Going independent: What lies ahead?

Every advisor's route is different but one thing is certain — turbulence.

Five advisors in Merrill Lynch's Savannah, Georgia, office made the biggest decision of their financial careers one morning last March: They quit.

A few moments prior, Melissa Bouchillon was delivering a cupcake to a colleague whose birthday she had missed. Now she was crying on her way out the door.

It took about two minutes for Bouchillon’s team to walk to the independent firm they were founding across the street from Merrill's office. They could see their ex-employer from the front window of the new workplace.

There was a lot at stake in this move: their clients, more than $1 billion in AUM, a potential lawsuit and, unavoidably, sleep.

Bouchillon's team has plenty of company on the walk to independence. Since 2014, at least 800 advisors — some of the biggest producers in the industry — have left wirehouses or broker-dealers to join RIAs despite demanding work, stress and uncertainty of not knowing whether their clients will follow.

In 2017, at least 170 advisors departed employee brokerages to join independent practices, according to data analyzed by Financial Planning. Those newly independent planners oversaw more than $31 billion in assets.

More than one-third of wirehouse advisors say they would prefer to join the independent channel should they decide to leave their current firm, according to a 2017 Cerulli Associates report.

But what does it really take to go indie? Is it worth it?

Here's the journey undertaken by advisors like Bouchillon who've successfully made the transition.

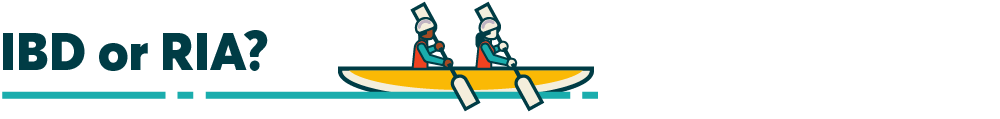

This question may seem perfunctory. It's not.

Experts and independent advisors emphasize it's essential to identify the problem you're trying to fix. Independence may not be the best solution.

“It’s generally rare that someone just wants to do it for the money,” says Paul Foley, an attorney at Kilpatrick Townsend who works with advisors joining or building their own RIAs. “There’s a broader scope of issues.”

Corporate bureaucracy, a bad branch manager and larger firms shunting an advisor's smaller clients to call centers are just some of the factors driving advisors to make a change, Foley says.

Other times it is less about conflict, and more about the potential for growth.

“I felt a little bit restricted in the sense of what I could and couldn’t do, not because the firm wasn’t receptive to it, just because the firm's platform was not built to offer services the way I wanted to offer services,” says Charles Adi, who left a small, boutique firm in Houston to open his own RIA, Blueprint 360.

Before his departure, Adi had built a book of business comprised of young clients, many of whom had recently graduated college or were new to the workforce. Financial education was just as important to them as investment advice, but the firm's compensation structure didn't offer the flexibility he needed to charge a monthly retainer.

“I was providing a huge amount of free advice to my clientele on things like tax planning, student loan refinancing and cash flow management, without getting compensated for it,” Adi says.

For advisor Jim Denholm, it was partly a matter of reorienting his professional trajectory.

|

“I had gotten to a point in my career where I think I was kind of going through the motions,” says Jim Denholm, who left Wells Fargo to open IronBridge Private Wealth, an RIA affiliated with Raymond James based in Austin, Texas. He adds: “I had just kind of fallen into a rut.”

Many advisors cite one reason above all others: Going indie meant being able to put their clients’ interests first, in ways they felt they’d formerly been constrained.

Still, the transition takes much more than just desire — launching a business is demanding.

An indie advisor must also prepare for unexpected expenses that come with operating a company, sudden losses of clients or even lawsuits.

“There’s a specific skill set, a specific mindset that you must possess, because there’s a tremendous amount of risk,” says Ryan Shanks, CEO of Finetooth Consulting, a consulting firm that helps advisors go through the move to independence.

Breakaway brokers need extra confidence, he says. They have to be comfortable with taking risks and be knowledgeable of the requirements.

The advisors will be up against a lot of competition.

“You walk outside and throw a straw, and you’re going to hit a financial advisor. They’re everywhere,” says Denholm.

There’s more than one way to go independent. Which route is the right one depends on what the advisor is looking for: resources or control.

“Larger firms will tend to provide better resources. Smaller firms will tend to provide better customization, so it’s not a one-size-fits-all,” says Jeff Nash, CEO of Bridgemark Strategies, a recruiting and consulting firm.

Some advisors leaving big firms don’t want to give up the convenience of having someone else take care of the day-to-day details that come with running a business. They might choose to work with an affiliate independent broker-dealer platform.

“We utilize all the resources of the wire, but it allows the financial advisor to make the local decisions, as to staffing, real estate, what the client experience will look like,” says Alex David, head of branch development at Wells Fargo’s independent arm, FiNet.

Advisors choosing this route give up an element of control. For example, Wells Fargo provides an approved script an advisor must follow when reaching out to their clients about the transition. Any additions must be approved, according to André Cantareira, practice services manager at FiNet.

Alternatively, opening an RIA provides relatively unlimited flexibility, but requires financial planners to take on a lot of responsibility themselves, whether or not they choose to get assistance. Someone has to pay the electricity bill, choose the furniture and buy the computers.

Advisors Scott Sanders and Jesse Coffee thought joining a pre-existing RIA provided an in-between.

“I didn’t really have an interest in completely starting from scratch. Coming from a big firm, I have expectations,” says Sanders, who left Merrill Lynch with Coffee to join True Private Wealth Advisors, in Salem, Oregon.

He adds: “We have true independence, but we have a very robust back office to support us still.”

|

However it’s done, going independent is a long process.

It takes about six months to make it happen, says the Bridgemark CEO, Nash.

“There’s basically a 350-point list that our team takes people through,” says Jason Pinkham, director of Eastern division and transitions at Dynasty Financial Partners, a firm that has helped 47 teams through the process of opening their own RIAs since 2010.

Pinkham’s team divides the transition process into three pieces: planning, execution and the advisor’s resignation.

Advisors aren’t making these decisions at their desk ― they’re making them late at night, early in the morning or on weekends because they still have a full-time job at their employer firm, Pinkham says.

“If you start truly as an independent, you’re starting at the first inning. When you start with Dynasty, you’re already in the fourth inning,” says Bruce Lee, who opened Chicago-based Keebeck Wealth Management with backing from Dynasty a few months after being discharged from Merrill Lynch.

Capital is crucial, says Jason Inglis, who runs an RIA called ReDefine Wealth Management in Denver.

“We modeled it as if the first three years we weren’t going to make a dime,” he says.

However, it might not always take that long to turn a profit. Sound View Wealth Advisors, the RIA opened by the five advisors in Savannah, Georgia, was profitable in a little over three months, say Melissa and her husband, Kelly Bouchillon, also an advisor.

Advisors have to keep their decision quiet until the day they walk out. Tipping a hand to clients about opening a new firm while still employed by a wirehouse runs the risk of a lawsuit, Foley warns, especially if you’re part of a big team.

Advisors covered by the Broker Protocol can take certain client information with them when they leave: clients’ names, phone numbers, email addresses, home addresses and account titles.

“Account numbers, Social Security numbers, dates of birth, client notes ― any of those kinds of things are not permitted,” Foley says.

Giving in to the temptation to get creative, dropping hints to a client that you plan to open your own RIA, gets into dangerous waters.

“Creativity costs a lot of money, or can cost you a lot of money in court,” Foley says.

Another warning: Don't tell colleagues of your plans.

The Sound View advisors waited to tell their five associates about the new RIA until right after their resignation.

“We didn’t know if they were going to resign at all,” says Melissa Bouchillon, who added that they had to wait outside, to see if they would follow to the new office. It was the longest few minutes of her life, she says.

Sometimes the news of a resignation doesn't go over well with old colleagues, an experience shared by Sanders and Coffee.

“From an emotional standpoint, it kind of felt like we were leaving family behind,” Sanders says.

“There were some tears shed,” Coffee adds.

|

|

|

Which wirehouse offers its advisors the most freedom? Which one offers the least? And do advisors have what it takes to break away? Consultant Rick Rummage elaborates on how many misunderstand the benefits of breaking away. |

After ex-Wells Fargo advisor Jim Denholm resigned, he rushed to his new office to get in touch with his clients ― only to discover the phones were not properly set up.

“I was calling with my cellphone. It felt like the side of my head was about 1,000 degrees,” says Denholm. “We blasted out an email stating what had happened, and that we had resigned and formed our own firm, and that they were going to be hearing for me over the next few days.”

Denholm’s strategy was to call clients he was confident would follow him to the new firm. He gave them the pitch he had been practicing over and over for weeks. After he started getting comfortable, he moved on to the clients with the most assets.

In the meantime, Wells Fargo assigned his clients to former colleagues, who started making calls to persuade clients to stay with the firm, Denholm says.

Wells Fargo and Merrill Lynch declined to comment on the policies set in place with regard to a departing advisor’s book of business. Morgan Stanley and UBS did not respond to a request for comment.

|

Fortunately for Denholm and other advisors going independent, most clients decide to move their assets to their advisor's new firm. Advisors retain an average of 87% of their clients when they transition to an independent model, according to a 2018 Charles Schwab study.

Some advisors say their career move improved relationships with clients. Denholm and Sanders discovered a new sense of relatability with their clients who were business owners. They could celebrate and commiserate about entrepreneurial triumphs and challenges.

“Some people brought us flowers, congratulatory things. I was surprised how excited clients were for us,” Sanders says.

Independent advisors say yes.

A 2017 Cerulli study found that 90% of independent RIAs said they were very likely to remain affiliated with their current firm in the next 12 months. That’s a much higher sense of satisfaction than other advisors expressed about their channels. Only 71% of wirehouse advisors said the same, according to Cerulli. About 95% of independent RIAs say that their current channel is their preferred one.

Tears may be shed, phones might stop working temporarily and FINRA registrations might take longer than expected. But the Bouchillon team, Keebeck, Sanders and Coffee, Denholm and Adi are steadfast in saying they made the right career decision.

“The first year, you have to work pretty hard. You know, it’s a challenge. … There’s a lot of things you realize you take for granted working for a big firm,” Denholm says. “But it doesn’t seem like work. And it still doesn’t seem like work a year into it.

“For people that do have that pull and do have that drive, I think it’s the best thing you could possibly do,” he says.

Toughest thing for RIA founders?

Name their practice

Six Barclays advisors launching their own $3 billion RIA faced their greatest challenge: What to call themselves?

Selecting a custodian, finding office real estate in three cities, choosing new reporting software ― those were easy tasks compared to the struggle of picking a name.

It was a “painful experience,” says managing director Jack Petersen. The team went through more than a hundred choices, says Petersen, recalling one conference call on the subject that dragged on to 3 a.m. The founders actually delayed their July 2015 launch date by a week before settling on the winning name: Summit Trail Advisors.

Thousands of advisors have been through a similarly exasperating experience. Several planners compare it to naming their firstborn child.

“You’ve got to be willing to live with the name,” says advisor Kevin Reardon of Shakespeare Wealth Management. “I’ve seen firms with made-up names or names that squish two words together. I’m just like, ‘I don’t know what that means.'"

While Reardon’s muse was England’s Bard of Avon (the name connotes longevity and quality, he says), other advisors have sought inspiration in meditation, grandmothers, immigrant heritages, sports, mythical beasts, ancient religions, the U.S. Navy, physics and the heavens themselves.

To read the full story, click here.