Save enough to be financially independent, and you’re free to chart your own course. That’s the driving principle behind the Financial Independence, Retire Early, or FIRE, movement.

Notwithstanding the challenge of accumulating sufficient assets to FIRE in the first place, FIRE’ing in one’s 40s or even 30s leaves a very long time horizon. It’s so long in fact that the classic 4% rule may be an imperfect guideline, for both good and ill.

With the kinds of extended time horizons that some FIRE adherents face, the key may be to develop more flexible spending rules that can adapt to whatever markets or post-FIRE income may bring. Because while 30-year retirement time horizons have both upside and downside risk, 40- to 50-year horizons invite extraordinary upside potential — presuming the retiree can weather any potential initial storm.

For most of history, retirement simply meant having enough children to farm the land when you were no longer able. Only over the past century or two, with the Industrial Revolution and the move from farm to factory, did the contemporary concept of retirement begin to emerge.

In essence, humans were workers who earned wages to buy the necessities of life, right up until they couldn’t work anymore. And just as obsolescent equipment had to be retired from the factory, so too did obsolete workers.

This meant that saving for retirement was simply about being able to support oneself in that long obsolescence. This in turn led to the creation of safety nets like Social Security to help protect older retirees.

It was only in the mid-1900s that the financial services industry embraced the idea of retirement, and began to define it as a stage of post-work leisure to strive toward. Of course, once retirement is about saving enough to experience that vision, a natural opportunity emerges: to save more, faster and retire earlier.

Thus was born the FIRE movement.

Yet even as the FIRE movement develops strategies to help workers reach financial independence earlier, researchers are finding that even normal retirees often aren’t nearly as happy in that retired life of than they expected. Instead, retirement is associated with everything from the rise of so-called gray divorce — separation rates among those ages 65 or older

In fact, recent research suggests retirees in their 60s actually

Consequently, FIRE is often less about retiring early and more about simply achieving financial independence — which doesn’t mean a life without work, but simply one in which the choice of what to do with your time happens to be independent of the need to generate income.

Retiring early implies a life of indefinite vacation, even though, as retirement guru and former Mercer consultant Anna Rappaport

All of which is incredibly important, because even just modest levels of income can drastically change how much is needed to FIRE in the first place.

The common FIRE rule of thumb is to use the 4% rule, i.e., that it’s

But what happens if the early retiree realizes they will earn an average of $10,000 per year in retirement for the next 40 years? It cuts down the net spending need by $10,000 per year, which reduces the required savings to FIRE by $250,000. And what if the part-time income after financial independence is $20,000 per year? It cuts $500,000 off the required savings.

Granted, the retiree may still need to make this up in their later years, but that’s often a point at which

TIME AND RISK

While the failure to recognize the potential for post-FI income causes many people to save more than they need and wait longer than necessary to FIRE, for those retiring extremely early — and who may have 40- to 50-year time horizons — the safe withdrawal rate isn’t actually 4% in the first place.

The concept of the 4% rule,

Notably, decreasing the time horizon by just 10 years increased the SWR by one percentage point, to 5%, but increasing the time horizon by 15 years decreased the SWR by only 0.5 percentage points, to 3.5%. This would turn the classic 25x post-retirement spending target into a 28x rule instead — or 30x for those who prefer to be a little more conservative.

Notably, the reason the SWR only decreases slightly, even for a much longer time horizon, is that markets themselves tend to move in 10- to 20-year cycles, with extended periods of substantial growth followed by substantial periods of largely sideways markets.

These are the cycles that create

Given bear markets typically run in roughly 15-year cycles, if a withdrawal rate is low enough to survive until the recovery and last for another 15 years, i.e., 30 total, it doesn’t take much more to survive the same difficult period and then last for another 30 years, for 45 total. That’s because the bull market cycles are typically so good that they create more than enough wealth at a modest withdrawal rate to weather the next storm.

In fact, the real challenge of 45+ year time horizons is that they increase the upside potential if returns go well far more than the downside risk if returns are poor. In scenarios where the sequence is not horrific and doesn’t necessitate an initial withdrawal rate of 4% for 30 years — or 3.5% for 45 years — the excess returns above that amount, compounding for 40-50 years, can create absolutely extraordinary upside.

Accordingly, the chart below shows the trajectories of wealth for 50-year retirement time horizons for those who FIRE very early with a $1 million account balance, at a 3.5% initial withdrawal rate from a 60/40 annual rebalanced portfolio, through various rolling return periods in history.

As the chart reveals, it is necessary to use a 3.5% withdrawal rate for the one scenario that is depleting after 50 years at that rate. Yet with a $1 million starting balance, there is a 90% chance of finishing with over $3 million at the end — i.e., only a 10% chance that wealth is anywhere below $3 million — and a 50% chance of finishing with more than $8.3 million left after 50 years, which would still be more than double the starting wealth on an inflation-adjusted basis. In fact, the wealth accumulations are so extreme it’s impossible to see the one failing scenario that necessitated a 3.5% initial withdrawal rate.

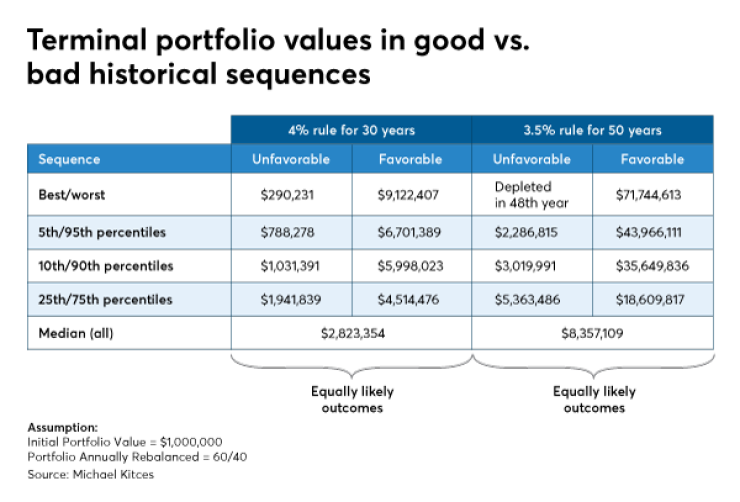

To highlight just how wide the range of outcomes actually are, the chart below shows equally probable percentile outcomes with both a 4% withdrawal rate for 30 years and a 3.5% withdrawal rate for 50 years.

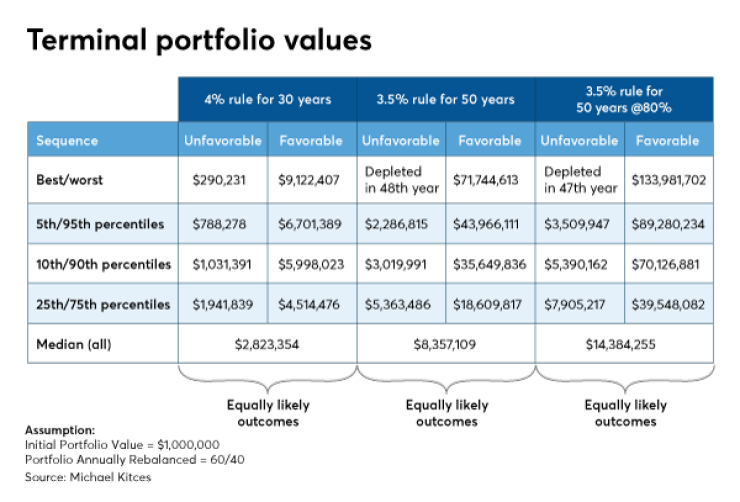

The upside potential is so significant after weathering the initial speed bump of a mediocre first 15 years of returns that the results are even better using an 80% equity portfolio instead of just 60% in equities. Again, one scenario just barely falls short of the 50-year mark — in this case, a 1966 retiree who had to suffer through the challenging ‘70s until the bull market finally arrived — but 50% of the time, the retiree finishes with almost 15x their original wealth on top.

FIRE WITH FLEXIBILITY

The fact that 40- to 50-year retirement time horizons create such a wide range of outcomes, where a $1 million portfolio could either be depleted or finish with over $133 million in wealth left over, suggests that it’s really not enough to just set an SWR and then cruise forward from there.

Yet there’s still that one nagging scenario where disaster may occur — or more realistically, an extended period of poor returns, such as those during the Great Depression or the ‘70s — that can cause even a 3.5% initial withdrawal rate to fail after 50 years. This means any increase in spending, initially or in subsequent years after retirement, must be accompanied by some means to adapt in case a disastrous scenario appears to be playing out.

In other words, the longer the retirement time horizon, the more conducive it is to rules-based spending strategies that change and adapt over time, rather than simply a fixed-anchor spending level that can become extremely decoupled from real wealth accumulation.

RATCHETING RULES

The first option is to consider adopting a ratcheting rule, where a relatively impermeable spending floor is set — e.g., a baseline 3.5% initial withdrawal rate for a 50-year time horizon — but with a concrete target for how spending will be increased if/when a disastrous scenario does not unfold and returns are even merely decent. In other words, like a ratchet itself, spending is only meant to turn one direction, but is locked in the other direction, in acknowledgment that most people find it very distressful to cut something out of their lifestyle once accustomed to it.

One approach to implementing the ratcheting rule is

IMPLEMENTING GUARDRAILS

A second approach would be a guardrail strategy, such as the rules-based spending approach

For instance, rather than setting a fixed 3.5% initial withdrawal rate and only adjusting for subsequent inflation, the retiree might start spending at 4% instead but set guardrails at 3% and 5%. In each subsequent year, inflation-adjusted spending is compared to the value of the portfolio. As long as the then-current withdrawal rate remains in the 3% to 5% range, spending remains on track. If the portfolio rises more quickly and outpaces spending — such that the withdrawal rate falls below 3% — then the retiree gets a 10% raise to their real-dollar spending.

Conversely, if the portfolio falls or simply lags spending increases and the withdrawal rate drifts above 5%, the retiree must take a 10% real-dollar cut. Notably, in Guyton’s original methodology an additional prescription is not to take the annual inflation increase any year that the portfolio’s returns aren’t positive — a small but permanent cut to baseline spending, which also

In essence, the goal of the guardrail approach is to get spending in a protected channel – at least for the next 20-30 years, until the time horizon is shorter and withdrawal rates can naturally drift higher.

SEGMENTING RETIREMENT SPENDING

A third approach to manage the FIRE path more dynamically is to segment the spending itself, effectively combining a ratcheting strategy for a spending floor with more dynamic guardrails for the more adaptive components of spending along the way.

For instance, a prospective FIRE saver might decide to make the FI transition when a 3.5% spending rate against their assets is enough to cover the pure essentials — food, clothing and shelter that you cannot afford to outlive, along with the basic luxuries of life, e.g., some form of transportation, simple entertainment and travel expenses — and then allow any portfolio upside, plus any post-FI work and the income it generates, to cover and enrich the lifestyle along the way.

The key is to recognize that these more adaptive expenses are by definition flexible. They’re the nice-to-haves that in all likelihood retirees will be able to afford in the overwhelming majority of scenarios where there is not a catastrophic return sequence and/or there is non-trivial post-FI employment income.

In the end, arguably the biggest challenge in the FIRE movement is that we haven’t done enough to develop a framework for rules-based spending adjustments — not just to know when it’s safe to retire, but what a safe spending path might look like as the future unfolds.

Yet even with a more accurate initial withdrawal rate, most FIRE retirees will not need to stick with that spending floor indefinitely. Indeed, most will experience some — and in many cases a lot of — upside. Those who are willing and able to be more flexible in their spending actually have the latitude to start with a higher withdrawal rate and spending amount in the first place.

Ironically then, perhaps the definitive problem with FIRE isn’t that the 4% rule is too aggressive, but that it’s too conservative. Either way, the key lesson for planners is that as attitudes toward retirement shift, so too should our approaches toward preparing clients for it, at every horizon.