The bypass trust is a popular estate planning strategy used to reduce a couple's exposure to estate taxes by leaving assets not to the surviving spouse, but to a trust for his/her benefit instead. If the surviving spouse doesn’t inherit the assets directly, he/she is not subject to future estate taxes when the other spouse ultimately passes away.

However, while the bypass trust is effective for saving on estate taxes, it’s not very favorable for income tax planning, given that trusts reach a top 39.6% tax bracket — plus the 3.8% Medicare surtax on net investment income — beginning at just $12,400 of taxable income. And at that threshold, long-term capital gains, as well as qualified dividends, are subject to a whopping 20% + 3.8% = 23.8% tax rate as well. And that’s before applicable state income taxes.

Fortunately, though, the tax rules for bypass trusts and other so-called non-grantor trusts allow for the distribution of income, as well as the tax consequences, to the beneficiaries. This allows those beneficiaries to claim the income on their own personal tax returns and be subject to their far more favorable individual tax brackets. Meanwhile, the trust claims a distributable net income deduction to avoid any double taxation.

Of course, there’s a caveat to passing income from a trust to the beneficiary. While the tactic may minimize income taxes, it compounds the estate tax problem that the bypass trust was designed to avoid by pushing the income back into the spouse’s taxable estate.

Yet given the significant rise in the federal estate tax exemption over the past 15 years — from $1 million in 2001 to $5.45 million today — many bypass trusts are actually no longer necessary. This means that starting deliberately to make income distributions from a bypass trust to the beneficiary has suddenly become a far more effective strategy. For those who may no longer face any estate taxes, it can materially reduce the family’s income tax exposure in the process.

TAXATION OF A BYPASS TRUST

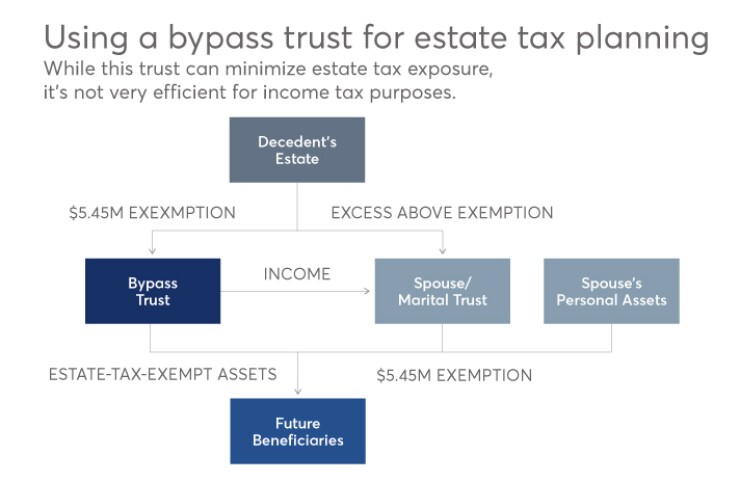

For the past several decades, the bypass trust has been a staple estate planning strategy to minimize estate taxes. The basic concept is relatively straightforward: To avoid crowding all of a couple’s assets into a single person’s name after the death of the first spouse — which could potentially push him/her over the estate tax exemption amount — the spouse who passes away doesn’t actually leave his/her assets to the surviving spouse.

Given the significant rise in the federal estate tax exemption over the past 15 years, many bypass trusts are actually no longer necessary

Instead, the assets go to a bypass trust that can be used for the surviving spouse's benefit, but with enough restrictions such that the assets in the trust bypass the surviving spouse’s estate. That is, they are not included in his/her estate and therefore are not exposed to estate taxes in the future. Consequently, whatever the surviving spouse doesn’t actually spend from the bypass trust can flow estate-tax–free to the future beneficiaries.

While the bypass trust can be very efficient to minimize a family’s estate tax exposure, a significant caveat of the strategy is that it’s not very efficient for income tax purposes. While many types of trusts — e.g., revocable living trusts — are treated as grantor trusts, where the trust’s income is simply reported as income of the grantor, a bypass trust is different.

Because the bypass trust is a separate, standalone entity from the surviving spouse and other beneficiaries for estate tax purposes, it gets treated as a separate income-tax–paying entity as well.

As a result, a non-grantor bypass trust will typically file its own Form 1041 income tax return, reporting its own income (i.e., from the portfolio and other assets that it holds), claiming its own deductions, and paying its own trust tax bill.

Unfortunately, though, the tax obligation on trusts is often higher than the tax obligation of individuals, due to trust tax brackets that are compressed into a fairly narrow income range. While it takes as much as $415,050 for individuals to be subject to the top tax bracket, and $466,950 for married couples, it only takes $12,400 of income for a trust to reach the top 39.6% tax rate.

And notably, reaching the top trust tax bracket also means being subject to the additional taxes that apply for those at higher income levels. This includes the top 20% long-term capital gains and qualified dividend rates, and also the 3.8% Medicare surtax on net investment income. The end result is that at just $12,400 of income, trusts already face a long-term capital gains and qualified dividend rate of 23.8%, and an ordinary income tax rate at 43.4%.

INCOME FROM A BYPASS TRUST

While the standard rule is that a non-grantor trust must report and pay taxes on any income it receives, a trust that makes distributions to trust beneficiaries may pass along the income tax consequences of its income to those underlying beneficiaries as well.

Specifically, a non-grantor trust that makes income distributions to beneficiaries will pass through that income to the underlying beneficiary, who reports it on his/her own personal tax return instead. The character of the income (e.g., ordinary taxable vs. tax-exempt bond interest vs. qualified or non-qualified dividends) remains the same in the hands of the beneficiary. Any expenses associated with the income — such as an investment management fee for managing the property that produced the income — are passed through to the beneficiary as well. If only a portion of the trust’s total income is distributed, that pro-rata portion of the taxable income and deductible expenses go along with it. If there are multiple beneficiaries, then each beneficiary receives their own pro-rata share.

-

Given retirees’ unease about the future, spending down principal can prove a curious challenge.

August 24 -

These planning strategies can prevent beneficiaries from biting off too much — or too little.

August 19 -

Knowing how and when to withdraw can save clients big in their golden years.

August 9

Example 1a. Betty is the beneficiary of a $1 million bypass trust that was established for her by her late husband Donald. This year, the trust generated $47,000 of income, including $12,000 of qualified dividend income and $35,000 of taxable bond interest. In addition, the trust had an asset management fee of $7,000. During the year, the trust made $2,000 monthly distributions to Betty to maintain her standard of living. In addition, the trust also made a $5,000 one-time distribution from income to Betty’s son Ralph for his education — which was permissible under the terms of the trust.

Ultimately, Betty received $24,000 of distributions, which constitutes 51.06% of the trust’s total income. As a result, she will report $6,128 of qualified dividend income (51.06% of the $12,000 total), $17,871 of the bond interest, and $3,575 of the management fee deduction, all of which are claimed on her own individual tax return, at her own individual tax rates. The dividends are still eligible for qualified dividend treatment, the bond interest is still taxable as ordinary income and the investment management fee deduction will be claimed accordingly.

Similarly, Ralph’s $5,000 income distribution, which is 10.64% of the total trust income, will be reported as $1,277 of qualified dividend income, $3,724 of taxable bond interest and a $745 deduction for investment management fees.

Distributing the trust’s income so it can be claimed on their personal tax returns, and reducing the trust’s taxable income to $0 thanks to the DNI deduction, can result in significant income tax savings.

An important caveat: The income distributed in this pass-through way, from a trust to the beneficiaries, will potentially be taxed twice — once at the trust level, and again in the hands of the beneficiary when it passes through.

To avoid this outcome, trusts are permitted to claim an

Example 1b. Continuing the prior example, the fact that the trust paid out $29,000 of income distributions, including $7,405 of qualified dividends and $21,595 of taxable bond interest, means the trust will receive a $29,000 DNI deduction. As a result, the trust will only report income taxes on the remaining $18,000 of undistributed trust income, claiming the remaining $2,680 of undistributed investment management fee deductions. In the extreme, if the trust had distributed all of its income, it would have distributed all of the associated income tax consequences as well, and the DNI deduction would reduce the trust’s taxable income all the way to zero.

From the tax reporting perspective, it’s important to recognize that even with the DNI deduction, a bypass trust must still report the income on its Form 1041 trust tax return. However, the DNI deduction effectively offsets that income, producing a net income (and therefore a net tax liability) of $0, while the pass-through of the income to the underlying beneficiaries — reported on Form K-1 — means that the beneficiaries claim the income tax consequences on their personal tax returns instead, and owe taxes based on their own tax brackets.

From the tax planning perspective, those individuals already in the top tax brackets will not necessarily benefit, but for the overwhelming majority of people who are in lower tax brackets, distributing the trust’s income so it can be claimed on their personal tax returns, and reducing the trust’s taxable income to $0 thanks to the DNI deduction, can result in significant income tax savings by shifting the income away from the trust’s compressed tax brackets and into the beneficiary’s more favorable tax rates.

DISTRIBUTING AND DEDUCTING

Unfortunately, passing through capital gains from a trust to the underlying beneficiaries — and their individual tax brackets — is more complicated than with other forms of taxable income such as interest and dividends.

By default, under the

And if the trust allows capital gains to be treated as income,

The significance of this treatment is twofold. First, capital gains are treated as principal for accounting purposes, which means that even if the trust states that all income should be distributed to the beneficiary, the income will only include interest and dividends and not the capital gains — which are considered taxable income but not accounting income. And since the capital gains are not distributed to the beneficiary, the tax consequences are not distributed either, which means the capital gain will remain taxable to the trust, at the trust’s tax rates.

Furthermore, if capital gains are allocated to principal and the trustee doesn’t have the discretion to adjust the treatment of principal and income — even if the trust makes a principal distribution of actual dollars — the taxable capital gains and associated tax consequences still do not pass through to the beneficiary and there is still no DNI deduction.

Thus, for a trust document that does not allow for capital gains to be treated as income, nor provides the trustee any discretion to treat capital gains as income, the capital gains will effectively be stuck in the trust, at the trust’s tax rates — which as noted earlier, quickly reach 20%, plus the 3.8% Medicare surtax at the top tax bracket of only $12,400 of income.

This suggests that for tax purposes, it is more favorable for a bypass trust to treat capital gains as income for accounting purposes — which makes it possible for the trustee to distribute them for tax purposes —and/or to at least give the trustee discretion to adjust the income/principal treatment of capital gains.

The DNI deduction is only available if dollars actually are distributed from the trust to the beneficiary.

Such provisions, however, should be weighed carefully, as what may be appealing for income tax purposes and the income beneficiary may be detrimental to the remainder beneficiary, who may not be so happy that all the trust’s growth was paid out of the trust and will not be received by that remainder beneficiary. Trustees still have an obligation to balance the interests of both income and remainder beneficiaries.

DISTRIBUTIONS FROM BYPASS TRUSTS

While a bypass trust can receive a DNI deduction for passing through income to an underlying beneficiary, the DNI deduction is only available if dollars actually are distributed from the trust to the beneficiary. If no distributions occur, and there were no distributions required to occur, then no tax consequences pass through, and there will generally be no DNI deduction, either.

In the context of a bypass trust, whether distributions occur is not automatic. In some cases, a bypass trust will stipulate that all income be automatically distributed annually to a surviving spouse or other beneficiary.

However, this is not common; after all, if the whole point of the bypass trust is to keep assets left to the trust out of the surviving spouse’s estate, mandating distributions to the spouse isn’t very helpful, as it just drives the growth of the bypass trust back into the estate it was meant to avoid.

More commonly, a bypass trust instead allows distributions to the beneficiary made at the discretion of the trustee, typically based on an ascertainable standard like distributions of income and/or principal for health, education, maintenance and support. And it’s up to the trustee to decide whether and how much to distribute to the beneficiary under this discretionary standard. The trustee may also have discretion to determine whether capital gains are treated as income or principal, depending on the terms of the trust document.

For a trust to fully distribute its taxable income and the associated tax consequences to a beneficiary, the trustee will often need to exercise discretion to make those distributions, and to treat capital gains as income to be part of those distributions. Even if the trust mandates income distributions, the trustee may still need the discretion or direct guidance from the trust document to treat capital gains as income and pass those through as well. And if the trust doesn’t compel income distributions at all — which is more common — then it’s entirely up to the trustee’s discretion to make sufficient distributions in the first place, to actually pass through at least the “income” portion of the trust and its associated tax consequences.

THE BALANCING ACT

Income tax planning for bypass trusts is important because a bypass trust generating, and retaining, taxable income can be highly unfavorable, due to the compressed trust tax brackets that trigger 23.8% tax rates on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends, and 43.4% tax rates on interest and other ordinary income, at just $12,400 of taxable income. Of course, state income taxes can potentially pile up on top, too.

Thus, to the extent the trust beneficiaries are in a lower tax bracket — which may be true even if they have far more total income, because the individual and married tax bracket thresholds are so much more favorable — distributing bypass trust income to the beneficiaries, to report at their lower tax rates while claiming the DNI deduction for the trust, can generate significant family tax savings. The benefit can be slightly reduced, however, if the beneficiary has lower federal tax brackets but is subject to a higher state income tax rate.

On the other hand, the whole reason for a bypass trust is to avoid having those assets — and their subsequent growth — included in the estate of the surviving spouse beneficiary.

If a bypass trust systematically distributes all of the trust’s income into the hands and estate of a spouse who is over the federal estate tax exemption already — or who crosses over the exemption because of those distributions — those distributions may be subject to lower income tax rates, but will ultimately face a 40% federal estate tax rate. This can ultimately cause the family to finish with even less wealth in the long run, having lost far more in estate taxes than was saved in shifting income tax consequences from the trust to the beneficiary.

Example 2. Betty has a personal net worth of $7 million, which includes a portfolio generating $150,000 of annual income, and is the beneficiary of her husband’s $4 million bypass trust that last year generated $120,000 of income. If Betty were to pass away today, her taxable estate would already exceed the current $5.45 million estate tax exemption, with the excess subject to a 40% federal estate tax. Betty is currently in the 28% tax bracket as a single, widowed individual, and distributing the trust’s income to her would cause it to be taxed at a blend of the 28% and 33% tax brackets, which is far more appealing than the trust’s 39.6% tax bracket — in addition to avoiding some 3.8% Medicare taxes on net investment income. However, the potential to save up to 11.6% in income taxes is overshadowed by the fact that the income, once in Betty’s name, may face a 40% estate tax in the future, causing the family to finish with even less money than just paying the income taxes at the trust level and keeping the income out of Betty’s estate.

Even if the surviving spouse beneficiary of the bypass trust is below 2016’s federal $5.45 million estate tax exemption, there’s still the possibility of state estate taxes applying in nearly a dozen states. For some states, the exemption limit is the same $5.45 million, which means driving assets into the surviving spouse’s estate can result in a whopping 56% estate tax (40% federal plus 16% state rate). In other states, the exemption is lower. At a $1 million state exemption level, a surviving spouse with $2 million of net worth would have no federal estate tax exposure, but would still face a 16% state estate tax in the future on trust distributions received, in addition to the income tax consequences.

On the other hand, over the past 15 years, the federal estate tax exemption has climbed from $1 million to $5.45 million, and only a

In the past it may have been preferable to keep the income in the trust to avoid the beneficiary’s estate tax rates, without any estate tax exposure. But now it’s more appealing to distribute the income to take advantage of the beneficiary’s income tax rates. Trustees should, however, still be cognizant of whether it’s appealing to keep income in the trust for non-tax reasons, such as restricting access to the funds for a financially irresponsible beneficiary, or for asset protection purposes.

At a minimum, though, the rise of the estate tax exemption means that distributing income from a bypass trust to a beneficiary has become far more desirable than it was in the past. This is due to the number of beneficiaries who are not actually exposed to estate taxes and no longer need the bypass trust, and could save on income taxes by shifting the income from the trust to the beneficiary. However, for estates that do still face future federal or state estate tax exposure, or are concerned about the spendthrift, asset protection or other benefits of a bypass trust, the final decision may actually be to keep the income in the trust anyway, and just pay the unfavorable tax rate.

So what do you think? In your efforts to limit your clients’ tax exposure, have you favored one trust tactic over another? Please share your thoughts in the comments below.