Engage in uncomfortable reflections and conversations.

Make mistakes so you can learn from them.

And, above all, treat team members, clients or prospects with respect.

These are three of the many ways that financial advisors can act as allies or even accomplices or co-conspirators in the fight to close the racial wealth gap and promote workplace equity for women, Black Americans, Latinos and other minorities, according to panels at this week’s CFP Board Center for Financial Planning Diversity Summit. For starters, calling yourself an “ally” doesn’t make it so, said Elissa Sangster, the CEO of the Forté Foundation, a nonprofit consortium of companies and college programs advancing women in business careers.

The Austin-based Sangster and Whitney Tome, a principal with Washington, D.C.-based public affairs and communications firm The Raben Group, gave presentations on allyship, while Wes Thompson, the CEO of Portland, Oregon-based planning and insurance firm M Financial Group and Lori Anne Douglass, founding partner with New York-based estate and succession law firm Douglass Rademacher, spoke as part of a session on the wealth gap.

“You have to be given that label by another, so it's not yours to claim,” Sangster said of being an ally. “There are no right answers or right behaviors. There is a path and you can think about allyship really as a continual journey. It's about developing a lens of awareness and adapting in any given situation.”

Sangster credited David Smith and Brad Johnson, authors of “

“It is not the ‘giving up’ per se of it, it is leveraging it so that others have the same access, the same privilege, the same chances for those key roles because, often, history has shown us that certain people don't get that access,” Tome said. “Essentially, they raise all boats. It's also the recognition that a lack of privilege on one side actually hurts everybody, so this isn't a one-sided conversation.”

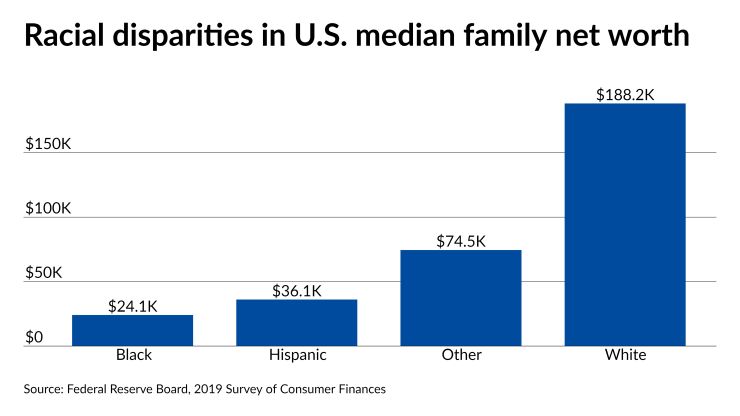

She recommended that advisors and other wealth management professionals think about it as baking more pies for Thanksgiving rather than giving up pieces out of the same one. Still, with data

“As we build wealth, it also drives the need for professional advice,” Thompson said. “Iterative and effective financial advice is really critical and is a critical component of advancing economic empowerment for people of color.”

That makes hiring more women and minority professionals in the industry especially important, he added. In that regard, running practices and workplaces that give advisors, employees, clients and prospects from historically excluded groups equal treatment makes a difference as well, said Douglass.

Meeting advisors with cultural understanding “makes it a little easier” on clients who may not be used to talking about their finances, Douglass said. “I've had clients that have really been insulted by their advisors because they haven't saved enough or planned enough, or they don't invest properly. And so by the time they are going, they're like, ‘Oh, this is all you have?’”

Advisors may never see a prospect or staff member again after speaking to them in that manner, but the panelists said they should be prepared to go on a personal journey. The process of becoming an ally entails some errors along the way, according to Sangster.

“It's important to remember that mistake-making is part of the allyship process,” Sangster said. “It's actually imperative in it. The glasses prescription you start with won't be the one you have later on in your journey, and we hope your interest in gender equity leads you to a broader pursuit of other equity issues as well. There are so many things that you can uncover and learn more about.”

Tome defines “allyship” as “the unlearning and relearning to operate in solidarity with the group,” which demands a personal analysis about what you’re reading or how you’re educating yourself about marginalized groups. An “accomplice” begins to challenge the status quo, as in the case of white people who participated in protests of segregation alongside Black activists, she said. The next stage is being a “co-conspirator.”

“This is when you're really putting yourself on the line as much as the people who you are supporting,” Tome said. “And this really goes a step further, right? To say, ‘I don't just say it. I don't just talk about it, but I actually do it in action.’ And that requires that you actually leverage your power and privilege for others.”