A barred ex-MassMutual representative and financial wellness entrepreneur who pleaded guilty to fraud received a seven-year prison sentence.

Nearly a dozen victims out of the 23 that Isaiah L. Goodman defrauded for a combined $2.34 million over a four-year span submitted statements cited by federal prosecutors in making their case for the significant term. U.S. District Judge Susan Nelson

He pleaded guilty in February to mail fraud

Goodman “drew all these fancy charts for us explaining different scenarios, recommending different products to us but at the same time he never pushed us too hard,” according to one excerpt from a victim statement included in the government’s sentencing memo.

“Mr. Isaiah made us sign up for additional investment while we were pregnant saying that it would safeguard the future of our children while he was using us to fuel his extravagant lifestyle,” it continued. “He preyed on our naivete. We immigrants from India were easy targets for him because we thought he was like us, someone who is trying to make a living, lifting themselves up from the bootstraps.”

An attorney who represented Goodman in the case and representatives for MassMutual, where Goodman was affiliated with the firm’s broker-dealer between November 2016 and July 2018, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Noting that Goodman admitted to the scheme and helped investigators amass a full accounting of victims and assets for possible forfeiture, the defense’s memo requested home confinement or a term of no more than two or three years.

“Isaiah was unable to reconcile his setbacks and failure to succeed with his need to appear successful,” the memo from Goodman’s attorneys states. “This divergence came to a head in 2017, when faced with financial challenges and difficulties — and the desire to provide for his young family — Isaiah made a terrible and tragic decision to misappropriate client funds to buy his family a home. After that, Isaiah continued down a predictable and slippery slope of stealing client funds to cover different expenses, always intending to repay the funds. Outwardly, Isaiah portrayed himself as a shining success, but the underlying tragedy was accelerating.”

In the months after he was charged, the memo continued, he accepted a permanent bar from the SEC and began working as an Uber and Lyft driver to begin saving money towards the restitution. A lighter sentence or home confinement with a work release would enable the victims to be compensated for their losses more quickly, according to the defense’s reasoning.

Unfortunately for Goodman, though, there were “a number of exacerbating factors” that likely swayed the judge to the longer term, according to Bill Singer, author of the

“The nature of the crime was less poor investment techniques or overly aggressive strategies but outright conversion and misuse of the investments,” Singer says. “As the court found, Goodman took the investment funds and put them towards his home, his cars, his other business venture, and, of all things, a hot tub and a cruise. As such, it's hard for a court to find some mitigation in the sense that Goodman's investment strategy was whipsawed and sandbagged by a recession or a black swan event.”

Goodman, like many fraudsters, used phony account statements to fool the victims into believing their accounts were growing, even though he was stealing their money, according to the court documents. In the quotes from victims included in the government sentencing memo, one recalls Goodman’s “ability to look me in the eye” during a ruse involving a “vision board” exercise he often performed for clients.

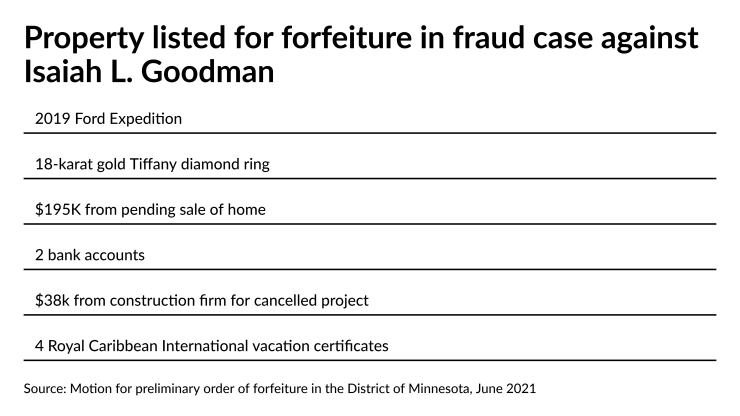

“During one of our sessions — after he’d stolen my retirement money, but well before I knew it — he showed me the colorful slideshow representing his financial dreams,” the victim said. “One photo showed the driver’s seat of an SUV, which the defendant shared he’d been planning to buy. We now know he used victims’ money to buy a Ford Expedition that’s twice as expensive as any car I’ve ever owned.”

Mail fraud charges carry a maximum of 20 years in prison, and the upper range of the sentencing guidelines discussed in the government’s memo extended to more than eight years. As part of the sentence, Goodman is forfeiting real estate and luxury items investigators say he purchased with the misappropriated client money. He’s required to report to the Federal Bureau of Prisons to begin the sentence on Aug. 3.

Firms and regulators may never bring investment fraud to an outright end, according to Singer, who describes it as “part of the human condition.” For the past 20 years, though, he has been calling on financial firms and regulators to create a “Wall Street Antifraud Fund” aimed at ensuring that victims receive compensation if perpetrators are insolvent.

“Sadly, fraud is part of human nature,” Singer says. “As I have long argued, the antifraud fund would pay all proven consequential damages, costs, fees and expenses including reasonable attorneys' fees.”