Editor's note: To help advisors coordinate year-end planning for Roth conversions and mutual fund capital gains, we have republished this story, which originally ran Aug. 15.

Can a Roth conversion affect the taxation of long-term capital gains?

Significantly.

That’s because Roth conversion income, like all other ordinary income, reduces the benefit of the LTCG rates, increasing the overall tax cost of the conversion. This interplay can easily throw off even the best tax projections, especially when they rely on the low (or even 0%) LTCG rates stated in the Tax Code. When there is additional ordinary income, like Roth conversion income, those favorable tax brackets are not as attractive as they appear to be.

Since Roth conversions cannot be undone anymore — the tax law changes eliminated recharacterization of Roth IRA conversions beginning in 2018 — advisors should be careful to do an accurate projection of the tax effect of a Roth conversion. The tax will have to be paid. But the permanency of a Roth conversion does not mean it should be avoided. Roth IRAs still offer long-term tax benefits — mainly tax-free growth and no lifetime required minimum distributions for Roth IRA owners, allowing more tax-free accumulation and a hedge against future tax increases.

In fact, if IRA funds are not converted, eventually those IRA funds will be subject to RMDs and those RMDs will similarly cause an increase in capital gains taxes — and at possibly higher future tax rates. That’s why Roth conversions should still be seriously considered while today’s tax rates are at historic lows. However, the tax cost of the conversion needs to be more accurately projected since the tax due cannot be reversed.

Planners and tax advisors should evaluate additional so-called stealth taxes triggered when income is increased by a Roth conversion. Stealth taxes are other indirect tax increases that occur when income is increased. If not addressed, the client may see a higher tax bill than was planned. That won't go over well at tax time next year.

Capital gains should be added to the list of stealth taxes to be considered when projecting the true overall tax cost of a Roth conversion.

Some of these stealth-type tax increases result from the increase in adjusted gross income from a Roth IRA conversion. AGI is a key amount on the tax return and an increase can cause the loss of valuable tax deductions, credits and other benefits.

Some of these well-known items include medical deductions; additional taxes on Social Security benefits and Medicare surcharges; education-related tax benefits (and financial aid eligibility); child tax credits; deductible real estate losses; Roth and IRA contribution limitations; as well as the new (as of 2018) 20% deduction for qualified business income, aka “the 199A” deduction available to certain self-employed business owners, to name a few. These stealth increases add to the tax bill for a Roth conversion. But Roth conversions can also substantially increase the tax on long-term capital gains.

These very favorable LTCG rates generally apply to capital assets held for more than one year. The rates have been made more attractive by the tax law change. For example, the rate is 0% for capital gains of up to $78,750 in 2019 for a married couple filing jointly. But a Roth conversion can reduce or even eliminate the benefits of the lower capital gains rates. This is something that is not widely noticed until it is seen on the completed tax return, which, of course, is too late. Capital gains should be added to the list of stealth taxes to be considered when projecting the true overall tax cost of a Roth conversion.

How Roth conversion income affects capital gain income

Roth IRA conversion income is ordinary income and is taxed the same as wages, pensions and other IRA distributions and short-term capital gains.

Our tax system taxes ordinary income first, and then capital gains. This means that ordinary income, like a Roth conversion, reduces the benefits of the lower capital gains rates. In its most simple form, a $100,000 Roth conversion could completely eliminate the 0% capital gain rate bracket pushing more of the capital gains into the higher brackets of up to 20% or 23.8% when Roth conversion income (or other income) pushes AGI up high enough to trigger the 3.8% tax on net investment income.

A married couple filing jointly has no income other than a $100,000 LTCG. In 2019, they will owe zero tax. The LTCG of $100,000 is first reduced by the standard deduction (assuming both spouses are under age 65) of $24,400, resulting in a net LTCG of $75,600, which is under the $78,750 limit for the 0% rate, so no tax will be owed.

Now let’s add a $50,000 Roth conversion. That will increase the tax on the LTCG from zero dollars to $7,028. The tax on the Roth conversion is only $2,684, but the total tax bill will be $9,712.

The $50,000 Roth conversion (or any other additional ordinary income) will get taxed first using the ordinary income tax brackets. The $50,000 Roth conversion (assuming this is the only other income) will be first reduced by the 2019 standard deduction of $24,400, leaving taxable ordinary income of $25,600, and that amount reduces the 0% capital gains bracket available for the $100,000 LTCG.

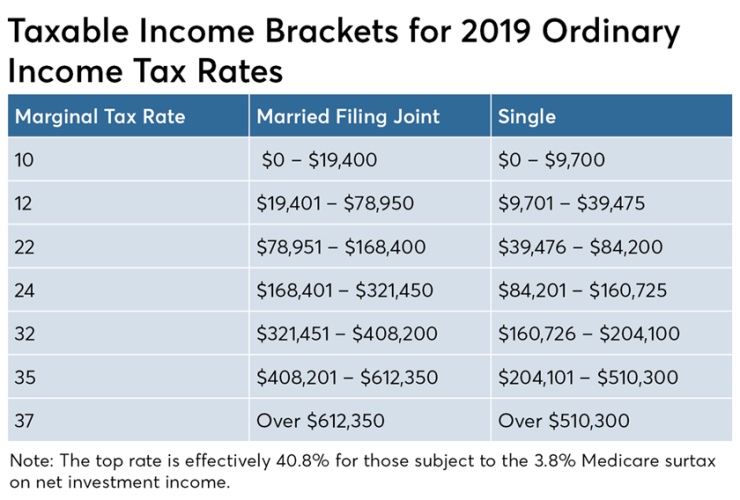

The $25,600 is taxed using the regular tax brackets, so that tax is $2,684. Here's the math if you'd like to follow along :

$19,400 at 10% = $1,940

$6,200 at 12% = $744

$25,600-----------$2,684

The $100,000 LTCG tax now goes from zero to $7,028. That’s a substantial — and often unexpected — increase.

The benefit of the zero to $78,750 LTCG bracket is reduced by $25,600, which was taxed at ordinary income tax rates, so only $53,150 is being taxed at 0% (the $78,750 less the $25,600 = $53,150). The remaining $46,850 of the $100,000 LTCG is now being pushed into the 15% LTCG bracket and the tax on that $46,850 x15% = $7,028.

$53,150 at 0% = $0

$46,850 at 15% = $7,028

$100,000--------- $7,028

Bottom line: In this simple example, the $50,000 Roth conversion was not only subject to its own ordinary income tax of $2,684, but also triggered a $7,028 tax on the LTCG that, without the Roth conversion, would have incurred zero tax. That’s important information for a client, especially with larger amounts at stake than in this simple example.

Now let’s say we change the example by adding a Roth conversion of $120,000 to the client’s LTCG of $100,000. The $120,000 Roth conversion eliminates the entire benefit of the 0% LTCG bracket, triggering a LTCG tax of $15,000 — all at 15%, and none at 0% on a LTCG that, without the Roth conversion, would have incurred zero tax. In addition, there will be a tax of $12,749 on the Roth conversion, for a total tax bill of $27,749.

3.8% tax effect

If the income from the Roth conversion goes even higher, in addition to an increased tax on the LTCG, it could trigger the 3.8% tax on net investment income resulting in a capital gain tax of 18.8% or even 23.8%. In fact, in some cases where there is a large capital gain, the tax rate on the capital gain could exceed the tax rate on the Roth conversion, adding to the tax cost of the conversion.

The Roth conversion income itself is not subject to the 3.8% tax because it is not treated as investment income for this tax calculation. But it can increase MAGI to the point where the 3.8% tax can apply to investment income like the LTCG or interest and dividend income. That, too, must be factored in when higher income clients with capital gains are considering a Roth conversion.

Reverse tax benefit

The tax effect works in reverse as well to the taxpayer’s benefit. While additional income, like Roth conversion income, will increase the LTCG tax, reductions in income, for instance making or increasing a pre-tax 401(k) contribution or deductible business losses, will reduce both the tax on the Roth conversion and on the LTCG.

All these examples are assuming the taxpayer is using the standard deduction which, under the current tax law, many more taxpayers are. If instead, the taxpayer had large enough deductions to itemize, that would obviously lower the tax cost of the Roth conversion, but it would also lessen the tax impact on LTCGs, allowing more of the LTCG to be taxed at lower brackets.

Remember that the Roth conversion once done, cannot be undone.

Remember that the Roth conversion once done, cannot be undone. Tax projections must be accurate and take numerous related stealth taxes into account, including LTCGs.

All of these tax calculations happen automatically on the tax return, but by the time the tax return is prepared the following year and the actual tax impact is seen, it’s too late to make any changes. Tax planning programs can be a big help, since the actual tax return preparation programs won’t be available until early next year, which again would be too late to deliver the news.