While non-transparent ETFs will likely entice more active managers into the exchange-traded market, there remain obstacles to financial advisors embracing them. First hurdle? They don’t know them.

“It’s an interesting concept,” advisor Tim Ellis says of the new ETF model. But Ellis, who sits on the investment committee at Memphis-based RIA Waddell & Associates, says he wants more information on how they work before his firm invests clients into one.

He’s not alone.

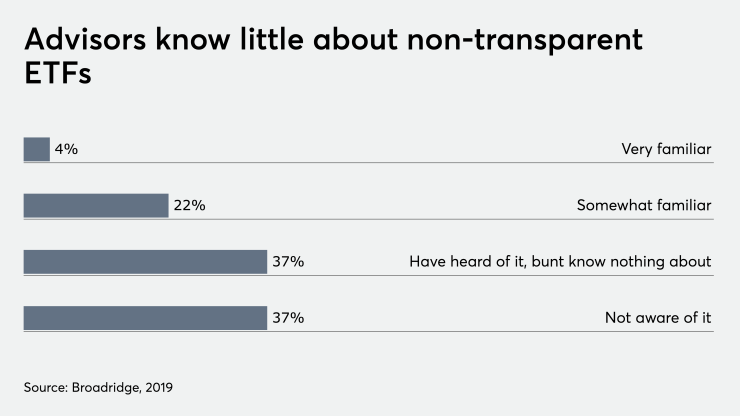

Nearly three-quarters of advisors say they knew nothing about or had never heard of non-transparent ETFs before taking a Broadridge Financial survey in 2019. The technology behind how the funds’ portfolios are valued is “fairly complex,” according to Matt Schiffman, principal of distribution insight at Broadridge.

Still, advisors want to try out these products, according to Broadridge research, which reports that 83% of advisors want their favorite mutual fund to introduce an active ETF product.

The research indicates what lies ahead for non-transparent ETFs, which are the newest iteration of a fund whose popularity has soared over the last decade. ETFs surpassed $4 trillion in assets last year, and their low-cost and tax-efficient advantages have put

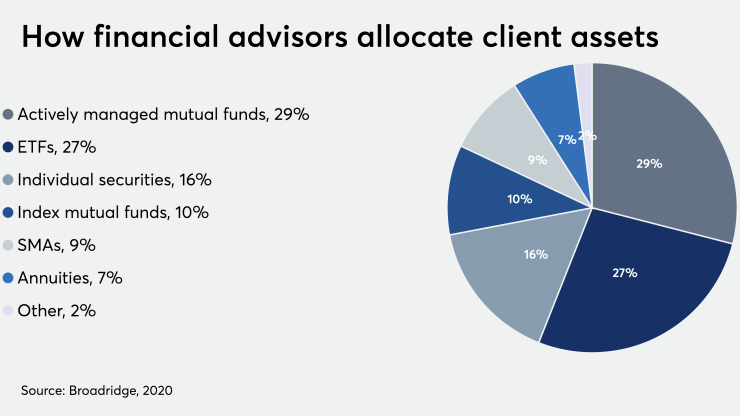

Even so, mutual funds still have more assets. There were over $20.46 trillion in assets invested in mutual funds at the end of April, according to the Investment Company Institute. And actively managed mutual funds, on average, still make up the greatest portion of advisor portfolios, according to Broadridge research.

But since the SEC approved the non-transparent ETF structure at the end of last year, portfolio managers may be eager to try their hand in a market they have been previously reluctant to enter.

“There’s been a hesitancy among investment advisors to set up an active ETF,” says Kip Meadows, CEO of the fund administration company Nottingham, which is helping launch both the Blue Tractor and NYSE’s non-transparent ETF structures.

Portfolio managers spend their careers determining what stocks to buy and sell and how to rebalance their portfolio, he says. They’ve been reluctant to give all that research away for free.

Now they don’t have to.

Under the new ETF structure, portfolio managers have more flexibility in revealing their holdings to the public. They can choose to disclose all, or some, of their holdings on a quarterly, rather than a daily basis.

“We do a lot of calls within the asset management community, and whenever we hit this topic, there's a lot of interest in it,” Broadridge’s Schiffman says.

Ellis of Waddell & Associates says his firm would need to better understand how intraday pricing will work when the holdings aren’t disclosed on a daily basis. “That's the main thing we would want to see before we jumped into one,” he says. “We'd have to do some vetting before we did that.”

Additionally, it takes time for advisors to adopt new products.

ETFs make up approximately

ETFs have faced skepticism over the years, and some

“They have passed with flying colors,” says Sue Thompson, head of distribution of SPDR ETFs at asset manager State Street.

Advisors who were trying out ETFs before the pandemic are investing even more assets now, she says, and about half of the conversations she had with advisors in April were about tax loss harvesting.

Even if they couldn’t control the market, advisors could “show to their clients that they were doing something really positive for them — improving their after tax returns,” Thompson says.

And because of the tax efficiencies, advisors with wealthy clients are expressing more interest in non-transparent ETFs, Schiffman says.

“The more money you have, the higher the tax issues,” he says.