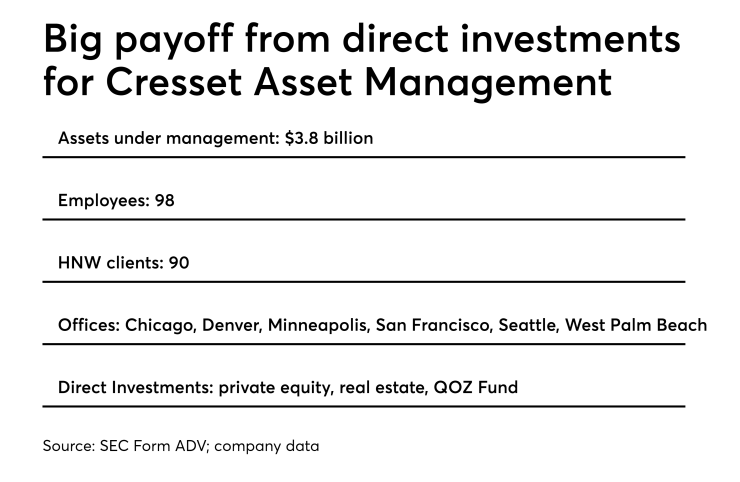

After soaring to over $3 billion in AUM organically in less than two years, Cresset Asset Management has added M&A to its growth engine, snapping up $500 million RIA Evanston Advisors.

The acquisition is part of Chicago-based Cresset’s push to add scale and deepen its reach in its home base as well as in Seattle, San Francisco, Minneapolis, Denver and West Palm Beach, where it already has offices, says founder and co-chairman Avy Stein. Evanston is located in Schaumburg, Illinois, outside of Chicago.

“It’s still a very fragmented market and [acquisitions] will be a very important part of our [growth] strategy going forward,” Stein says.

Until now, however, Cresset’s rapid growth has been propelled by its emphasis on direct investments.

Indeed, raising money privately has become one of the hottest trends in asset management.

Around $2.4 trillion was raised privately in the United States in 2017, according to data reviewed by The Wall Street Journal and Dealogic, approximately $3 billion more than was raised in the public markets during the same period.

“When you give up liquidity, you should be getting a higher return,” says Evanston co-founder Keith Cantrell.

“When you give up liquidity, you should be getting a higher return,” he says.

Private companies have been growing at more than double the rate of public companies over the past 20 years, according to Stein, fueling investor demand for direct investments and an opportunity to achieve what he calls “private alpha.”

However, direct investments in companies usually requires a long-term commitment of around ten years, Stein says.

Illiquidity is the biggest risk for investors, he says.

“You shouldn’t invest [directly] if you need the money in a short period of time,” he explains.

For the time being, “there is a great demand for direct investing” from wealthy families, says industry consultant Jamie McLaughlin.

What’s more, companies who raise money privately, unlike companies who issue public stock and debt, are not required to register with the SEC and provide investors with financial details of their operation.

But Stein says private companies looking for investment capital do in fact provide “incredibly detailed” information to investors in non-disclosure agreements that are “way more in-depth” than what public companies disclose.

For the time being, “there is a great demand for direct investing” from wealthy families “who have no sourcing access or diligence capacity” themselves, says UHNW industry consultant Jamie McLaughlin.

However, even for a firm like Cresset, “it’s very expensive to identify and recruit the talent to do these roles and it takes a very long time to develop access and be part of the private equity ecosystem,” McLaughlin adds.

Cresset Family Office hired industry veteran Michael Cole, who was president of U.S. Banks’ Ascent Private Capital Management for nearly eight years.

To date, Cresset says it has raised around $100 million from clients for direct investments in private equity and real estate deals as well as a QOZ fund that has potential tax benefits for direct investments in “opportunity zones” in areas designated for economic development.

Parent company Cresset Capital Management also shored up its Family Office division last year.

It tapped industry veteran Michael Cole, who was president of U.S. Banks’ Ascent Private Capital Management for nearly eight years, to be CEO of Cresset Family Office. The division, which targets clients with around $50 million in net worth, then hired seven senior executives from Ascent as well as a senior executive from Morgan Stanley Wealth Management.

U.S. Bank filed a lawsuit last fall alleging that Cole gathered confidential, proprietary information before he left the company in order to prepare a strategy for Cresset Family Office. Cole and Cresset have denied the allegations.

-

While the average deal size has climbed above $1.3 billion, solo practices still continue to thrive.

January 24 -

Discounted cash flow valuations have become popular, but untangling the formula can be challenging.

March 15 - What makes for a successful merger? The head of one of the industry’s biggest buyers reveals his secrets.

A federal judge subsequently partly denied a temporary restraining order against Cole and rejected the U.S. Bank’s complaint that Cole had breached his contract with Ascent by encouraging employees to join him at Cresset.

Cresset’s expanded family office team turned out to be a selling point for Evanston.

“About two or three years ago we looked at what clients needed and what we could provide,” Cantrell says. Family office services and “a deeper bench for planning” were high on the list.

Evanston also wanted an opportunity for its staff to have “upward mobility that was difficult to provide in a smaller organization,” he says.

After being introduced by a broker and three to four months of a “fairly intense” courtship and due diligence period, Evanston knew that Cresset’s team, philosophy and “extensive resources” would be a good fit, Cantrell says.

Other suitors, he recalls, “didn’t really have a plan for the future.”