Perhaps you have some clients who have kept a high percentage of their portfolio in cash for several years, or newer clients who have been hesitant to fully deploy the equity portion of their portfolio. They fear another steep decline, similar to the one we saw in 2008 — specifically in global equity markets, but most notably in the U.S. equity market.

These fears are understandable. As shown in the chart “Past decade for U.S. equity,” large-cap U.S. stocks have produced nothing but positive annual returns since 2009. For a broader perspective, since 1970, the batting average of large-cap U.S. stock has been 81%. Over the past 10 years, the S&P 500 has produced positive returns 90% of the time.

So we’re in a positive streak that is above the 48-year average.

Small-cap stock U.S. stocks have produced positive annual returns 71% of the time going back to 1970. Over the past 10 years, small-cap U.S. stocks (as measured by the S&P Smallcap 600 Index) have produced positive annual returns 80% of the time — also higher than the historical norm.

Midcap U.S. stocks do not have a performance history going back to 1970, but since 1992 they have produced positive annual returns 77% of the time. Over the past 10 years, midcap stocks have generated positive annual returns 70% of the time — so a bit under its longer-term average. However, two of those negative returns (1.73% in 2011 and 2.18% in 2015) were relatively trivial.

Clients may be afraid to start investing now because they think the stock market will tank sooner rather than later, and they want to avoid that bad-timing experience. But a client cannot stay on the sidelines hunkered down in cash forever, unless that person has a ton of money and is well into their 80s. Everyone else needs to prudently invest for the future and think about the long term.

This is, of course, easier said than done when human emotions are involved.

One solution to the issue of fear-of-bad-investment-timing is to help clients find an approach that is less sensitive to timing. This approach has two dimensions: what they invest in and how they invest.

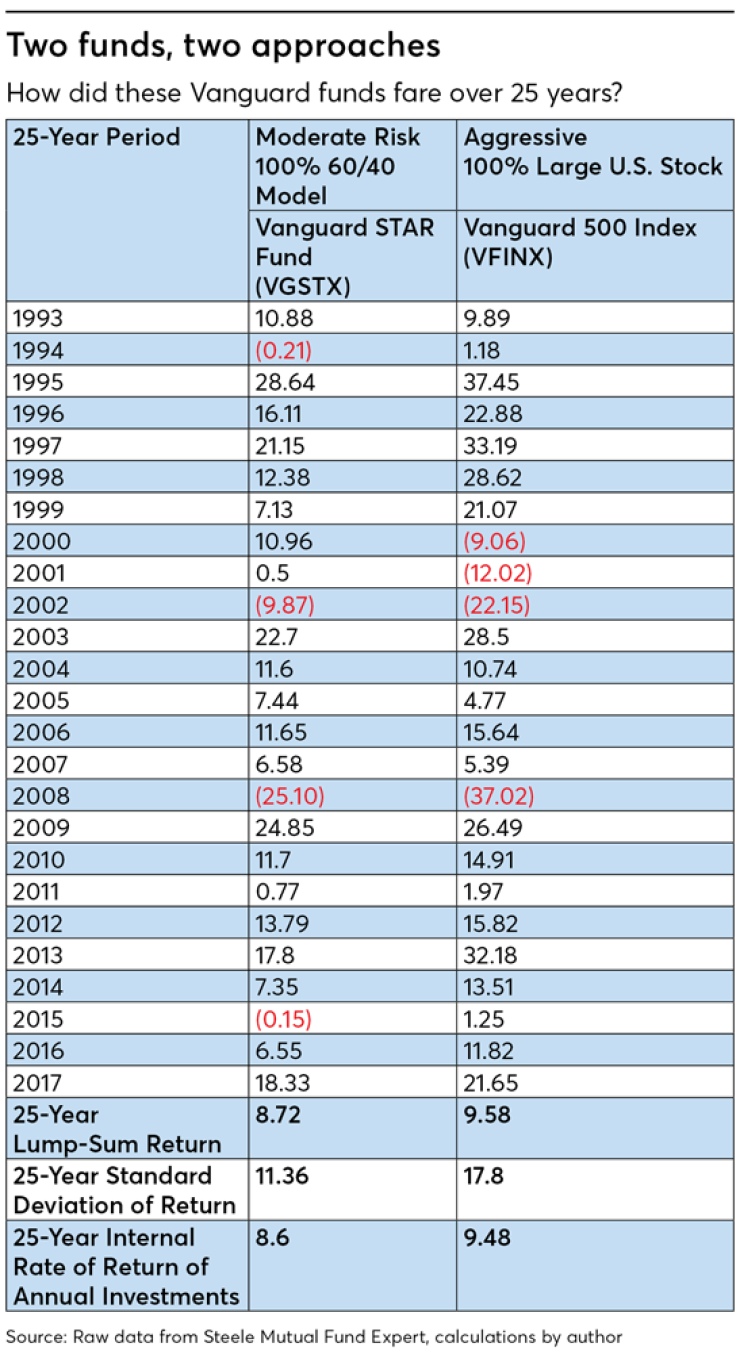

Let’s first talk about what to invest in. To dramatically simplify this discussion, I have chosen two different types of mutual funds (both happen to be Vanguard funds). One fund represents the market as many investors refer to it (although it is not actually a representation of the broad market) — that is, a fund that mimics the S&P 500. In this case, I am using Vanguard 500 Index (VFINX). VFINX has 100% exposure to large-cap U.S. stocks, and uses a market capitalization weighted approach.

The other fund I have chosen is a fund-of-funds, specifically the Vanguard STAR fund (VGSTX). This particular fund invests in 11 other Vanguard funds and is diversified across several asset classes.

Specifically, VGSTX has an allocation of roughly 40% to U.S. equity (with approximately 80% allocated to large-cap U.S. stocks and the balance allocated to midcap and small-cap U.S. stocks), 20% to non-U.S. stocks and 35% to bonds, as well as a small percentage in cash. In general terms, it employs a diversified 60% stock/40% fixed-income approach.

As shown in “Two funds, two approaches,” the outcome for each fund over the past 25 years is surprisingly similar. The 25-year average annualized return for VGSTX is 8.72%, and VFINX has a 9.58% return. However, the path to those outcomes was very different, with VFINX being far more volatile (as noted by the standard deviation figures) and the significant losses experienced in 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2008.

It is precisely that type of volatility that may have caused your client to pull out of equity investments in the first place — and having pulled out during periods of turbulence, they would likely have failed to achieve either the 8.72% or the 9.58% return. VGSTX generated 91% of the return of the large-cap U.S. equity market with only 64% of the volatility. For skittish investors, that is an excellent tradeoff.

The results in the chart “Two Funds, Two Approaches” assume a lump-sum investment at the start of 1993. This is the assumption behind all reported performance data.

What if your client chooses to get off the sideline and back into the stock market gradually by investing money systematically over time, rather than all at once? This technique can reduce risk, specifically what we might refer to as investment-timing risk, which is very likely the concern that is keeping your client on the sidelines.

Rather than re-entering the market all at once, your client can make regular contributions (annually, quarterly, monthly, etc.) over a period of time. In fact, this is how most of us actually invest, whether it be in 401(k) accounts or IRA accounts, etc.

Shown in the last row of “Two funds, two approaches” is the internal rate of return when making annual investments into both funds over the past 25 years — 8.60% for Vanguard STAR and 9.48% for Vanguard 500 Index. These are both very similar to the 25-year lump-sum returns. We now have our benchmark returns for both of these funds based on two methods of investing: lump sum or systematically over time.

Let’s now evaluate a bad-timing scenario in which an investment was made on Jan. 1, 2000 — just before the U.S. large equity market tanked for three consecutive years. This is a theoretical simulation of a client who comes out of cash and re-enters the stock market now in 2018, only to have the market subsequently go into decline for several years.

We find in “Bad start” the results of this sort of “bad” investment timing from a historical perspective. However, that only applies to VFINX, which experienced losses of 9.06%, 12.02% and 22.15%. Vanguard STAR had positive returns in 2000 and 2001 and a loss of just under 10% in 2002. Thus, it clearly matters what we invest in. For nervous clients, the best advice is to diversify, diversify, diversify.

In this 18-year period from 2000 to 2017, a lump-sum investment experienced the brunt of bad timing and finished with an 18-year annualized return of 5.29%. Vanguard STAR fared better, with a return of 6.96%.

Interestingly, if a client chose to invest money each year (say, $3,000) into each fund, the internal rate of return for both funds was impressive: 8.41% for Vanguard STAR and 9.78% for Vanguard 500 Index. The notion of bad timing generally doesn’t apply to clients who invest systematically and plan to stay invested for at least 10 to 15 years.

Moral of the story: Systematic investing markedly reduces timing risk, whereas lump-sum investors are fully exposed to timing risk — at least during the first several years. Clients who get back into the stock market by making regular contributions may actually benefit if markets decline during the first few years.

And if markets don’t decline initially, that’s OK, too. Very simply, lump-sum investors can only feel good initially if their investments have positive returns. Systematic investors can feel good either way — if performance is initially bad, they are accumulating more shares with their subsequent investments. If performance is good, well, they can live with that.

So if you have clients who are nervous about re-entering equity investments, you might suggest they do so gradually. As the saying goes — this is a marathon, not a sprint.