For clients who need long-term attention, the home-sweet-home solution unfortunately may be a money pit.

A

Preferences may not lead to practicality, though. “It's hard to ‘age in place,’ for seniors who live alone, especially if family doesn't live close by or in the case of advancing dementia,” says Jennifer Cray, partner at Investor’s Capital Management in Menlo Park, California. “It's less expensive in the beginning when the care needs are still light. But over time, it can get more expensive than living full time at a facility.”

For advisors, the challenge is to make home care more affordable.

How expensive can it be to bring in caregivers? The Genworth 2017 Cost of Care Survey puts the national median cost for homemakers’ services at around $4,000 a month, or $48,000 a year, with a similar median for home health aides. Those costs assume the care totals 44 hours a week, or about six hours a day. More hours would boost the bills, as would living in a high-priced area. In some surprising places like Iowa and Kentucky, the annual costs for even a 44-hour week can top $100,000 a year.

MORE, NOT MERRIER

People preferring to stay in familiar surroundings may be clients or their parents, and may be either single or married. “Usually, one spouse — often the husband — needs care, which is provided by the other spouse,” says Judy Ludwig, vice president of financial planning services at Braver Wealth Management in Newton, Massachusetts. “Some outside support will help to care for the ill individual who would prefer to stay at home.”

Advisors with clients opting to stay in more expensive states need to be prepared to help them with those costs.

Traditional marital roles may also be reversed. Debbie Gallant of Gallant Financial Planning in Rockville, Maryland, tells of clients in which the wife was 75 years old and the husband was 85. They needed to downsize out of their five-bedroom, three-level house, so they moved into a two-bedroom apartment, instead.

Then disaster struck.

The wife was in a head-on collision, then spent 10 weeks in an ICU and in rehab before she was discharged to the care of her husband.

“Due to her injuries, they were able to activate her long-term care policy from day one, as it covered home care,” says Gallant. The policy, purchased 14 years earlier with a 5% inflation adjustment and no elimination period for home care, had grown to pay $350 a day. Those benefits, along with the proceeds of the home sale, her IRA, her teacher’s pension and Social Security covered their costs. Altogether, they were paying $3,700 per week for care plus their normal living expenses at their apartment.

According to Gallant, the extra outlays for staying in their apartment included 24-hour caregivers, a geriatric social worker who visited twice a month and someone to organize their medications each week. The couple also needed to modify their new apartment by installing grab bars in the bathroom and widening doorways, and they bought a walker, a portable wheelchair, a hospital bed, a seat for the shower, a portable toilet and medical alert necklaces.

In many cases, notes Ludwig, food expenses also usually increase as caregivers also need to be fed. And Carmen Wong, partner and senior wealth advisor at Confluence Wealth Management in Portland, Oregon, reminds clients not to overlook transportation costs, especially if the most desired medical specialists are not located within close driving distances.

Eventually, Gallant says, both spouses mentioned above saw their health decline so much that they had to move into an assisted living home. Ironically, even at $8,000 to $10,000 a month, the facility was less expensive than hiring caregivers to come to the apartment.

HIGHER CEILINGS

Therein lies the dilemma. Clients probably will prefer to stay home if they need long-term care, but the costs can be overwhelming. How can advisors approach this topic?

-

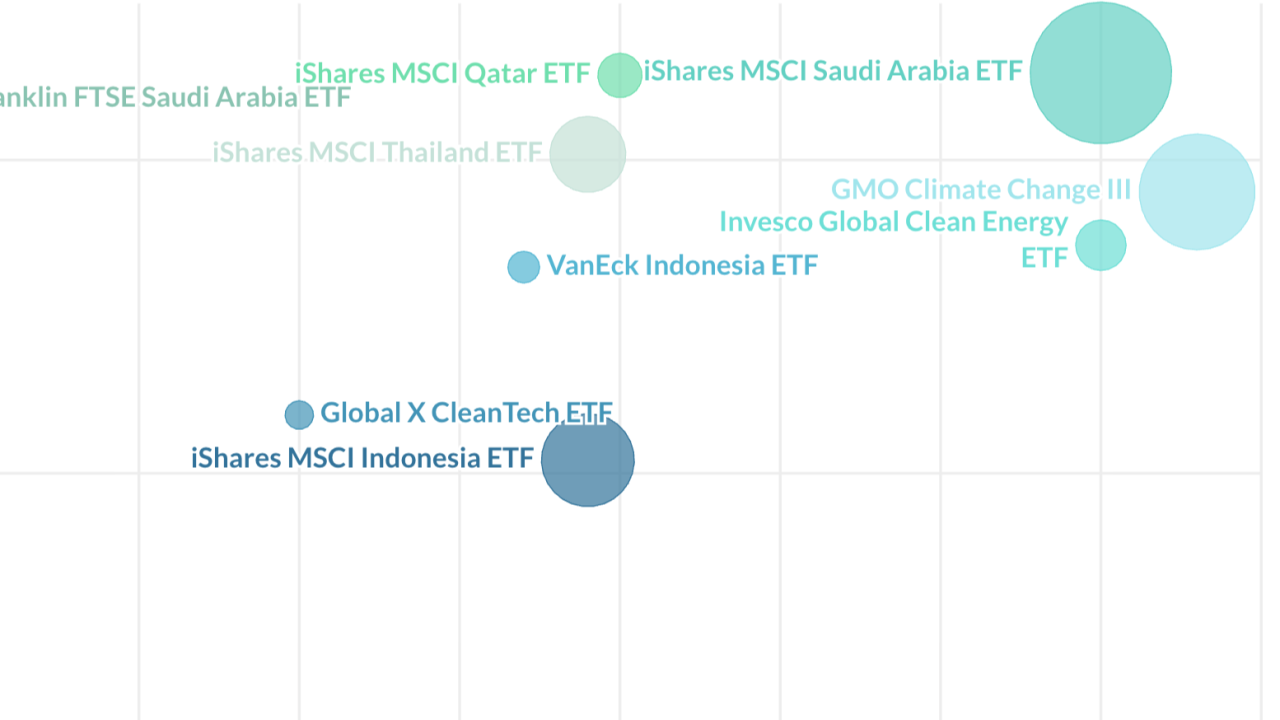

The cost of home care is up over 6% this year nationwide. Are your clients living in an even more expensive state?

October 30 -

Where your client resides may determine how much they'll need to pay.

November 14 -

Advisors with clients opting to stay in more expensive states need to be prepared to help them with those costs.

October 19

Step one entails recognizing the costs of home care and adjusting financial plans accordingly. “I’ve been surprised at how expensive long-term care can be,” says Cray. Sources such as the Genworth Cost of Care survey cite median costs by area, but that’s just the median. In reality, costs can be vastly higher, even for the basics, she says.

Cray reports that her firm is changing its modeling for the potential costs of long-term care. “We’ll probably add about 20% to the already high numbers we’ve been using,” she says. “Finding that extra money won’t be easy. We may suggest saving more and holding more cash. When someone needs care and is living in a house they’ll need to keep in good repair, the cash needs can be enormous.”

Planning also can include buying LTC insurance with home care coverage. “I tell my clients that the 14 years of premiums that this couple paid for their LTC insurance were recovered in about six months of benefits,” Gallant says.

“Clients probably will prefer to stay home if they need long-term care, but the costs can be overwhelming.”

Tax savings can help too, at least under current law. For the couple described above, the long-term care reimbursements from their LTC insurance policy were not taxable. In addition, unreimbursed long-term care costs were deductible above 7.5% of their adjusted gross income. (Proposed tax legislation would eliminate this deduction, which now kicks in above 10% of AGI.)

“Long-term care insurance is something we might use, but costs are high,” says Cray. “We’ll be looking at annuities with LTC riders as an alternative. Conceptually, I like the idea of a pool of money that can be used for different purposes. However, with insurance products it’s vital to look closely at the details.”

Wong adds that life insurance cash value also can be used to help cover LTC costs. “Another case we are working on involves clients who have not purchased long-term care insurance,” she says. “We are exploring strategies to allocate a part of the retirement account to a designated pool of assets earmarked for long-term care, which may eventually morph into an annuitized income stream to fund part of the monthly needs.”

MONEY FROM HOME

LTC insurance can help cover home care costs, along with other income sources and drawing down savings. “Sometimes the children pitch in to help financially,” says Ludwig.

Still, there may be a gap — one that might be partially filled with home equity. “In many parts of California, for example, home equity is by far the largest asset that many people have,” Cray says. A reverse mortgage might provide a lifelong source of untaxed cash flow, but come up short.

Where your client resides may determine how much they'll need to pay.

“The amount of equity that can be made liquid with a reverse mortgage is limited and would only cover a few years of high-cost care,” says Cray. “It's not a solution for everyone who wants to stay in their home.” For the couple mentioned above, Gallant recalls, “A reverse mortgage could not possibly have provided the income stream that they needed to pay for their care once they required more than just a few hours a day.”

Online, advisors can find many reverse mortgage calculators to give clients an idea of what they can expect. At reversemortgage.org, for instance, the calculator indicates that a free-and-clear house in Peoria, Illinois valued at $500,000, could qualify for a federal Home Equity Conversion Mortgage (HECM) with cash advances around $1,250 a month to a couple, both age 72. In 2017, the HECM limit is $636,150 of home value, putting a cap on loans backed by more expensive properties.

Ludwig asserts that reverse mortgages can work but they are tricky, and they come with fees. “I strongly recommend that a professional review any documents that the couple has to sign before they turn over their house to a lender,” she says.

ON THE SELL SIDE

Selling the house could free up even more home equity, but how can such a sale be reconciled with a desire to stay home for LTC? One tactic is to sell and move into a smaller and presumably less expensive place, as Gallant’s clients did. For individuals, up to $250,000 of gain from the sale can be tax-exempt, and for married couples filing joint tax returns, the cutoff increases to $500,000. Recently widowed clients may also qualify for the larger exemption, provided they sell their home within two years of their spouse’s death.

Another tactic, mentioned by Ludwig, is for the children to purchase the home from a parent or parents needing care, which can provide needed cash. The parents can then rent the home from the children or the children can gift the value of the rent to the parents, she says. The annual gift tax exclusion — the limit for gifts without tax consequences — will be $15,000 per recipient in 2018, up from $14,000 in 2017.

Tax-wise, it would be better to keep the home and get the basis step-up, Cray says, so at the owner’s death, the heirs could avoid income tax on a subsequent sale. If money is needed immediately, a sale might be necessary, but the $250,000 or $500,000 capital gains exclusion may not cover the full gain on some homes.

As Cray observes, “that's a fortunate problem to have.”

Not all problems arising from long-term home care are so fortunate. Advisers can become part of the solution by apprising clients of the possible costs involved, and starting early with a financial plan designed to help clients stay put as long as possible.