About 42% of people who turn 65 this year will need nursing home care before they die and that care will not be cheap, says Robert Fleming, a principal at Fleming and Curti in Tucson, Ariz., and a speaker at the 2016 NAPFA conference in Phoenix.

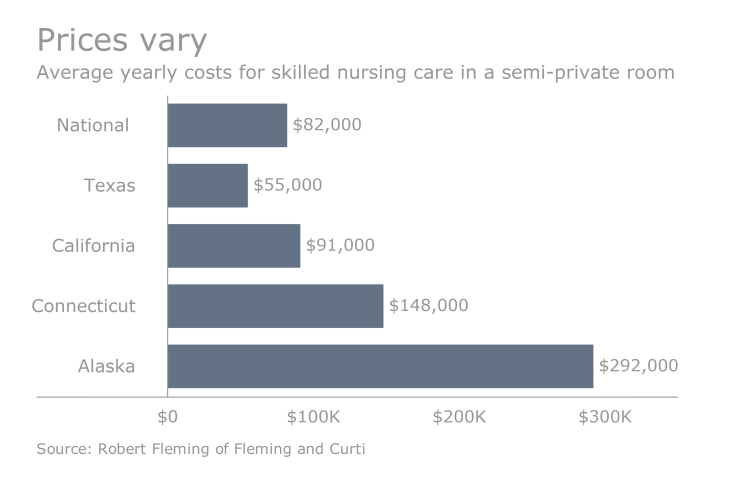

The average price for a year of skilled nursing care in a semi-private U.S. nursing home room is just over $82,000 this year, though costs vary by region. Care in Texas, the least expensive area, runs around $55,000 a year. The annual cost in California is about $91,000; the same bed costs $148,000 a year in Connecticut and $292,000 in Alaska.

A private room costs about 10% more than those average rates. Assisted living costs about half that of a nursing home. Another option, private shift care in a patient’s home, costs about a third of a year in a nursing home, depending on how much care the patient gets. “Nursing home duplication costs between $10,000 and $15,000 a month. It isn’t cheaper to stay home if you need full-time care,” Fleming says.

About half of patients stay in nursing home for six months or so, either dying quickly or recovering from surgery and going home. The other half stays from three to four years until they die.

Between 75 and 80% of nursing home patients are women, Fleming says. “They care for husbands and wear themselves out, and then there’s no one to take care of them.”

Those women, with other family members, provide “a huge amount of unpaid care. In monetary terms, they probably absorb two-thirds of the cost of long-term care,” he says.

With family members, mainly women, taking responsibility for two-thirds of long-term care, who pays for the final third? For long-term patients as a group, Medicaid covers about half of that sum. Individuals pay about a quarter of the bill with their own funds. Medicare pays about an eighth, usually for rehabilitation after surgery or another medical event. Private long-term care insurance pays for just a twentieth of the tab.

Why so little? “The entire long-term care market is flat or sinking,” Fleming says. “Long-term care insurance providers are leaving the market, and costs and premiums are rising. Most of the major plans doubled their premiums a couple of years ago, and that slammed a lot of people who were doing careful planning. Many people reduced their benefits to keep their premiums about the same.”

Some of the other options aren’t so popular, either. “Every state has a partnership plan, and none of them are selling,” Fleming says. But the coverage they offer is improving, he says, giving partnership plans a lot of potential.

“There are some long-term care life insurance hybrid plans, and that’s kind of where the market is moving,” Fleming says. Such plans require a single premium payment and let the policyholder use benefits either for life insurance or long-term care coverage.

“Use it for long-term care and you use up the life insurance benefit, but at least you get it back one way or the other,” he says. “If I had $500,000 lying around to provide for my care, I think that’s what I would buy. But I don’t have $500,000 lying around, and I don’t know many people who do. If you have that much money, you might consider self-funding.” With $1.5 million in assets, plus a house, Fleming says self-insuring becomes a reasonable option, provided the client is willing to risk leaving heirs very little.

Where does Medicaid fit in? Medicaid already covers half of America’s total nursing home bill. Some of its rules vary by state, Fleming says, but “basically, you need to be poor to qualify for Medicaid,” he says. A client could keep $2,000 in resources, plus a home, a car, and a few other items, and can have no more than $2,199 in monthly income. A spouse who doesn’t need nursing home care might keep assets worth between $20,000 and $150,000, depending on the state and how it implements the rules.

Spending down excess resources, gifts, purchasing exempt assets, and purchasing a single-premium annuity are all ways to hasten Medicaid eligibility, as is transferring assets to a irrevocable trust from which the grantor can receive income, but no principal.

Another option is a hybrid solution: Self pay at the beginning and then switch Medicaid. “If you’re in a facility already and you go on Medicaid, you can often stay there,” Fleming says. “Plus the idea that facilities that accept Medicaid aren’t very nice just isn’t true. Every nursing home is full of Medicaid recipients. A handful of facilities won’t accept Medicaid, but they often don’t offer the best care, because they don’t have a high enough population to maintain a skilled nursing program.”