Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

When it comes to retirement accounts and taxes, the question isn’t so much whether income tax will need to be paid, but rather, when income tax will need to be paid.

Accordingly, solid tax planning generally means trying to accelerate the taxation of income that would otherwise be taxable in future years into the current year when a taxpayer’s marginal tax rate is relatively low, and to use accounts such as Roth IRAs, Roth 401(k)s, and Roth 403(b)s.

This can be accomplished in a variety of ways, e.g.,

Typically, it makes sense to use traditional retirement accounts, such as traditional IRAs, 401(k)s, and 403(b)s, to defer or reduce income in years a taxpayer will pay a relatively high marginal income tax rate. Of course, when marginal rates are relatively high, accelerating the taxation of income into the current year when it would otherwise be taxed in the future, and at a potentially much lower rate in that future year, rarely makes sense. Accordingly, the last thing a taxpayer would want to do in most of those situations would be to make a Roth conversion!

Note that I said In most of those situations — but not all.

Why? Because even in high marginal tax-rate years in situations where a traditional IRA contains both pre and after-tax dollars, it can be beneficial to make partially taxable Roth conversions — or, in certain situations, tax-free Roth conversions — provided an individual’s after-tax dollars make up enough of the IRA.

Getting after-tax dollars into IRA accounts

Distributions from traditional IRAs are typically fully taxable because the distributions most often consist entirely of never-before taxed income — either contributions for which a tax break was received when those contributions were first made or for earnings on those amounts.

Sometimes, however, a traditional IRA will contain some amount of after-tax dollars on which taxes have already been paid. Such after-tax dollars can find themselves in a traditional IRA in one of two ways: through nondeductible IRA contributions or through the rollover of after-tax dollars from employer plans, which had received nondeductible contributions at some point in the past.

After-tax dollars in IRAs are often the result of one or more nondeductible contributions made to a traditional IRA.

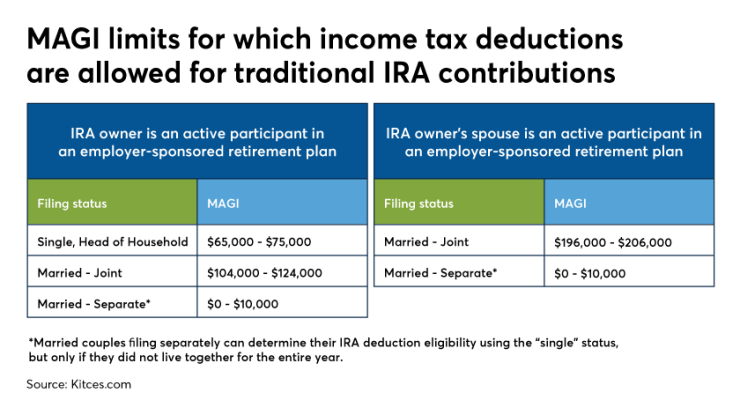

As while an above-the-line deduction is generally allowed for any contribution to a traditional IRA, if the IRA owner and/or their spouse is an “active participant” in an employer-sponsored retirement plan (including defined contribution and defined benefit plans, and SEP or SIMPLE IRAs)andthe IRA owner’s modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) exceeds certain amounts, the ability to deduct the IRA contribution is reduced or eliminated altogether.

Notably, it’s not the ability to make the traditional IRA contribution that is phased out; rather, it’s thedeductibilityof that otherwise allowable contribution.

Accordingly, if an individual chooses to make a traditional IRA contribution but is not able to deduct the full value of the contribution (because of the combination of their income and/or their spouse’s status as an active participant in an employer plan), then some or all of the contribution will create basis (after-tax amounts) inside the traditional IRA.

After-tax amounts rolled over from employer-sponsored plans

After-tax amounts can also make their way into a traditional IRA if they are rolled over from an employer-sponsored retirement plan. More specifically, employer-sponsored retirement plans can give participants the opportunity to make nondeductible after-tax contributions to the ‘traditional side” of the employer-sponsored plan, provided total contributions to the participant’s account — the after-tax contributions, plus the employee’s salary deferrals, plus employer contributions — do not exceed the IRC Section 415(c)

Traditional IRA balances subject to pro rata rule

After-tax dollars inside traditional IRAs represent money that has already been taxed. Thus, when those after-tax dollars are distributed, they represent a nontaxable return of basis.

Unfortunately for IRA owners, though, there is no way to “reach in” to their IRAs and distribute only the after-tax dollars tax-free. Rather, distributions made from traditional IRAs with both pre and after-tax dollars are subject to what is known as the “pro rata rule.”

Simply put, the rule says that when a distribution is made from a traditional IRA that contains both pretax and after-tax dollars, the distribution will consist of a ratable (proportionate) amount of each. So, for instance, if a traditional IRA consists of 20% after-tax dollars and 80% pretax dollars, then each dollar distributed — including distributions made as a part of a Roth conversion — will generally consist of 20% after-tax dollars and 80% pretax dollars.

Example 1: Adam is the owner of a traditional IRA that has a total balance of $200,000. Over the years, he has made a total of $30,000 of nondeductible contributions with after-tax dollars to the IRA.

Thus, a total of 15% ($30,000 ÷ $200,000) of each distribution Adam makes will consist of a return of his after-tax contributions, while the remaining 85% of each distribution will consist of taxable (pretax) dollars.

Accordingly, if Adam takes a distribution of $20,000 from his IRS, he can’t just take $20,000 of his $30,000 of after-tax contributions on a tax-free basis. Instead, $3,000 ($20,000 x 15%) will be a tax-free return of his after-tax contributions, and the remaining $17,000 ($20,000 – $3,000) will be taxable. That leaves Jack $27,000 ($30,000 – $3,000) of nondeductible contributions still inside of the IRA.

Additionally, it’s important to realize that the pretax and after-tax portions of a pro rata IRA distribution are, in essence, stuck together. That’s unlike pro rata distributions from 401(k) and similar plans, which, pursuant to

Example 2: Recall Adam, from the previous example, whose $200,000 IRA balance includes $30,000 (15%) of after-tax funds. As before, he takes a distribution of $20,000 from his IRA funds which comes to, per the rule, $3,000 of after-tax funds, and $17,000 of pretax funds.

But if Adam opts to have $3,000 of that distribution converted to a Roth IRA and rolls the remaining $17,000 back to a traditional IRA in an effort to convert the $3,000 of after-tax and none of the pretax dollars, he cannot choose to allocate the $3,000 of after-tax dollars to just the Roth IRA conversion, thereby making it tax-free.

Rather, 15% of the $3,000 Roth conversion, or $450 will be a tax-free conversion of after-tax dollars, while the remaining $2,550 will be pretax dollars.

Similarly, of the $17,000 rolled back to a traditional IRA, $2,550 will represent after-tax dollars put back into the account, while the remaining $17,000 will be pretax dollars.

Roth: To convert or not to covert

In general, the decision is one driven by

That calculus, however, can be changed by the presence of after-tax dollars in an individual’s retirement account. Simply put, the greater the percentage of after-tax dollars in the account (that is, consisting of contributions made for which tax deductions werenot taken) the more makes sense it makes to convert all or a portion of the account now, even if today’s marginal tax rate is higher — and in some cases, substantially higher — than is expected to be the case in the future.

But why pay tax now, at a higher rate, when you can wait and pay taxes in the future at a lower rate?

In a word: earnings.

If after-tax amounts are converted to a Roth IRA, the future earnings will be tax-free.

Recall that if after-tax amounts are converted to a Roth IRA, the future earnings will be tax-free, provided the qualified distribution rules have been met.

And when a conversion is made from an IRA containing both pretax and after-tax dollars, for every $1 of taxable income generated due to the conversion — (withdrawing pretax funds from the traditional IRA to deposit into the Roth IRA — there is future tax-free growth in the Roth IRA on some amount greater than $1, where the exact amount depends on the ratio of pretax-to-post-tax dollars in the IRA account!

Example 3: Wendy is a 40-year-old IRA owner with an $80,000 IRA balance. She is currently in the 35% income tax bracket and expects to have a marginal income tax rate of closer to 25% in retirement. She is a diligent saver, has other assets, and hopes to avoid taking distributions from her retirement accounts until she is 70 years old.

The projected decline in Wendy’s projected marginal rate between now and retirement would usually be a strong contraindication for making a Roth conversion now. But suppose that, of the $80,000 balance in her traditional IRA, 40% of that balance, or $32,000, consists of after-tax dollars. That additional information should materially change the thought process.

Why? Think about what would happen if Wendy does not convert, and follows through on her plan of not touching her IRA funds until she is 70 years old. Ignoring any future contributions Wendy might make, if she were able to achieve a 7% annual rate of return on her current $80,000 balance, she’d have just under $609,000 in her traditional IRA at age 70. Despite the sizable increase in total account value, though, only $32,000 — her current amount — would represent after-tax funds that will ultimately be distributed tax-free.

Meanwhile, as shown in the chart, over the 30-year period, taxable earnings of more than $211,000 will have accumulated that are attributable to the $32,000 of present-day, nontaxable after-tax funds in Wendy’s traditional IRA.

Consider, however, what would happen if Wendy bucked conventional wisdom and converted today, at her higher marginal income tax rate.

True, she’d be paying a higher income tax rate on the taxable $48,000 of the conversion than she’d otherwise have in retirement, but only 60% of the total $80,000 conversion balance would be taxable!

Meanwhile, Wendy would enjoy tax-free growth on the entirety of the converted amount.

Stated differently, for every $1 of pretax money converted today — for which Wendy will owe income tax at her present high income tax rate — 67 cents ($0.67 is 2/3 of $1, reflecting the proportion of 40% of after-tax and 60% of pretax funding in the account) of “bonus” after-tax money will be dragged along into the Roth IRA, too. And once there, the earnings on the full $1.67 will be tax-free.

So, the key question for Wendy, and clients in similar situations, becomes: Is it worth it to pay ordinary income tax on $1 today to have tax-free growth on $1.67?”

Notably, there is no magic threshold or ratio that makes a conversion right or wrong for all clients, all the time. it’s not as simple as saying, “If at least 20% (or 30%, 40%, etc.) of an IRA is after-tax money, then it should be converted to a Roth IRA.”

Rather, each client’s situation must be evaluated separately, taking into consideration not only the ratio of pretaxto-after-tax dollars in the IRA, but also the expected difference between the current and the future marginal income tax rates — the lower the potential difference, the more a conversion today makes sense — and the length of time until the after-tax amounts would otherwise be distributed.

Of course, in situations in which there is either an extremely high percentage of pretax dollars or after-tax dollars in a traditional IRA, the decision-making process is significantly simplified.

For example, if a traditional IRA contains 99% pretax dollars and just 1% of the funds are after-tax, the “convert to Roth or not” equation is not really impacted. One percent of a conversion tax free just isn’t enough to move the needle, and the decision will be driven as normal by evaluating current versus future tax rates — and converting to a Roth whenever the tax rate will be lower.

On the other hand, if a traditional IRA were somehow comprised of 99% after-tax dollars and only 1% pretax dollars, it’s as close to a no-brainer “convert” decision there is, regardless of how much higher today’s marginal income tax rate is compared to the projected future marginal rate, as nearly all of the growth will simply be converted from taxable to tax-free.

Isolating basis using roll-ins into employer plans

But what if there was a way to reduce only the amount of pretax dollars in a client’s traditional IRA, in a way that makes the Roth conversion decision much easier, because afterward a greater percentage of the IRA would be comprised of after-tax dollars?

While not every client will have such an opportunity, for many clients, there is a way in which financial advisors can help them do just that.

More specifically, clients may be able to increase the percentage of the after-tax dollars in their traditional IRA by completing a partial rollover of IRA funds into an employer-sponsored retirement plan, or by using qualified charitable distributions (QCDs).

In both instances, an exception applies to the pro rata rule, enabling the distribution to consist of entirely pretax funds — leaving a greater percentage of after-tax funds behind.

For some lucky retirement savers with access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan, the complications of the IRA pro rata rule can be completely eliminated. If the plan allows participants to roll in “outside’”(non-plan) funds, the taxpayer can take advantage of a glitch in the Internal Revenue Code matrix.

More specifically, while the pro rata rule generally applies to IRA distributions (including amounts being rolled over), after-tax amounts are not eligible to be rolled from IRAs into employer-sponsored retirement plans. Accordingly, when distributions from a traditional IRA are rolled into an employer-sponsored retirement plan, the IRS treats the rollover as consisting entirely of pretax dollars, to the extent such funds existed as pretax dollars in the traditional IRA in the first place, because the after-tax dollars aren’t allowed to come along for the rollover ride even if they wanted to.

Using this tactic, an IRA owner can essentially vacuum out their pretax IRA dollars, leaving only their after-tax IRA dollars behind in the IRA. Those remaining after-tax dollars can then be converted, tax-free, to a Roth IRA once all the pretax dollars have been safely sequestered inside of an employer retirement plan.

Example 4: Ben is an IRA owner who is also a participant in a 401(k) plan that allows rollovers into the plan. His total IRA balance is $350,000, $40,000 of which are after-tax contributions.

Ben is currently in the 24% ordinary income tax bracket, and he expects to be in the 12% income tax bracket in retirement. As such, an IRA-to-Roth IRA conversion would generally be inadvisable at this time.

Ben, however, can take advantage of his 401(k)’s provision allowing rollovers into the plan and the exception to thepro rata rulethat IRA-to-plan rollovers enjoy.

More specifically, Ben can rollover the entire account balance less after-tax contributions, for a total of $310,000 ($350,000 – $40,000), from his traditional IRA, which represents the total of pretax funds accumulated in the account.

Although such a distribution would normally be treated as consisting of a ratable amount of pretax and post-tax dollars, since the rollover destination is Ben’s 401(k), and after-tax dollars are not allowed to be rolled into such accounts, theentire$310,000 amount will be treated as consisting of pretax dollars.

And with $310,000 of pretaxfunds siphoned out of the Ben’s IRA, the $40,000 left will consist entirely of after-tax dollars, which can then be converted to a $40,000 Roth IRA, which is a tax-free conversion since all of the remaining IRA dollars are entirely after-tax.

Dodging pro rata rule complications when returning pretax dollars to the traditional IRA

Many times, retirement savers like the idea of isolating their traditional IRA basis via rolling their pretax dollars into an employer-sponsored retirement plan, often for purposes of a Roth IRA conversion, but sometimes just to distribute from the traditional IRA tax-free. But they don’t really want to keep the rolled-in funds in the plan. Rather, for a variety of reasons, e.g., expanded investment options, more flexible distributions provisions, etc., they prefer to somehow get those funds back into an IRA.

Fortunately, in many situations, this is possible — provided the individual waits the appropriate amount of time.

The first caveat is simply that to roll the dollars from the employer retirement plan back to the IRA, the plan participant must be permitted to take dollars out of the 401(k) plan in the first place. If a plan participant has already separated from service, distributions from the employer-sponsored plan are generally allowed. Whether a participant who is still working for the company sponsoring the plan will be allowed to take an in-service distribution is ultimately a plan-level decision; however, most plans that allow rollovers into the plan will allow those same rollovers to be distributed back out of the plan at the participant’s discretion.

To avoid pro rata rule complications, though, this option (to roll the funds rolled-in to an employer-sponsored retirement plan back out at any time) cannot be exercised until the calendar year after the left-behind-after-tax-IRA funds are converted to a Roth IRA.

This is necessary because the pro rata rule ultimately calculated on IRS Form 8606,Nondeductible IRAs, uses the year-end traditional IRA balance.

As such, rolling pretax funds out of an employer-sponsored retirement plan and into a traditional IRA in the same calendar year as an IRA-to-Roth IRA conversion will cause those plan-to-IRA rolled-over pretax funds to be included in the IRA pro rata rule used to calculate the tax-free portion of the IRA distribution that was converted to a Roth IRA earlier in the year!

By contrast, rolling funds out of an employer plan and into a traditional IRA in the calendar year after an IRA-to-Roth IRA conversion is completed (or anytime thereafter) will not cause the same complications.

Example 5: Recall Ben, from the previous example, who rolled the $310,000 in his traditional IRA to his 401(k) plan in order to isolate the $40,000 of after-tax money in his IRA to complete a tax-free Roth conversion in March of this year.

Now let’s suppose that Roth conversion was subsequently completed on Sept. 1, 2020 and, further, that Ben, unaware of the pro rata complications outlined above, rolls the $310,000 back out of his 401(k) and to histraditional IRA on Dec. 1, 2020.

Despite the fact that there were no pretax dollars in Ben’s IRA at the actual moment of his September 2020 Roth conversion, the $310,000 ofpretaxmoney in histraditionalIRA at year-end (assuming no gains/losses) will be included in the pro rata calculation of that distribution.

Accordingly, only $40,000, or 11.43%, of Ben’s Roth conversion will be tax-free, meaning that of the original $40,000, only $4,572 will be considered tax-free with the remaining $35,428 being taxable.

If, on the other hand, Ben had waited just one additional month, and completed the same rollover in January 2021 (the calendar year after completing his IRA-to-Roth IRA conversion in December 2020), the entire conversion would have been a tax-free conversion of after-tax funds.

Sometimes, timing really is everything.

Notably,

Thus, while distributions of after-tax funds from an employer-sponsored retirement plan are still technically eligible to be rolled into a traditional IRA, that should no longer be done. Instead, IRS Notice 2014-54 allows those amounts to be separated out and rolled over separately. Consequently, such amounts should be rolled over into a Roth IRA, effectively engaging in a tax-free Roth conversion and allowing future growth to be (potentially) tax-free as well, instead of having future growth still being taxable, as would be the case if it were rolled into a traditional IRA.

Using QCDs to increase the percentage of after-tax dollars in an IRA

As discussed above, the most effective way for retirement savers to isolate basis in a traditional IRA is by rolling the pretax portion of the account into an employer-sponsored retirement plan when possible. Unfortunately, that’s simply not an option for most savers either because they don’t participate in an employer-sponsored retirement plan or because the plan that they do participate in does not allow rollovers into the plan.

For savers who lack this option but are at least 70 ½ or older, another way to increase the percentage of after-tax dollars in a traditional IRA is

QCDs are relevant in this context because, while the pro rata rule generally applies to distributions from IRAs, QCDs are deemed to be made from only the pretax portion of an individual’s IRA balance.

More specifically,

"In determining the extent to which a distribution is a qualified charitable distribution, the entire amount of the distribution shall be treated as includible in gross income without regard to subparagraph (A) to the extent that such amount does not exceed the aggregate amount which would have been so includible if all amounts in all individual retirement plans of the individual were distributed during such taxable year (emphasis added)and all such plans were treated as one contract for purposes of determining under section 72 the aggregate amount which would have been so includible. Proper adjustments shall be made in applying section 72 to other distributions in such taxable year and subsequent taxable years.”

As a result, someone with only a limited amount of pretax dollars in a mostly after-tax IRA could siphon off some or all of the pretax dollars with a QCD, and then — similar to the rollover to an employer retirement plan strategy, do a Roth conversion on the remainder of what would only be after-tax at that point.

Alternatively, even just reducing the portion of an account that has a mixture of pre and after-tax dollars by using QCDs for at least some of the pretax dollars can make Roth conversion math more appealing.

Example 6: Patty is 73 years old and owns a small IRA. Her total IRA balance is $35,000, $14,000 of which consists of after-tax funds. In an average year, Patty, who is in good health, gives $4,000 to various charities, including her house of worship.

Suppose that instead of giving just $4,000 to her charities of choice this year, Patty uses a QCD to make her contributions for 2020 and the next three years. Thanks to the exception to the pro rata rule that QCDs enjoy, the $16,000 ( 4 x $4,000) of charitable contributions will come entirely from Patty’s pretax IRA dollars.

Thus, after the QCD, her IRA account balance will be $35,000 (the original IRA balance) minus $16,000 (pretax distribution to charity), leaving her with $19,000, of which $5,000 will remain pretax and $14,000 of which will still be tax-free.

Even though Patty would still have some pretax money in her IRA ($19,000 – $14,000 = $5,000), the percentage of after-tax dollars in her IRA will have jumped from just $14,000 ÷ $35,000 = 20%, to roughly $5,000 ÷ $35,000 = 74%.

Limitations of using QCDs to isolate nondeductible basis of traditional IRAs

Using QCDs to isolate or increase the percentage of basis in an IRA has two notable drawbacks compared to isolating basis via a rollover to an employer-sponsored retirement plan.

First, while there is no limit on the amount of pretax dollars that can be rolled from an IRA to an employer plan,when the plan allows rollovers into the plan, QCDs are limited to no more than $100,000 annually.

Second, and probably a bigger issue for most, a rollover from an IRA to an employer plan is merely a cosmetic change when it comes to an individual’s accounts — assets are simply being relocated from one account to another with no change in ownership taking place.

By contrast, when an individual makes a QCD, the QCD amount is ‘lost’ to charity because it really is a charitable donation.

Thus, while using QCDs to help isolate basis can be an effective strategy for the charitably inclined client, particularly when an individual is willing to be flexible with their gifting schedule, for those savers with little or no charitable goals, it’s not a viable strategy as giving away, even pretax dollars, is always more “expensive” than paying the tax on converting them.

The ultimate takeaway here is that while Roth IRA conversions should generally be made when an individual is in a low marginal tax bracket — if the percentage of after-tax dollars in that individuals IRAs is high enough either organically or as a result of taking advantage of one or more basis isolating techniques — a Roth IRA conversion can make sense regardless of the tax rate that must be paid on the pretax portion of the conversion.

Jeffrey Levine, CPA/PFS, CFP, MSA, a Financial Planning contributing writer, is the lead financial planning nerd at