Female financial advisors have the widest wage gap of all occupations tracked by the U.S. Department of Labor.

Here are 10 things to know about the gap.

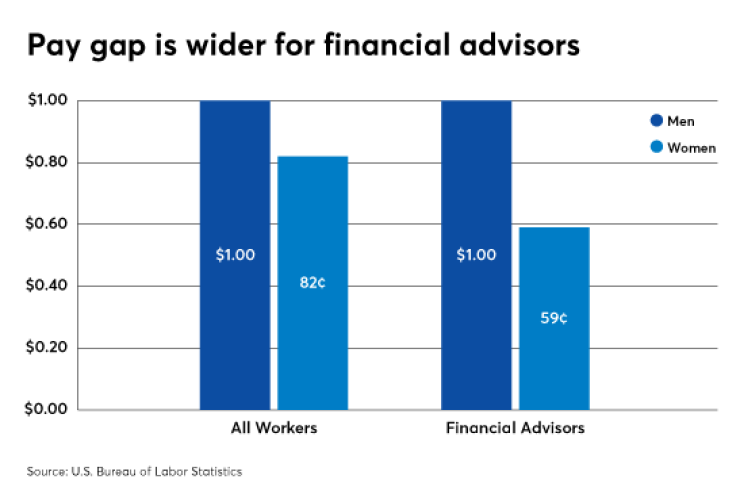

1) The pay gap is huge for advisors. Overall in the U.S. economy, women earned about

Drilling down to specific occupations, though, paints a particularly bleak picture for female advisors: They earned just 59 cents for every dollar their male peers earned last year.

To be clear, that statistic only includes full-time advisors who work 35 hours a week or more, so it’s not dramatically distorted by women who may work part time. The pay measure also includes salaries and commissions, but not one-time payments such as annual bonuses.

2) The gap is persistent. The 59-cent gap for advisors is the widest of all occupations the

These aren’t statistics to be proud of, and the CFP Board wants the disparity to change. Earlier this year, the industry group appointed Kathleen McQuiggan, a wealth manager for Artemis Financial Advisors and longtime women’s advocate, to serve as a special advisor on gender diversity. She describes a “myth of the meritocracy” at financial firms.

“Every firm is claiming to be a meritocracy,” she says, but once firms drill down into their own internal data, they often find a pay gap. She recommends firms adopt more-transparent compensation structures and standardized job descriptions to eventually get the industry to pay equity.

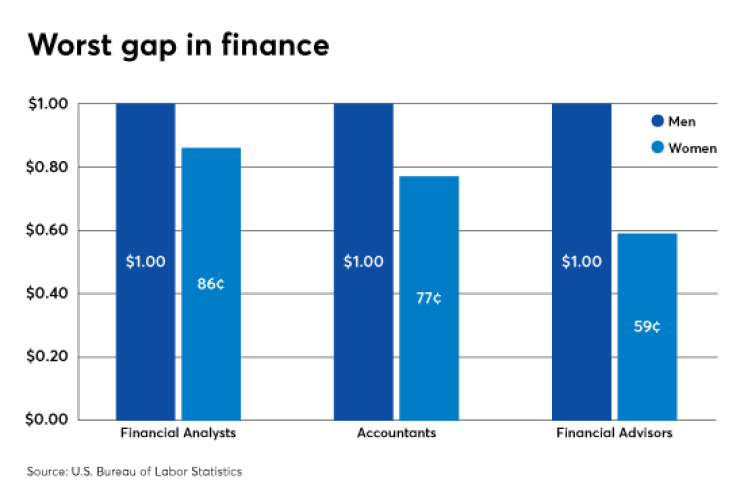

3) It’s better in other areas of finance. While finance, in general, has historically not been known as an egalitarian place for women, other financial professions offer a far narrower pay gap than the advisory route.

Female accountants, for example, earn 77 cents on the dollar, and female financial analysts earn 86 cents to a man’s dollar.

4) Experience and productivity don’t explain it. Maybe male advisors are more experienced than women? Or perhaps they’re more productive?

Nope. Those things don’t explain the gap, either.

Even after accounting for experience, revenue production and ownership status, female advisors still earned $32,000 per year less than their male counterparts in 2013, an

5) So what explains the gap? Business models and differences in compensation structures might be one key factor. While more men work in commission roles, a higher percentage of women are paid on salaries.

Around one in five female advisors were employed by a bank in 2013, compared to one in 10 men. That’s a meaningful difference, because, as McQuiggan notes, “banks and credit unions pay differently than a Morgan Stanley or a big wirehouse. Banks tend to hire more salaried employees versus the variable and commissioned compensation models.”

-

It’s tough enough to grapple with sexual harassment in the workplace. It’s more complex when clients are involved.

March 28 -

From inappropriate touching to belittling comments, women advisors confront workplace environments that are far from welcoming.

March 12 -

The Senator wants to know what the SEC is doing to prevent harassment at banks.

March 5

Indeed, in 2013, 32% of female advisors were salaried, versus 13% of men. When a higher proportion of pay is based on commissions or bonuses, there’s more room for upward growth.

“Women may be more interested in the relationship side of the business, and they may be found less in sales cultures,” says Elyse Foster, principal of Harbor Financial Group in Boulder, Colorado. “If that’s true, they won’t make as much money.”

Among RIAs, women tend to have less experience in sales and as brokers than their male peers, but more background in operations and administration, a

6) Women still are a minority in the industry. As of 2017, women made up only 33% of full-time advisors, the Labor Department data shows — which is about where it was a decade earlier.

The lack of progress looks even direr if you limit the sample to planners with the CFP designation. Women make up only a quarter of CFP professionals — and that number also hasn’t budged in a decade.

Meanwhile, in the RIA space, nearly half of all advisors say they have no female advisors at their firms.

7) Fewer women at the top. Women are less likely than men to be in top leadership roles. About 39% of women owned all or part of their practice in 2013, versus 63% of men, the Aité Group study shows.

And at RIAs, only 20% of firm equity goes to women, the Schwab study shows.

8) Unfair treatment is part of the problem. When advisors engage in misconduct, women are not judged on equal footing with men.

In fact, a 2017 academic study shows female advisors are punished at substantially higher rates relative to male advisors, even when they commit errors that are far less costly. That study, called “

Next on the list were A.G. Edwards & Sons (which is now part of Wells Fargo) and SunTrust Investment Services.

The authors are convinced the study shows evidence of in-group favoritism, meaning men are nicer to fellow men than they are to women. It also could explain part of the wage gap, because when women are punished more harshly than men, they’re also less likely to get promoted or find another job, says one of the authors, Gregor Matvos, a finance professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

When asked about the study, Wells Fargo spokeswoman Kim Yurkovich told Financial Planning that the firm had “substantial issues with the authors’ methodology, data and variables.”

“As always, our focus is on providing a diverse and inclusive work environment, while we continue to serve the needs of our clients,” she said in an email.

SunTrust also disagreed with the conclusions of the report, a company spokesman said.

“We conducted our own review and did not find evidence of bias," he wrote in an email." We have a strong culture of inclusion and commitment to treating our employees fairly and equitably.”

9) Barriers during networking. Erin Hilton, an independent advisor in Austin, Texas, learned to play golf, hoping to fit in better among her mostly male peers and potential clients. But she was dismayed to find out that, at some country clubs in Texas, dining rooms are still restricted to men only.

Whether the barriers to women are that blatant or more subtle, male bonding rituals make it harder for women to network among other advisors and attract high-net-worth clients, she says.

“The cliché of the so-called good-old-boy network in which male advisors take their clients to the bar to drink scotch and make deals while they smoke cigars and pat each other on the back is not far from the truth,” she says. “I am just trying to peek my head into the good-old-boy world.”

Reshell Smith, who now owns her own independent practice in Orlando, Florida, describes how male colleagues at a prior job used to go deep-sea fishing on Saturdays. “Women were not going on that,” she says. “We just weren’t invited.”

As a black woman, Smith says that, when she attends industry conferences, she often goes with the expectation that “I am going to be the only one in the room.”

Like Hilton, she too has learned how to golf — it’s crucial to networking in Florida, she says — but she also puts her own spin on attracting clients. She hosts Money and Moscato wine tastings, which tend to attract more women clients. It’s harder to reach prospective male clients, she says, because she doesn’t fit the typical image of an advisor.

“You would expect that the financial advisor is going to be a white male,” she says. “If there’s a choice, I do believe you’re going to choose a white male. That’s what you’re familiar with. That’s what you know.”

10) Accounts may be passed down differently. In some business models, such as brokerages, it may also be harder for women to have clients passed down from retiring advisors.

In 2002, 17 women filed a class action suit against American Express Financial Advisors, alleging widespread sex discrimination including that the most lucrative accounts were disproportionately allocated to men, whether they were new or passed down from departing brokers. The firm agreed to a $31 million settlement and a consent decree that required the company to create a gender-neutral system for allocating accounts to advisors.

Sometimes processes can be unfair, and at other times, subtle unconscious biases are at play, McQuiggan says.

“Who gets placed on which teams? Who gets access to which accounts? Who gets to sit where on a certain floor? Who gets to pick the inbound calls of the day?” she asks. “I do think there are some subtle inequities, not at all firms, but if you peel back the onion and look at internal processes and systems, we find there are still processes and ways that firms could be more conscious in what opportunities are given to what person.”

There's hope: Some female advisors are optimistic that the fee-only movement and emphasis on the fiduciary standard — even with its status in limbo — could encourage more gender parity in the future.

“Our industry is moving more and more away from commissions and toward fee-based planning, and this could be the wave that catches up women more and allows them into the industry,” says Renée Snow, chair of the financial planning program at UCSC Extension Silicon Valley. “I’m glad that the industry is moving away from a sales mentality, which is not necessarily in the client’s best interest. I think women are going to do very well in that environment.”

McQuiggan also notes two other things that might help: More firms are engaging in internal pay equity audits, and laws in some jurisdictions are making it illegal for employers to ask about compensation history.

“We’ve had this vicious cycle,” she says. “But I think those things are leveling the playing field.”