After being diagnosed with a brain tumor, fighting in arbitration with a fellow advisor and their employer, Commonwealth Financial Network, and

The cost was worth it, he said. Womack accused Commonwealth and the other advisor, with whom he worked closely, of collaborating to thwart a succession plan for his practice and taking over his book of clients. Commonwealth, Womack alleged in FINRA arbitration, defamed him by falsely telling his customers that he had made misrepresentations about the credit quality of bonds held by "an elderly client" and in a state unemployment benefits claim, along with violating email and text messaging guidelines.

"I was willing to pay almost any amount of money to clear my name and record to continue to show my clients that I have served them with integrity for over 14 years," Womack said. His email interview with Financial Planning is the first time he's spoken publicly about the March

Representatives for Commonwealth said the firm followed the rules in Womack's case — a type familiar to advisors and other industry experts versed in the lengths that some independent wealth managers can go to claw back business from a departing team.

The moniker "independent" refers to financial advisors employed as 1099 contractors by firms such as Commonwealth and rivals including Cambridge Investment Research and LPL Financial. That channel of wealth management, which is the opposite of advisors who are employed directly on W-2 basis, offers most advisors greater flexibility and pay with the benefit of owning their own business.

Independence in wealth management runs on a spectrum, ranging from firms that require contractors to run their practices according to certain business models and to sell proprietary products to those that leave almost everything for advisors to decide as they see fit. The perks of being independent include the increased compensation and an ecosystem of custodians, technology firms and other vendors competing to serve advisors' practices. Enticed by the promises of independence and the marketing efforts behind them, advisors routinely expect that owning their business will give them the ability to leave one wealth management firm and sign on to another without interference or harassment from a former employer. But some advisors who decide to leave their brokerages in a quest for better service or more varied investment products for clients find that the trappings of independence can vanish quickly.

For example, former branch managers with another independent brokerage, Securian Financial Services, say the firm's promise of "independence with a hug" gave way to aggressive campaigns for their clients, industry registration headaches and arbitrarily seized compensation once they left the firm. Rival brokerages where advisors are employees have earned a reputation in the industry as the wealth managers most likely to raid clients,

Many wealth managers have kept the same structure and compensation in place despite a shift in recent years by clients and advisors toward independent firms, which heavily market the benefits of not being tied to a brokerage, said Penny Phillips, the president of

In fact, she said, the industry sometimes feigns its commitment to independence and its corresponding level of client care: the fiduciary duty that places a client's interest ahead of a firm's profits.

"There is always going to be a misalignment between what we're saying and presenting and what we're actually doing," Phillips said. "If you are going to say those things, your contracts, the way you're compensated, the way you think about success has to match that."

The Securian tagline of "independence with a hug" speaks to the

At least five managing partners have left Securian this year, and four others dropped the firm in the previous three years, wiping out roughly one-fifth of its branches, according to FINRA BrokerCheck records. The ex-branch managers said more of them would leave the firm if they weren't indebted for up to hundreds of thousands of dollars in capital expenses or afraid that Securian might put their businesses in limbo by going after their clients or delaying the technical registration change required to join another firm.

"'Independence with a hug' — oh my gosh. It's independence with handcuffs," one former managing partner said. That former branch manager said another branch had been claiming to clients that they had retired from the industry entirely when they left Securian, just for the company to try to grab up some of the departing team's clients. Securian seized tens of thousands of dollars from the compensation of one of the branch's departing advisors, according to the former managing partner.

Another former Securian advisor decried the lack of service and support from the home office — a contrast with what the ex-branch manager called the "countless sleepless nights" the firm caused with its client solicitations and harsh warnings against taking any kind of data to the next company.

"On the way in, all they do is tout that they're an independent broker-dealer," the former managing partner said. "Unfortunately, it's just not true."

A half dozen former Securian managing partners who left the firm within the last five years spoke with FP on condition of anonymity. They asked for their names not to be made public for fear that their former company could sue them, try to poach their clients or otherwise hurt their businesses.

An ex-branch manager contacted FP this summer about Securian's actions and facilitated interviews with other managing partners who recently left the firm. That former managing partner said Securian withheld compensation in order to collect on hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt that the branch manager had amassed. The problem, this person said, is that Securian notified the broker it would be withholding their compensation at 5 p.m. the day before a payday — right in the middle of the former employee's home purchase. At the time, Securian was delaying this person's registration with another firm, leaving them unable to start with the new company, according to the former managing partner.

"If you don't shed light on stuff like this, it'll continue to happen," the ex-branch manager said. "If I go out on a limb and do the greater good for everyone else in my position, I will take some type of a hit."

Lifeblood of the industry

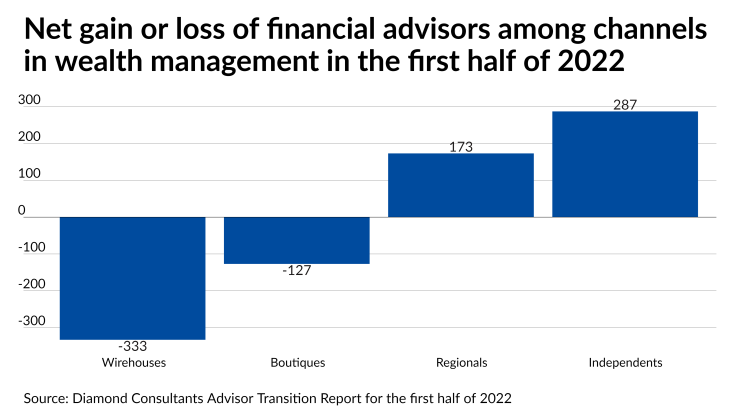

More than

For any kind of wealth manager, those numbers are sobering. At the same time, they underscore the hard-elbowed race for at least a portion of of departing advisors' client assets, according to Doc Kennedy, an

While wirehouse breakaway broker disputes remain the most common source of legal conflicts, Kennedy says that independent firms have their share too. For firms, keeping 10% to 15% of a large exiting team's practice makes their brass knuckle efforts worth it, even if "it backfires on you" one out of 10 times, Kennedy said. He added that while executives are carrying out their duty to shareholders, advisors can spend anywhere from $75,000 to $150,000 pursuing defamation claims.

"The more harm you cause that departing rep's public image and reputation, the more assets will remain at the broker-dealer," Kennedy said.

To industry recruiter Jon Henschen of

"Representatives attending annual conferences notice year to year if advisors are leaving," he said. "Outflow can perpetuate outflow as advisors start to question why the firm is shrinking."

He calls Securian and rivals such as Northwestern Mutual, Equitable Advisors and Principal Securities examples of "captive" wealth managers — ones that push advisors to sell the firm's products to clients.

In the industry's blurry spectrum, these wealth managers go further toward independence than wirehouses and other employee brokerages, which typically retain a larger share of a practice's revenue in exchange for more services such as real estate and payroll. Still, advisors view insurance and asset manager-owned firms as less independent than firms like Commonwealth and LPL, which aren't owned by product manufacturers and have fewer incentives to sell particular products. The conflicts of interest vary by degree among the firms, but even fiduciaries at product manufacturer-owned firms have economic motives to sell the parent company's insurance or investments. Registered investment advisors that have no brokerage affiliation of any kind are seen as the most independent in the industry, although each channel and firm present subtleties that make a lot of the distinctions murky.

In general, independent advisors expect higher pay, greater freedom to serve clients as they see fit and corporate cultures designed to assist independent entrepreneurs.

But that's not available at many captive firms, especially when advisors decide to leave for greener pastures, according to Henschen. Such firms "pull out the big guns" when large practices or branches decide to go to a new brokerage, Henschen said.

"That's the danger of joining captive insurance BDs," Henschen said. "Even though they're putting on the mask of independence, you find the true colors when you try to leave."

Henschen places advisors at firms he views as "real" independent brokerages in the channel that let advisors go without making things difficult for them. But even those firms' recent arbitration records display instances where departing advisors say the firms associated with the greatest degree of independence infringed upon the industry channel's cherished ideals and practices.

Commonwealth has

"That's really the exception more than the rule," he said of intensive fights for clients and litigation against departing advisors. "There are some firms that are more aggressive than others, but by and large it's just not an issue."

While aggressive approaches like defamation or raiding a book of business look bad, many conflicts with departing advisors stem from the language of their contracts, said Brian Hamburger, a lawyer who works with both independent advisors and wealth managers across the industry through

And many firms, independent or not, are simply buying an asset in the form of an advisor's business, Hamburger said.

"They have a reasonable expectation that they will get a return on that asset. Regardless of whether they're independent or captive, I believe that those businesses have a legitimate interest to protect," Hamburger added. "Just because they're independent doesn't mean they should be precluded from using those tactics."

Other independent breakaway sagas

Many of the largest independent brokerages take heavy-handed tactics toward departing advisors and at times have been found to run afoul of FINRA rules or state laws. Arbitrators ordered

Other cases see wealth managers defeating the advisors' claims or at least achieving acceptable outcomes for the firms. Hightower

A FINRA arbitration panel's March decision required Commonwealth to pay Womack compensatory and punitive damages for "willful or wanton conduct" in its "defamatory" Form U5 filing. FINRA members like Commonwealth must file Form U5 amendments explaining the nature of any advisor's departure within 30 days of their exit from the firm. Womack's 18-month quest led to the removal of Commonwealth's language from his permanent FINRA BrokerCheck

In the U5 statement — now scrubbed from BrokerCheck — the company had alleged misrepresentations and a failure to follow its policies. Womack, who's now affiliated with Cambridge through the Asheville, North Carolina-based office of

The firm's U5 amendment cost Womack a client with $5 million in assets and "quite a few" others who "didn't know what to make of the situation," he said.

"To make it worse, I found out during the arbitration process that there were emails from my ex-partner, written after I left the firm, to Commonwealth's compliance [team] asking them to mark up my BrokerCheck quickly so that my personal clients, which I had been in the process of selling to him, wouldn't leave him and consequently, Commonwealth," Womack said. "When compliance finally marked up my BrokerCheck via my U5, emails were produced showing that my ex-partner was sending my clients a link directly to BrokerCheck so they could view the defamatory information presented there in an attempt to retain them for himself."

The former partner, McKelvy of Asheville-based

"We believe we followed FINRA's rules in filling out Mr. Womack's U5 and disagree with the arbitration panel's decision," Commonwealth General Counsel Peggy Ho said in a statement.

Hightower's

The Hightower case took many in the industry by

In Hightower's December 2021 lawsuit, the firm accused Policar of breach of contract, misappropriation of trade secrets, interference with business and unjust enrichment on the grounds that he used its "confidential and proprietary property" for his practice. The lawsuit includes the names of more than two dozen clients identified in the public filing while simultaneously alleging that Policar used its customer lists to compete against the firm in violation of his contract.

The company "expended substantial efforts, through client development services, to identify and cultivate its client base," the lawsuit stated. "It would be difficult, if not impossible, for Policar to start an unknown RIA firm and have 30 clients so far without client information obtained during his 3-year employment with Hightower."

The parties resolved the case in a previously unreported settlement stemming from a mediation session in March, according to subsequent filings. It's unclear whether either side received money as part of the settlement, which placed a one-year ban on Policar approaching Hightower clients and affirmed that he had returned or destroyed any company property. It also codified Policar's right to work with existing clients of his practice and speak or work with family members or friends whose relationships date to March 2021 or earlier.

Representatives for the firm sent a lengthy statement about the requirements of its M&A deal contracts. Just as in Hightower CEO Bob Oros'

"At Hightower, we support fiduciary advisors who want to grow their businesses while simultaneously offering independent financial advice to their clients," spokeswoman Dana Taormina Cleary said in a statement. "Firms that join Hightower agree to long-term relationships with Hightower, and those principals give us appropriate restrictive covenants in exchange for being rewarded for the business they built. Clients become Hightower clients, and we partner with those principals to continue to grow our business together. For those advisors who leave Hightower under this model and don't live up to their contractual commitments, such as taking our confidential information or soliciting our clients, we take appropriate legal action to enforce these reasonable expectations."

In an email, Policar said that the parties reached an agreement, and he was unable to comment further.

What ex-Securian managing partners say

Few wealth management executives are willing to discuss their strategies for dealing with departing advisors. Securian is the

Securian declined to make either the head of its wealth management unit, Executive Vice President of Individual Solutions George Connolly, or its top recruitment and retention executive, Vice President of Individual Career Distribution Tony Martins, available for an interview. The firm declined repeated requests to comment for this story.

Representatives for the Financial Services Institute, a trade and advocacy group for independent wealth managers and advisors that counts Securian and nearly every firm mentioned in this story as

Securian's former managing partners dismiss the notion that the firm is independent. They described an array of steps they said Securian has taken against them and others in an effort to make it tough to relocate to another firm with the same roster of clients. In one move, they said, the company pits the remaining branches against the departing ones.

"You are not allowed to take any client data whatsoever," a former managing partner said. "They actually have reassigned the clients to other active Securian firms in the same states to call your clients."

Pouncing on

"They gave all of our client information to another Securian firm," another managing partner said. "They can call anyone they want, that is no big deal. I just needed them to stop telling lies."

Others say the company halts their compensation, to the tune of tens of thousands of dollars that should have been paid to the departing managing partners or their teams. One said the firm seized the last quarter of earnings out of an advisor's payout, even though the branch had been gone from Securian for two months. Another claimed the firm intentionally held up a paycheck that threatened the advisor's purchase of a family home.

The firm cited the advisor's substantial debt as the reason for keeping the money, the former managing partner said. Its capital financing program is supposed to help managing partners build up a branch's staffing and recruiting. Instead, with declining levels of service from a dwindling home office staff and outdated technology, the financing mechanism often serves as a means of keeping the advisor from leaving for another firm, the former advisors said.

One ex-Securian managing partner said the firm attempted to compel a branch to return the laptops and other hardware they had purchased through the financing, even though the branch was paying the debt. A tech consultant pronounced much of the equipment Securian had required the branch to purchase worthless, anyways.

"They opened the closet and they almost fell on the ground laughing," the former managing partner said. "Nobody uses these things anymore. I didn't get a single bit of utility out of having a server and a backup server in a closet. They made us buy them."

One advisor said that many of the firm's branches are stuck and "leveraged to the point where they can't leave" Securian. Another said they had heard the same thing from many current branch managers.

"To a person they said, 'we would leave, except for the mountain of debt,'" the former managing partner said. "You can't leave because you're going to owe a gigantic check."

U5 filings came up in the interviews with the former managing partners more than any other issues. Several of the branch managers said the uncertainty about when exactly the firm would make their exits official effectively snarled their moves.

"They purposely make it as difficult as possible and slow down the process so you don't move clients over, but also as a warning to other people so they don't consider leaving," one of the ex-managing partners said.

The upshot

For advisors, the stories come as cautionary tales about retaining legal representation and reading the fine print. Many wealth managers are making a bet that advisors won't try to fight back, even though a lot of brokers have "legitimate counterclaims" they could make in an arbitration or another legal case, according to Kennedy, the AdvisorLaw attorney.

"They're all very well accustomed to responding as expected to fear and intimidation," Kennedy said. "The vast majority of the quote un quote victims here are not going to do a darn thing."

In some cases, lawyers can protect departing advisors and ensure they know and understand the terms of any agreement with their new firms, said Hamburger of MarketCounsel. That holds true regardless of whether firms bandy about terms like "independence" and "freedom" to prospective advisors eager to exit from wirehouses, Hamburger said.

"Advisors only move to firms a handful of times throughout their lives," he said. "They can use all sorts of terminology that's appealing to today's financial advisor. But, at the end of the day, the rights and responsibilities of both the firms and the advisors are going to be spelled out in the documents."

With the movement of advisors and assets toward RIAs and greater degrees of independence, the onus is on some firms to change their ways, according to Phillips of Journey Strategic Wealth. Advisors and clients don't bear a responsibility to "suck it up and stay," she said. The firms that don't drop the old scare tactics against breakaway teams will lose many more of them in the end, Phillips said.

"It is further proof that we continue to not always put our money where our mouth is as an industry," she added. "If an advisor feels that the place that they're at is no longer serving them well or serving their clients well, how can we prevent them as an industry from leaving if they're a fiduciary?"