, advisory firms can adopt various fee-for-service models — from charging minimum fees based on a

Those tactics, however, don’t relieve pressure on the advisory firm to justify the value of its advice. And just because younger clients may have fewer assets and lower net worth, that doesn’t mean they have simple needs. Indeed, there are substantial, complex issues for younger clients, particularly around cash flow.

The planners who succeed with this cohort will be the ones who recognize these individuals’ unique advice needs. As they transition from their 20s to 30s to 40s and beyond, they will have even greater needs for cyclical and ongoing planning advice.

Generations X and Y are still working. As such they may not yet have significant accumulated assets to manage, but they are saving at an increasingly rapid pace — especially the older cohort, as they reach their peak earning years. They also stand to inherit a whopping

But the industry is still struggling with what kind of advice to deliver to these clients that would justify their fees. After all, the mathematical reality of still being early in the accumulation stage is that

In other words, trying to find a few basis points of alpha just doesn’t matter very much for early accumulators; an extra 1% per year of growth may be worth less than just making an extra month of contributions in the first place. This reality tends to lead to relatively straightforward asset-allocated portfolios, and a focus on saving instead. Here planners tend to fall back on that old adage — which doesn’t even require a planner to deliver — “Live within your means, spend less than you earn and save the rest.”

In turn, this approach of doing more simplified financial planning for next-generation clients has in recent years expanded into financial planning software tools themselves, with

The caveat, however, to doing simplified financial planning for next-generation clients in their 20s, 30s, and 40s, is that if you ask them, their financial lives are anything but simple.

After all, it’s throughout the middle decades of the working years that households often face their greatest financial strains, as the series of life transitions that occur through those years come in quick succession, one after another.

By contrast the key transitions faced by a typical retiree are retirement itself, changes brought about by a major health event, and the death of a spouse. These are important to call out because it’s within these moments of transition that financial stress is amplified.

In other words, the occurrence of a transition drives the need for advice and an advisor. And by a measure of life transitions, arguably it’s your next-generation clients who need ongoing planning advice even more than the traditional retiree does.

That’s because retirees may only face a major life transition that could necessitate counsel from an advisor once every decade or so. Meanwhile, next-generation clients face life transitions that could impact their planning needs every year or so.

EBBS AND FLOWS

A key distinction of how the planning process differs for next-generation clients versus traditional baby boomer clients is not merely the pace and nature of life transitions, but the entire focus of the planning process itself.

While baby boomer planning tends to focus on assets — or more generally, on the balance sheet — planning for next-generation clients is more about income and expenses, or the cash flow statement of the household. Most planning decisions for next-generation clients don’t concern where and how to allocate the assets and how to grow them. Instead it’s about where and how to allocate the cash flows of the household’s income, and how to grow that.

After all, every major transition that next-generation clients face has substantial ramifications for the household’s income and cash flows, but not necessarily for their assets. They may be negotiating salary and benefits for a first job, getting married and merging household finances and bank accounts, buying a first home or having children. All of these transitions have implications for where and how to allocate cash flows, and how to grow what’s left over.

In other words, virtually every life transition has a cash flow implication, which in turn necessitates real conversations about the household’s income and cash flows. Just being prepared for these moments — and the conversations they demand — introduces substantial complexity.

Try talking to a new couple about merging their financial lives. Will they be maintaining joint or separate bank accounts? Will they make financial decisions jointly, or delegate them to one person? Will they shift from a dual-income household to a primary breadwinner with a stay-at-home spouse to avoid the cost of childcare?

To put it mildly, these are not simple planning conversations.

Additionally, beyond the life-transition–based cash flow and income issues that may arise for next-generation clients, a sizable number of ongoing planning issues and opportunities in these areas may also emerge. These may include household spending and savings opportunities; managing the debt side of cash flow obligations and building a credit score to be able to access debt; career planning issues that directly impact what a household can earn, from salary benchmarking to negotiating raises or job promotions; going back to school; changing careers; starting a business; or simply maximizing the available employee benefits attached to whatever job is available.

That’s not to mention all the housing decisions that tie not just to cash flow, but also to the interplay between geography and income — e.g., the ability to move to get a better job or a shorter, more manageable commute.

The key point is simply that planning conversations with asset-based retirees revolve around their assets, while planning conversations with income-based workers revolve around their income and where that income flows. A wide array of topical needs and concerns follow these groups, not to mention an ongoing series of life transitions that trigger more specific planning needs and conversations that, unfortunately,

CYCLICAL PLANNING

The

In the traditional planning process with retirees, this monitoring process has revolved primarily around the assets themselves. In part, this is because an ongoing investment management process requires an ongoing monitoring process to ensure that the portfolio remains properly invested and in line with its investment policy statement.

And because typically few transitions occur for clients in the later stages of the accumulation or decumulation processes — short of the retirement transition itself, a health event and the death of a spouse — the only monitoring focus left for asset-based clients tends to be based around monitoring the assets themselves.

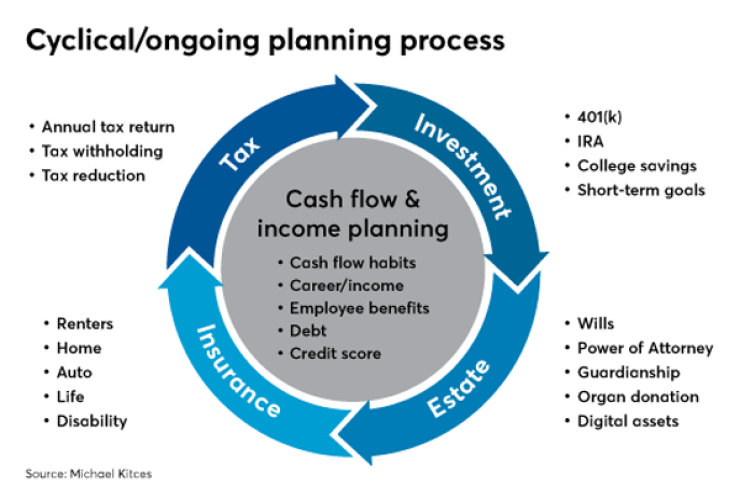

By contrast, when it comes to next-generation clients still in their working years, the ongoing cycle of life transitions means that the whole range of planning needs are more likely to be needed and updated on an ongoing basis — whether it’s insurance, tax, estate or college planning, as well as cash flow and income planning.

In other words, the irony is that planning for next-generation clients and the ongoing complexities that emerge from a never-ending series of life transitions actually make the planning process even more conducive to an ongoing, cyclical advice relationship.

This means the key topics of planning are monitored and regularly revisited, because they are regularly and genuinely changing. Meantime, planning for older clients in later life stages and with fewer life transitions ahead of them takes on a more portfolio-centric focus, simply because there often isn’t anything else left to plan for.

As the chart above highlights, not only are there more (and more regularly changing) topics to discuss with younger clients, but operating on a two-year cycle means a high likelihood that, by the time the cycle fully repeats, some life event or transition may have already happened that necessitates a change to one or more areas. This in turn should be captured in the cyclical planning process.

Meantime, the entire anchor around which the monitoring process occurs is different. In the case of the traditional retired client it’s tied to monitoring the portfolio to make investment changes, while for the younger client it’s primarily focused on income and spending monitoring to address changes in household cash flows.

The key point is that young people with limited assets don’t actually have simpler planning needs. Rather they have a range of complex needs and a number of life transitions that may trigger a desire for financial advice along the way.

There are still many opportunities to charge for planning advice and create value to justify fees. So while there typically may be less aggregate wealth at stake, the focus of planning can shift to the income and cash flows that build wealth — and advisor loyalty — instead.