Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

The economy’s K-shaped recovery from the pandemic has been good news for America’s private banks. Clients of these high-end wealth managers — investors at the top of the net worth pyramid — generally are faring well during the pandemic, at least financially. That leaves private bankers free to contemplate a more existential problem: how to hang onto the richest families as their brand of rarefied exclusiveness comes under fire from family office providers and registered investment advisors who aren’t part of banks.

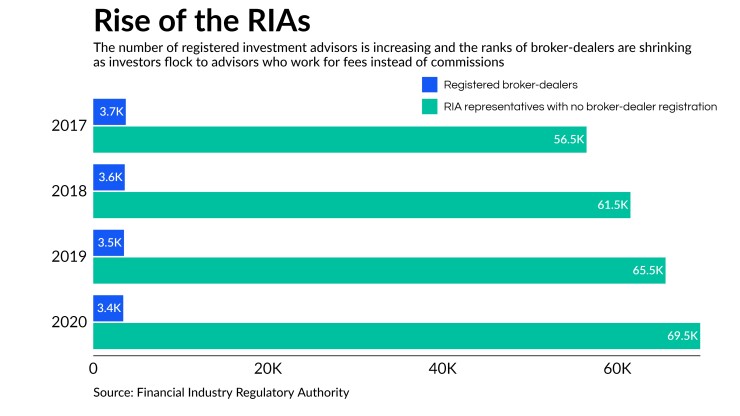

The trend is clear: Right now, the vast majority of brokerage assets, financial advisors and clients are affiliated with brokerages. But over time, investors, their money, and their advisors have been inexorably migrating from commission-based brokerages and toward the fee-only RIA model.

In 2020, just 10% of registered representatives worked at RIAs, FINRA data shows. But in the past 8 years, the number of FINRA-registered broker-dealers fell by 17%, while the tally of RIAs registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission and with state securities regulators went up by 12%. And in the last four years, the number of RIAs who aren’t registered with a broker-dealer — the pure fee-only RIAs, who hew to the fiduciary standard of client service — jumped by 23%.

Leaders of private banks — which include some Most Powerful Women honorees — say they are holding their own in this competition.

“We aren’t viewing ourselves as having to go toe to toe with RIAs,” said Julie Caperton, who took over this summer as head of Wells Fargo Private Bank. Her bank is hedging its bets on client acquisition: Wells has a traditional brokerage and an RIA arm, as well as the private bank, allowing clients to choose which model they prefer for financial advice, Caperton pointed out.

Some executives argue private banks benefit from the perception that it’s more streamlined for clients to deal with just one financial institution than several.

“Twenty to 30 years ago, you might have kept your banking business in one place and investment portfolio in another, or you might have taken your investment portfolio and split it up among a number of places,” said Catherine Keating, the chief executive of BNY Mellon’s Wealth Management and Investor Solutions divisions. “Clients don’t feel the need to divide it up anymore.” It’s less expensive and easier to work with just one financial advisor, or at least to have one as your primary provider, she said.

One main differentiator between a large private bank and a smaller firm, bankers say, is that a private banker acts almost as a concierge, connecting clients with services elsewhere in the bank, like lending, mortgages or merger advice.

“I can’t tell you how many times I get a call for something that should be the commercial bank or consumer bank or investment bank,” said Katy Knox, president of Bank of America’s private bank. “I tell my team, ‘Be so proud that you can be that first call for any strategic question that a client has and be able to navigate the company for them.’ We work really hard at that.”

This ability to mine one division’s clientele for a new source of revenue for another division is why private banks frequently court executives of their institutions’ investment banking clients, or offer a private bank account to every associate at a top law firm, many years before the young attorneys have the asset levels to qualify on their own.

“Most of our clients are doing multiple things with us,” said Ida Liu, global head of Citi Private Bank. “They value the fact that we’re so comprehensive, institutional and global.”

Her boss, Citigroup CEO Jane Fraser, similarly cites the cross-divisional reach as a reason wealth management overall matters to the company.

“We’re pretty excited about the wealth opportunity for us because we have all the different pieces to be successful here: the brand, the client relationships, the platform, the commercial banking franchise,” Fraser told research analysts on a July call to discuss Citi’s second-quarter

earnings. “And we’re already a sizable player.”

But there’s a problem: ask a sampling of high-net-worth investors about why they are private bank clients, and they’ll cite factors such as the bank’s lending capabilities, ability to move quickly and issue loans against a variety of assets, and its global reach. They may also note that a private bank can help get them into elite investment vehicles — private equity, venture capital or hedge funds — that they couldn’t have accessed otherwise, even if they themselves work in finance or have strong networks.

What they aren’t likely to mention is how well the private bank manages their money. To solve this disconnect, private banks are trying to pitch their services for more specialized investment strategies, like offerings focused on environmental, social and governance factors or impact investing.

“Coming through a global pandemic, people are very focused on purpose and values,” Keating said. “It makes you stop and think about what’s important to you.”

Read more:

The Most Powerful Women in Banking The Most Powerful Women in Finance The Most Powerful Women to Watch

Keating noted that, unlike decades past, when executives had defined-benefits plans that their company managed for them, today they typically have 401(k)s and personal savings that they have to manage themselves or pay someone else to invest. Increasingly, she said, clients are interested in ESG investing, especially given “more information that shows it doesn’t necessarily have to dampen returns.”

As wealth management overall moves toward passive, low-fee investments, private banks are also reminding clients that sometimes you need a hand on the tiller — even if it costs more.

“Anytime that there’s a crisis in the markets or a pullback, you’re definitely going to want to be with people who can actively manage,” said Nelle Miller, a managing director and co-head of the New York market at J.P. Morgan Private Bank.

The large private banks are also trying to make their staff ranks look more like their clients’ demographics.

As an industry filled with financial advisors who are overwhelmingly white, male and nearing retirement age, wealth management as a whole has a problem with advisor diversity. Private banks have to face the issue quickly if they’re going to attract young business owners and the grandchildren of the world’s wealthy, who come from a variety of backgrounds and ethnicities and tend to care more about diversity as a value.

They’re doing better than their industry on this measure. “I had a client say to me, ‘I commend you because your team resembles the UN,’ ” said Liu, who notes that her team is “half women and two-thirds diverse.”

“We need to mirror the clients we do business with to serve them well,” Liu said.

As baby boomers transfer their $30 trillion of wealth to their children over the next two decades, younger investors — half of whom are women — will inherit their accounts.

“We want to mirror the clients we’re going to be working with,” said Keating, noting that 60% of her leadership team is diverse and 40% of vice presidents and above are women, as are 50% of her unit’s employees.

The objective of recruiting a wide variety of bankers is to facilitate personal relationships with clients, the executives say.

“Clients don’t call and say, ‘I really love your tech or your investment in XYZ,’ ” Miller said. “Sure, they care about that, but they really care about the person who’s helping them with whatever’s on their mind, how they work with their family members, how they listen and react.”

Citi’s approach to client families is to have the most senior (and oldest) bankers work with the patriarch’s generation, while younger associates work with their children and the most junior bankers assist the grandchildren. Pairing the ages this way allows for better connections between the clients and their own bankers, and it “enables our junior bankers to develop faster,” Liu said.

“We’ve been really adopting the family approach to make sure we’re not just working with a single relationship head but also with the spouse, kids, grandkids and building a longstanding relationship over the generations to come,” she said.

Read more:

In this sense, the pandemic has been a gift: As older clients embraced Zoom, it became easier to schedule multigenerational check-ins with the family’s financial advisor. While grandkids may not have always been eager to fly in for such meetings, most had no problem connecting via iPad to meet with their parents, grandparents and private bank team.

“I always tell the team, ‘Don’t underestimate the voices of even the youngest people in the family,’ ” Knox said.

It’s a matter of relatability. When Caperton’s son was starting his first semester of college this fall, she had him contact the family’s private bankers to line up his accounts and a credit card to take with him.

“He was so much more comfortable calling the younger members of the team than my advisor,” she said.

As part of their drive to become more modern, private banking units can be found hurtling into areas that more traditional parts of the bank can’t.

Take cryptocurrency. Investors are clamoring for access, but it’s not an asset many bankers are likely to recommend for the average or even the affluent investor.

“Clients call every day on crypto,” Miller said.

The groundswell of interest is “a huge FOMO [fear of missing out] thing. Everybody went to the best party and everybody’s talking about it and now everybody wants to be involved.” Like many of its rivals, J.P. Morgan this summer launched access to crypto funds for clients.

Catering to the wealthiest clients means wading into areas of finance where the regulations largely haven’t been written and the risks are unknown.

“We’re committed to be a trusted partner as these new products and services develop,” Keating said.