That advisers should know a client’s tolerance for risk is not a revolutionary idea. Indeed, it’s a requirement of the job — both in the U.S. and abroad. Yet a recent survey of the global landscape for best practices in risk profiling, conducted by Canadian financial planning software provider PlanPlus, reveals a disturbing lack of quality risk tolerance questionnaires (RTQ) and support tools for advisers.

This appears to be driven in part by regulators articulating the principle of knowing the client’s risk tolerance, but providing little guidance on how to do it right. And to a large extent, the problem stems from regulators, academics and advisers themselves not agreeing on exactly what factors of a client’s risk profile should be evaluated.

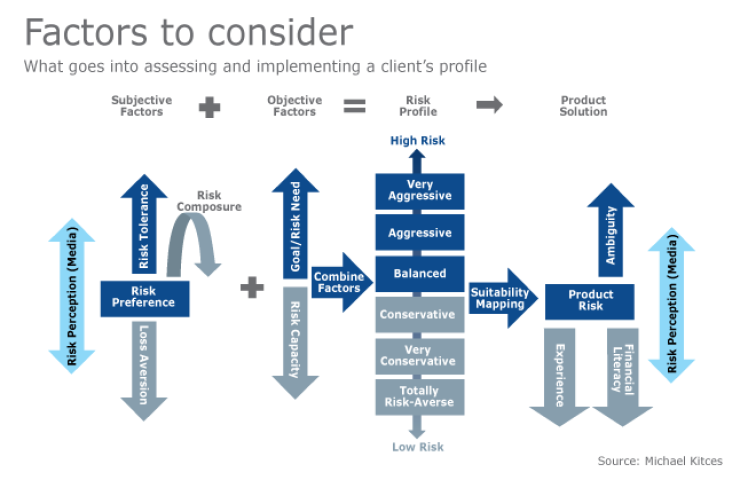

Nonetheless, a growing base of academic research is beginning to articulate a clear risk profiling framework, from recognizing the separation of risk tolerance from risk capacity, the role of risk perception and misperceptions on client behavior, and how risk composure — that is, the stability of a client’s perceptions of risk — can or should vary from one client to the next.

Of course, just because these factors can be identified doesn’t make them easy to measure with a questionnaire, especially when it comes to subjective, abstract traits such as risk tolerance. On the other hand, the research suggests that advisers trying to interview clients about risk may not be doing an ideal job, either.

The optimal approach may eventually be two-pronged: Psychometrically designed risk tolerance questionnaires would assess a client’s willingness to pursue risky trade-offs, and the adviser would then assess the client’s risk capacity, financial goals and ability to achieve objectives given the constraint of risk tolerance. An effective risk tolerance questionnaire may not only make it easier to properly match investment solutions to a client’s needs, but also make it easier to manage a client’s risk perceptions and investment expectations on an ongoing basis — or at least identify which clients are most likely to be challenged when the next bear market comes along.

HUNTING BEST PRACTICES

Assessing a client’s risk tolerance is universally recognized as essential due diligence by regulators around the globe. Notably, though, there’s a wide range of perspectives around what, exactly, risk tolerance actually is, how it should be measured, what factors are and are not relevant, and how those factors should be weighted when evaluating the suitability of an investment recommendation.

-

Clients feel their advisors often recommend products that do not fit their risk profiles.

March 21 -

When advisers blend behavioral finance approaches with data insights, it makes them even more valuable.

September 22 -

Merrill Lynch's Stephen Stabile and others are using behavioral finance tools to make better plans for clients.

October 3

To understand the landscape, the Ontario Securities Commission of Canada engaged

What the researchers found is unfortunate. Most regulators around the world are principles-based in requiring that advisers understand and assess the client’s risk profile — an essential step fulfill any adviser’s know-your-client obligations — yet provide little guidance about how, exactly, that should be done.

An effective risk tolerance questionnaire may not only make it easier to properly match investment solutions to a client’s needs, but also make it easier to manage a client’s risk perceptions and investment expectations on an ongoing basis

Of course, if there were a clear and universally accepted academic framework for evaluating risk tolerance, this might not necessarily be an issue. For instance, in the U.S., an investment fiduciary has an obligation to provide the advice that a prudent expert would have given a similar client in similar circumstances. And although this principles-based, prudent-expert standard isn’t explicitly defined, the courts have recognized it to mean that the expert should follow the principles of the academic Modern Portfolio Theory framework. Yet when it comes to risk tolerance, regulators have placed a principles-based expectation on advisers to make an assessment, albeit without any acknowledgement of the missing academic framework that would/should clarify how advisers actually go about it.

The Canadian researchers found that there’s a surprising paucity of academic research to validate most key concepts associated with a client risk profile. The situation is further complicated by the lack of clear agreement around the factors that should be considered relevant, not to mention how they should be incorporated to make a recommendation. And what little research has been done is difficult to utilize, because there isn’t even a consistent usage of terms regarding risk tolerance and a client’s overall risk profile.

DISSECTING THE RISK PROFILE

From the academic perspective, those who study consumer behaviors around risk and how risk influences investment decisions are converging on three core constructs.

The first is risk tolerance itself. In the academic context, risk tolerance very narrowly and specifically refers to a client’s willingness to take on risk — i.e., to pursue an uncertain positive outcome, with the potential that a negative outcome could result. Those who have greater risk tolerance are more willing to engage in larger risky trade-off scenarios, while those with less risk tolerance tend to avoid them.

Notably, some research in this regard focuses on risk aversion, or the dislike a client harbors toward risk or falling below a certain income/wealth threshold. Ultimately, though, risk aversion can be viewed as the opposite side of the same coin: An unwillingness to take risks is akin to having a high risk aversion.

The second construct is risk capacity, or the client’s financial ability to endure a potential loss, and still be able to achieve his/her goals. Of course, whether goals can be achieved in the event of a bad outcome depends on what the goal is in the first place. And some goals are so aggressive that they may actually necessitate taking on greater risk just to be achievable — which means

-

Risk protection requires holding some investments that underperform when stocks rise, such as government bonds. But the payoff can come when the tide turns.

May 5 -

Advisors in todays crowded field must stand out in order to grow their business. Heres how to build a digital platform that will attract clients.

April 12 -

Unbundling fees might clarify the deductibility of your work, but may be tricky for some firms.

June 15 -

A new model of holistic financial advice is coming on the scene.

May 23

Notably, though, risk capacity and the associated risk needed to achieve a goal

Risk aversion can be viewed as the opposite side of the same coin: An unwillingness to take risks is akin to having a high risk aversion.

Then again, a risky goal for a low-risk-tolerance client implies that it might be time to find a new goal.

The third construct is to recognize that different clients have

For instance, an individual who is highly risk tolerant, but has the perception that a calamitous economic event will cause the market to crash to zero, might still want to sell everything and go to cash. Even though he or she is tolerant of risk, no one wants to own an investment going to zero. Moreover, the research suggests that some people may have better risk composure than others. That is, some investors can keep their cool and maintain a consistent perception of the potential risks around them, while others have risk perceptions that are more likely to swing wildly.

And of course, perceptions of risk themselves also vary by the information that the individual has available to them. Poor financial literacy and education can increase the likelihood of risk misperception, as can media coverage of scary/risky events, triggering the

Notably, risk capacity in this context is an objective measure — the dollars-and-cents mathematical analysis of the consequences of risky events — while risk tolerance and risk perception remain subjective assessments of an abstract psychological trait. And it’s the combination of all those subjective and objective factors that characterize the client’s entire risk profile, which in turn leads to investment recommendations that may vary from very aggressive to very conservative.

Of course, even after evaluating the objective and subjective domains of the risk profile, it’s still necessary to actually map the results of the risk assessment to actual investment solutions, which again entails understanding both the objective risk of the investment product, how it fits into the client’s risk capacity and needs and goals, and also the subjective, perceived riskiness of the investment. Indeed, even an objectively appropriate investment may subjectively seem too risky if the client misperceives or misjudges the risk of the solution.

THE RISK PROFILING TOOLBOX

The good news about our increasingly robust understanding of all the different dimensions of a client’s risk profile is that it allows us to better match investment solutions to client goals, while also being consistent with their tolerance for risk. The bad news, however, is that when there are so many factors involved, it’s difficult to figure out how to blend them all together for an appropriate recommended solution. And that’s saying nothing of sub-factors that are relevant as well. Tolerance for risk based on upside potential, for example, may not mirror downside risk aversion, as

In addition, it’s difficult to measure the subjective aspects of risk tolerance itself, simply because it’s the representation of an abstract psychological trait in the first place. In other words, we can’t just objectively look into someone’s brain and figure out what their risk tolerance is. Instead, we have to ask questions, evaluate the responses and try to figure out how clients feel about their willingness to take risky trade-offs, and how they perceive the risks around them.

Unfortunately, though, many risk tolerance questionnaires (RTQs)

The challenge is greater for younger investors, along with those who have poor financial literacy, because they’re even less capable of making financial self-assessments due to lack of experience, knowledge or both.

To wit, an investor whose portfolio recently ran up from $1 million to $1.2 million may not stress about a subsequent $200,000 loss because they’ve still got their $1 million, and the lost gains were just house money to them. But someone who just inherited $2 million, and who uses the full sum as a reference point, may be far more stressed about a $200,000 loss — even though it’s actually a smaller percentage decline. So an RTQ that asks about the consequences of a $200,000 loss would get somewhat counterintuitive responses, where the wealthier client is more averse simply because of a different reference point for losses.

The situation is further complicated because when we take RTQs, we tend to answer the questions calmly and rationally. When risky events occur, however, we may respond emotionally. Known as the dual-self or

Fortunately, though, while questions such as, “How would you react if the markets declined by X%?” aren’t very effective at evaluating our likely tolerance for risk in real time, it does appear feasible to get at least some understanding of how a particular investor will likely behave in the face of a risky event.

The challenge is greater

For instance, an investor’s risk tolerance, and their likelihood of going to cash in a financial crisis, can at least be partially predicted by their willingness to engage in risky income trade-offs. E.g., “Would you prefer a job with smaller pay increases and more job security, or one with bigger pay increases but less job security?”

In combination, the research suggests that it really is feasible to get some good perspective on an investor’s risk tolerance, and how it may vary from one person to the next. In fact, there is an entire science of psychometrics — the processes for making good tools to measure abstract psychological traits — that can be applied to formulate an effective risk tolerance questionnaire.

Finding a balance is still challenging, though. Neither clients nor advisers

Still, though, the impact of a good risk tolerance questionnaire is striking.

THE SORRY STATE OF RTQs

Looking across the globe, the PlanPlus research team found there were still surprisingly few risk tolerance and risk profiling solutions available for advisers, with only about 10 solution providers of any broad reach. And among those, only 30% were able to document any form of psychometric validity to their risk tolerance questions and process itself, and few were even clear about defining their terminology and focus on what exactly they purported to measure in the first place.

Among the available providers, the researchers characterized them into one of three categories: a.) Comprehensive Risk Profiling tools, which used psychometrically designed questions that were adapted for and mapped to the company’s specific products and services; b.) Subjective Risk-Tolerance-Only questionnaires, which focused solely on effectively measuring subjective risk tolerance, with the idea that it was the adviser’s job to fit the risk tolerance results into the rest of the picture, including risk capacity and financial goals, to make appropriate recommendations; and c.) Asset Allocation Calculators that tended to combine the subjective aspects (risk tolerance) and the objective ones (risk capacity and time horizon) to formulate an asset allocation recommendation.

While arguably any of these can be reasonable approaches, when used appropriately, few of the solutions were clear to even distinguish their limitations. All three types held themselves out similarly as risk tolerance or risk profiling solutions, despite their substantively different approaches, varying degrees of actual psychometric validation of the methodology, and thoroughness of their solution.

For instance, here in the U.S.,

In Canada, where the analysis was based, only 10% of the risk tolerance solution providers have been validated in any way, and only 16% were even considered “fit for purpose” — with the rest either using poorly constructed questions, hopelessly conflated different factors, grossly overweighting a particular factor, or simply had no mechanism to actually identify highly risk averse consumers. And it’s not clear that an evaluation of most risk tolerance questionnaires would fare any better here in the U.S., either.

WHAT COMES NEXT?

The poor state of affairs in risk tolerance questionnaires indicates that there is ample room for improvement.

However, the PlanPlus researchers suggest that there will be little progress until we first get agreement on a common set of terminology and the associated definitions for key terms pertaining to risk profiling. And realistically, this change may have to be driven by regulators, given regulators universally seem to require some kind of risk tolerance assessment process as part of the adviser’s know-your-client obligations. And if regulators aren’t clear about the terminology when writing these requirements, advisers aren’t likely to fill the void.

Ironically, the challenge of getting clearer about the nuances of risk profiling is that as more factors are introduced, it becomes both more difficult to measure them and more complex to determine how to fit them back together and craft an appropriate recommendation. Even relatively simple conceptual adjustments — such as separating risk capacity from risk tolerance — have profound consequences relative to the traditional approach in risk profiling. For instance, when analyzed separately,

Perhaps the greatest challenge in improving the assessment of risk tolerance, though, is simply figuring out what the role of a questionnaire should or should not be.

Many of today’s risk tolerance questionnaires are so badly designed, they may actually be worse than using no questionnaire at all, and/or simply allowing advisers to make their own professional — albeit subjective — assessments. If advisers begin insisting on risk tolerance questionnaires that are actually psychometrically validated as such — and/or regulators require them on their behalf — there may be a breakthrough in the adoption and actual usefulness of risk tolerance questionnaires.

Perhaps the greatest challenge in improving the assessment of risk tolerance, though, is simply figuring out what the role of a questionnaire should or should not be.

Fortunately, getting a good risk tolerance questionnaire doesn’t obviate the need for a good adviser. The PlanPlus authors suggest that the best balance may be to have RTQs focus on just risk tolerance, allowing the adviser to determine the optimal investment solution that incorporates that risk tolerance, along with the client’s risk capacity and financial goals. And because at least some clients may have unusual personal circumstances that don’t fit the normal risk tolerance questionnaire, an adviser should still be expected to identify situations where it’s necessary to override the questionnaire’s findings based on additional factors or nuances.

In fact, regulators around the world, including here in the U.S.,

In the long run, risk tolerance questionnaires and overall risk profiling may be most useful in helping advisers better manage ongoing client relationships. After all, the clearer we are about a client’s true risk tolerance, the easier it is to identify clients who may have risk misperceptions — e.g., the client who really is risk tolerant, but is acting risk averse, and therefore may be over-estimating their actual risk.

And the potential to someday determine how to measure risk composure introduces the possibility of actually knowing in advance which clients are most likely to panic during turbulent markets, and therefore who might need extra education, guidance or hand-holding when the next bear market comes.

At a minimum, the PlanPlus study reveals that while many advisers may be frustrated by the shortcomings of traditional risk tolerance questionnaires, that may not be a failure of the approach of trying to assess risk tolerance, but simply a recognition that there’s still much room for improvement.

So what do you think? Do you find risk tolerance questionnaires to be helpful with clients? If so, what tool do you use? If not, do you think it’s because questionnaires don’t work, or because you haven’t had access to a properly designed one? Please share your thoughts in the comments below.