The U.S. economy has been in a low-inflation environment for the past decade. But in a twist on the old cliché: When it comes to inflation, what goes down, must come up.

The average annualized rate of inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index has been 1.61% since 2008, as compared to 3.99% since 1970. If cycles repeat, and they do, inflation will indeed tick back up again. When it does, commodities will be the likely winner, as demonstrated in the chart “Low and High Inflation.”

Over the past 48 years (1970-2017), commodities had an average annual gross loss of 1.97% (-4.03% average real return) during the 24 years with below median inflation. In comparison, in the 24 years with above median inflation, commodities had an average annual gross return of 21.98% and an average annual real return of 15.13%.

The performance of commodities here is based on the S&P Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (GCSI), the only commodities index with a performance history going back to 1970.

The 48-year historical performance of large-cap U.S. equities in the chart is represented by the S&P 500, while the performance of small-cap U.S. equities was captured by using the Ibbotson Small Companies Index from 1970 to 1978 and the Russell 2000 from 1979 to 2017.

The performance of non-U.S. equities was represented by the Morgan Stanley Capital International EAFE Index (Europe, Australasia, Far East) Index. U.S. bonds were represented by the Ibbotson Intermediate Term Bond Index from 1970 to 1975, and the Barclays Capital Aggregate Bond Index from 1976 to 2017. Cash was represented by 3-month Treasury Bills.

The performance of real estate was measured by using the annual returns of the NAREIT Index (National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts) from 1970 to 1977. From 1978 to 2017, the annual returns of the Dow Jones U.S. Select REIT Index were used.

If a client owns a commodities fund as part of a broadly diversified portfolio, they must be able to roll with the leaner times.

Over the past nine years from 2009-2017, commodities produced an annualized gross return of -4.84% (based on the S&P Goldman Sachs Commodity Index).

That’s a pretty rough go. But over the past 48 years, the GSCI produced an annualized gross return of 6.99% (2.88% real return). It can certainly be feast or famine with commodities. But when inflation heats up, commodities benefit because rising commodity prices are often the very cause of inflation.

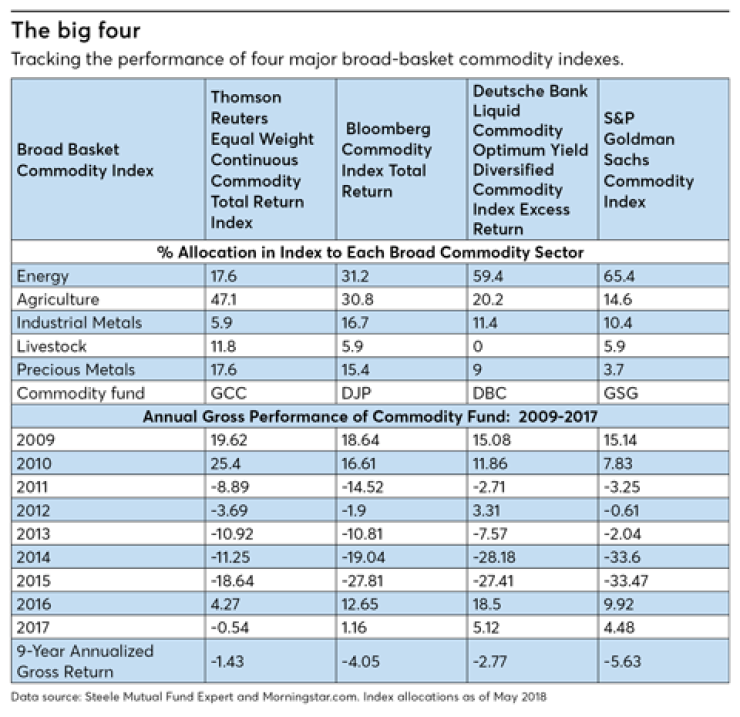

While the GSCI is an important commodity index, there are other broad-basket commodity indexes worthy of consideration, which can be seen in the “Big Four” chart. I am focusing on these particular indexes because of their prominence and the differences in their methodologies. The choice of index matters because the composition often illustrates the allocation model that commodity mutual funds and exchange-traded products mimic.

For example, the Thomson Reuters Equal Weight Continuous Commodity Total Return Index has a much lower allocation to energy than the Deutsche Bank Liquid Commodity Optimum Yield Diversified Commodity Index Excess Return (17.6% vs 59.4%).

The S&P Goldman Sachs Commodity Index has an even higher allocation to energy, at 65.4% (as of May 2018). Thus, the funds that track each of the different indexes will have markedly different allocations to energy.

The four commodity funds we are considering here are the WisdomTree Continuous Commodity Index Fund (GCC), the iPath Bloomberg Commodity Index Total Return (DJP), the Invesco DB Commodity Index Tracking Fund (DBC) and the iShares S&P GSCI Commodity-Indexed Trust (GSG). DJP is an exchange-traded note; the other three are ETFs.

You will note that, in 2014 and 2015, DBC and GSG both had large losses due to their higher allocation to energy — an allocation specified by the indexes each fund tracks.

By contrast, GCC and DJP had relatively better performance based on their smaller allocations to energy. Suffice it to say, 2014 and 2015 were very rough years for oil. The largest commodities fund dedicated to the energy sector is United States Oil Fund (USO). In 2014, USO had a gross return of -42.36%, followed by a loss of -45.97% in 2015. When oil prices rebound, however, DBC and GSG may perform better than other broad-basket commodities funds with a smaller allocation to energy.

Consider also the different allocations to agriculture. GCC has a 47.1% allocation, whereas GSG has a 14.6% allocation. Big difference. The allocation to precious metals also differs widely, with GCC and DJP both over 15%, while GSG is below 4%.

The point is that the allocations to the various commodity sectors differ substantially among the various commodity indexes (and the funds that track them), and this affects the performance from year to year. For example, in 2010 GCC had a return of 25.40%, whereas GSG had a return of 7.83%. In 2016 DBC was up 18.5%, whereas GCC only posted a gain of 4.27%. (All these returns are gross.)

Of course, very few investors have a portfolio that contains only a commodities fund. Thus, the more relevant issue is how well a commodities fund contributes to the overall performance of a client’s portfolio.

We can test this by inserting each of these four commodities funds into a broadly diversified portfolio and measuring the overall performance over the past nine years. This time period was chosen because that is the longest common performance period for all four of the funds (GCC’s first full year of performance was 2009).

Over the past nine years, if GCC was used as the commodities fund in a 12-asset-class portfolio (with an 8.33% allocation each to large-cap U.S. stock, midcap U.S. stock, small-cap U.S. stock, non-U.S. stock, emerging stock, real estate, natural resources, commodities, U.S. bonds, U.S. TIPS, non-U.S. bonds and cash), the average annualized gross return was 8.59%.

This was assuming annual rebalancing at the end of each year. If DJP was used as the commodities fund, the nine-year annualized gross return was 8.38%. If GSG was used, the gross return was 8.29%. And if DBC was used, the nine-year gross return was 8.52%.

Clearly, which commodities fund you advise a client to invest in matters on a year-to-year basis if their only portfolio holding is a commodities fund. But in a broadly diversified portfolio, it matters less which commodities fund you select, as shown by the similarity in the overall portfolio.

This should be comforting because it removes the pressure to pick the right commodities fund. The key is to have exposure to a broad-basket commodities fund that will provide upside performance potential when we experience our next round of inflation. And we will.

This story appears in Financial Planning’s