Conflicts of interest in retirement advice are common, frequently misunderstood by most clients — and some financial advisors — and in need of tougher IRS scrutiny, according to a new study.

The exhaustive, nearly four-year study

The watchdog interviewed officials at five agencies, spoke with a variety of other wealth management industry stakeholders, delved into the key types of conflicts in IRA and 401(k) services, read the disclosures of some 15,000 firms, calculated the impact of mutual fund fees on retirement nest eggs and went undercover as prospective clients speaking to advisors and other professionals at 75 companies.

With more than $18 trillion in 401(k) plans and IRAs — and $195 billion in annual tax expenditures encouraging retirement savings in those accounts — the results of the study carry major implications for advisors across the industry.

"Conflicts of interest are common in investment advice, including advice on transactions involving retirement assets," Tranchau "Kris" Nguyen, the agency's director of education, workforce and income security, wrote in the report. "Financial professionals may favor themselves over retirement investors, some investors over others, or a line of business or product over others, because it financially benefits them to do so. For example, financial professionals may work on behalf of retirement investors who care about how investment or administrative fees affect their investment returns but recommend products that will help the professionals grow their business. Large firms with multiple lines of business and affiliates can often take advantage of economies of scale, but those large firms' business lines and affiliates can also create sources of conflicts."

Some critics of efforts to reduce or eliminate these conflicts in retirement advice through, for example, Labor's rules argue that trying to apply the fiduciary duty to more of the industry's services will instead force businesses to stop providing access to them for many consumers.

Rules like that could mean that "anybody below $1 million is going to get no advice whatsoever" and that "the marketplace will totally abandon the small investor," said Gil Baumgarten, founder of Houston-based registered investment advisory firm

"I can prove to you statistically that bad and conflicted advice is multiples better than no advice whatsoever," Baumgarten said in an interview. "Perfection is not what we should seek. We should be seeking universal availability of better than average advice and quality products. The brokerage business is just a clearinghouse. It's not designed to be fiduciary."

The watchdog's research included some evidence that access to retirement advice declined after Labor's 2016 rule, as well as other findings that the opposite was true. In 2021, 46% of 401(k) plans said they provided investment advice to participants, compared to 36% five years earlier, according to survey results included in the GAO study. On the other hand, representatives from five associations of industry professionals told the watchdog they pulled back services like investment advice for smaller accounts due to the earlier rule.

"One association representative said that the 2016 rule made it prohibitively expensive for professionals to work with smaller accounts, even for rollovers, because of the potential liability cost," Nguyen wrote.

READ MORE:

Sources of conflict

"There are limitations of disclosure as a communication mechanism, including the complexity of the writing and the conflicts and the inability for disclosure to convey the applicability and magnitude of conflicts to a particular retirement investor," Nguyen wrote. "Based on our disclosure review and our undercover phone calls, conflicts can be numerous, complex, and dynamic, which can make it challenging to completely convey them all, and their implications, through a real-time conversation with a retirement investor. Retirement investors have a stake in understanding conflicts of interest in their relationships with their firm and financial professional because conflicts of interest may be associated with lower investment returns."

The watchdog used a readability test on firms' disclosures and found that they were above a college-graduate reading level. Most retail investors "are not aware of payment streams between firms and product sponsors, would never know to ask about them, and therefore are unaware of the consequences that may occur in their accounts as a result of these compensation practices," a state securities regulator told the GAO, the report noted.

"Three behavioral economists we interviewed said retirement investors generally either do not read or understand the financial disclosures that provide information about conflicts," Nguyen wrote. "Two commented that retirement investors poorly understand conflicts of interest."

In their undercover phone calls, the GAO researchers posed as a 60-year-old prospective client with $600,000 in savings in 401(k) and IRA accounts. At least a dozen of the industry professionals they spoke with claimed to have no conflicts of interest at all.

"Discussing conflicts of interests with clients can be challenging for both the financial professionals and the retirement investor," Nguyen wrote. "Based on our analysis of undercover phone call transcripts, such conversations may not be a reliable vehicle for meaningful communication about conflicts of interest. The conflicts of interest and the applicable standards of care limiting them depend on facts and circumstances that may be unknown at the time of the conversation and susceptible to change. Conversations may focus on known, relevant conflicts that a financial professional thinks a retirement investor should be concerned about, of which there may be none."

READ MORE:

Study of mutual fund fees

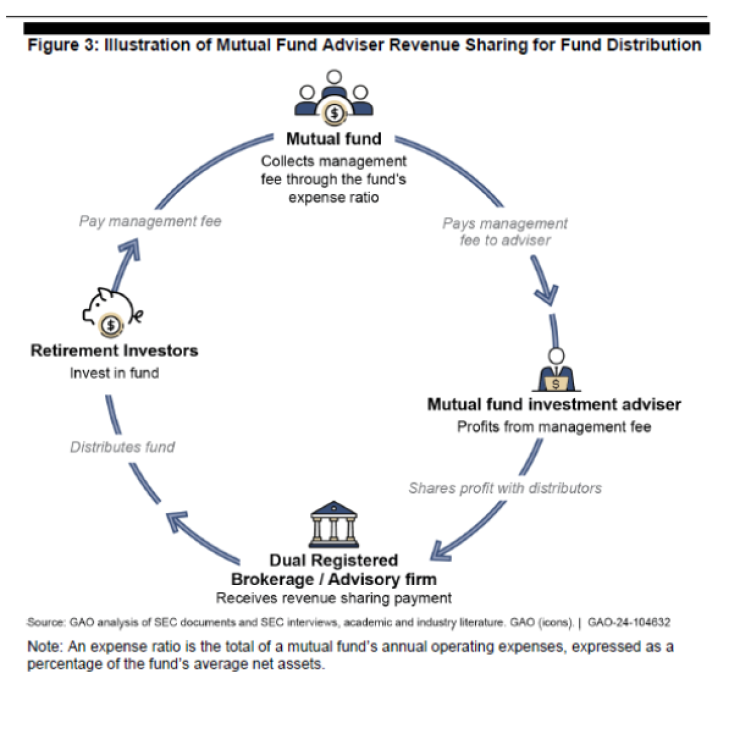

One area those investors ought to take note of is the difference between so-called bundled, semi-bundled and unbundled mutual funds, according to the report.

The bundled funds come with sales-based commissions that are often called "loads" and marketing or distribution expenses called 12b-1 fees. The semi-bundled products don't have those fees, but they may charge other types like platform fees or participate in revenue sharing. The unbundled versions have none of those fees.

Interestingly, the watchdog's analysis of Morningstar data on 28,358 mutual funds' performance between 2018 and 2021 found an association with lower investment returns apart from those fees. On average among actively managed funds, bundled products' returns came in 28 basis points lower than unbundled funds, and, for U.S. stock funds, the bundled funds' performance was 89 bps below the unbundled products. Without even taking the higher fees into account, a hypothetical retirement saver who invested in domestic equities over a 45-year career would amass $55,000 fewer assets during that time, the study found.

"The underperformance found in before-fee returns suggests that [broker-dealer] and RIA

incentives, rather than expected performance, may have been driving investments in these funds during this period," Nguyen wrote.

READ MORE:

Action items at the IRS

Since the Employee Retirement Income Security Act and other federal laws obligate fiduciaries to avoid conflicted transactions or use what are known as "

"Only IRS can enforce the excise tax on prohibited transactions which safeguards the retirement security policy objectives of the federal tax expenditures on IRAs, but IRS has no process to do so," Nguyen wrote. "There are billions in such annual tax expenditures supporting trillions in savings for the retirements of millions of Americans. By developing a process to identify prohibited transactions by IRA fiduciaries and using its enforcement authority to assess the applicable excise tax, IRS can apply appropriate limits on conflicts of interest and ensure it collects any excise tax revenues owed by IRA fiduciaries."

Representatives from the IRS concurred with the report's conclusions and its call for new processes either in collaboration with Labor or through its own means for enforcing the rules.

"IRS agreed with our recommendation for IRS to develop and implement a process independent of DOL referrals for identifying non-exempt prohibited transactions involving firms and financial professionals that are fiduciaries to IRAs and assessing the applicable excise tax," Nguyen wrote. "IRS stated it will examine the processes and consider implementing additional measures to identify prohibited transactions as appropriate. IRS also agreed with our recommendation for the Commissioner of the IRS to coordinate with DOL through a formal means, such as a memorandum of understanding, on non-exempt prohibited transactions involving firms and financial professionals who are IRA fiduciaries and owe excise tax. IRS stated it will explore opportunities to develop more formal means for coordination between IRS and DOL for prohibited transactions related to investment advice provided to IRA owners from financial services firms."