Closed-End Funds: From All Angles

From risk to retirement income, this 10-part series from Financial Planning explores what financial advisors need to know about these funds.

Feature 10

How some CEFs can deliver tax breaks

The one-and-done arrangement for issuing closed-end-fund shares may advantage clients in this area.

By Donald Jay Korn

Closed-end funds can deliver favorable tax treatment to shareholders, but it’s a matter of some finesse. With some dogged investigation, financial advisors may find that the benefits are worth the trouble.

The “closed” in closed-end funds refers to the fixed number of outstanding shares that trade among investors. That stability can provide innate tax advantages, says Dave Lamb (right), managing director in the Global Products Group at Nuveen. And the one-and-done arrangement for issuing closed-end fund shares can help deliver tax relief.

“This structure precludes inflows and outflows,” says Lamb.

Conversely, he points out, if market trends lead to growing redemptions by investors, open-ended funds might have to sell shares to raise cash to meet net outflows. Lamb adds that after a decade-long bull market, some of those sales could produce large realized gains, which would be passed on to investors.

But such forced liquidations might result in unwelcome news for those who hold their funds in taxable accounts, especially if distributions are reinvested. In that case, shareholders would owe real tax on phantom cash flow.

CEFs also may distribute capital gains to shareholders, but Lamb states they are typically less than some open-ended funds might pay out.

TAX-DEFERRED DISTRIBUTIONS

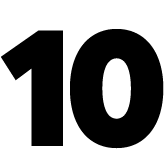

As another example of tax efficiency, Lamb estimates that a majority of equity CEFs uses managed distribution programs to monetize total returns sooner than later. Among the results can be substantial distributions that include untaxed cash flow.

For instance, suppose an equity CEF has a goal of paying out 8% annually to investors via monthly or quarterly distributions. Of that 8%, 3% might come from actual cash flow (net investment income and capital gains), while the other 5% is treated as an untaxed return of capital. This hypothetical CEF might harvest losses to offset realized gains, winding up with few or no net gains that require taxable distributions.

Proceeds from the harvested gains and losses could provide the necessary payout dollars. If the equity fund is delivering an annualized 8% or more, this approach essentially pays out the total returns currently, untaxed.

(As can be seen in the accompanying chart, managed distribution programs among equity CEFs also can result in favorably taxed payouts from long-term rather than short-term capital gains and qualified rather than non-qualified dividends.)

The catch(es)? For one, if this CEF is not earning its targeted 8%, then investors actually are getting some of their money back, perhaps spending dollars they intended for long-term accumulation. In addition, distributing returns of capital reduces the investor’s basis in the fund, which generally results in a larger taxable gain or smaller capital loss, if those CEF shares are sold by the shareholder.

“Basis reduction is always difficult when accounting for investments,” points out Mary Kay Foss, a CPA in Walnut Creek, California. “If there have been return-of-capital distributions that haven’t been tracked, the gain or loss on a sale could be reported incorrectly.”

Thus, it’s vital for advisors and their clients to keep precise records to avoid possible future problems.

SLEEPER TAX BENEFIT

A possible sleeper tax benefit entailing fewer headaches and less tax preparation cost might be result from investing in master limited partnerships through a closed-end fund. The MLPs held by closed-end funds are often companies involved in energy storage or transportation, including pipelines. Payouts can be substantial, including tax-deferred return of capital.

Typically, investors in MLPs receive Schedule K-1 tax forms, which can be complicated and may lead to higher tax preparation costs. Investors in properly structured MLP funds will receive a Form 1099, the usual document for reporting investment income.

“All CPAs hate-hate-hate the K-1 Schedules that you get from MLPs,” says Foss. “A client came to me one year because his former CPA refused to do his tax return once he invested in those MLPs. Not only are these investments difficult to deal with, they often lead to a conversation with the taxpayer to justify the higher bill that results. If CEFs convert K-1s to Form 1099-DIV, I’m all for it.”

Opportunities for tax savings might be found in niche categories. Other specialized CEFs may offer various tax-related appeals to particular clients. For instance, many CEFs hold municipal bonds. Like other types of CEFs, they may use some form of leverage to boost payout rates to investors. “Leverage may deliver more tax-free income,” says Lamb.

Some gold bullion CEFs, including those based outside of the U.S., may qualify for U.S. tax rates no higher than 20% on long-term capital gains, as opposed to like gains from other bullion funds, which can be taxed as collectibles, up to 28%. Savvy handling of IRS requirements might be necessary.

“The 28% capital gains rate is higher than the ordinary income tax rate for a couple with $320,000 of 2019 taxable income,” Foss notes, so such funds might be worth evaluating for high-income clients.

Feature 9

CEFs: A ‘great’ source of yield but beware these nuances

A closed-end fund can provide a steady income stream for clients, but advisors often make misleading assumptions about the regularity of monthly distributions. Here’s what to watch for.

Closed-end funds allow clients to "buy $1 worth of assets at a discount" while reaping higher and more-steady distributions, says Tom Roseen, the head of research services for Refinitiv Lipper.

Still, he warns, there are important nuances. Investors can't always assume those distributions will be made, for example.They also can’t assume distributions will be made at the same rate.

“If your client is looking for steady income stream, closed-end funds are an important asset to provide,” says Roseen in this conversation with Financial Planning’s editor-in-chief Chelsea Emery. But, he adds, “looking at annualized distribution yield, the 12-month yield and the income-only yield, will give them a better understanding of what CEFs can provide.”

Click the play button below to hear the full conversation.

Feature 8

How CEFs can boost clients’ retirement income

Securing optimal returns depends on many factors, including the right underlying asset class and close monitoring.

By Chris Allen

In the eternal quest to secure portfolio income for clients approaching, or already in, retirement, CEFs can play a helpful role — once you vet the tradeoffs.

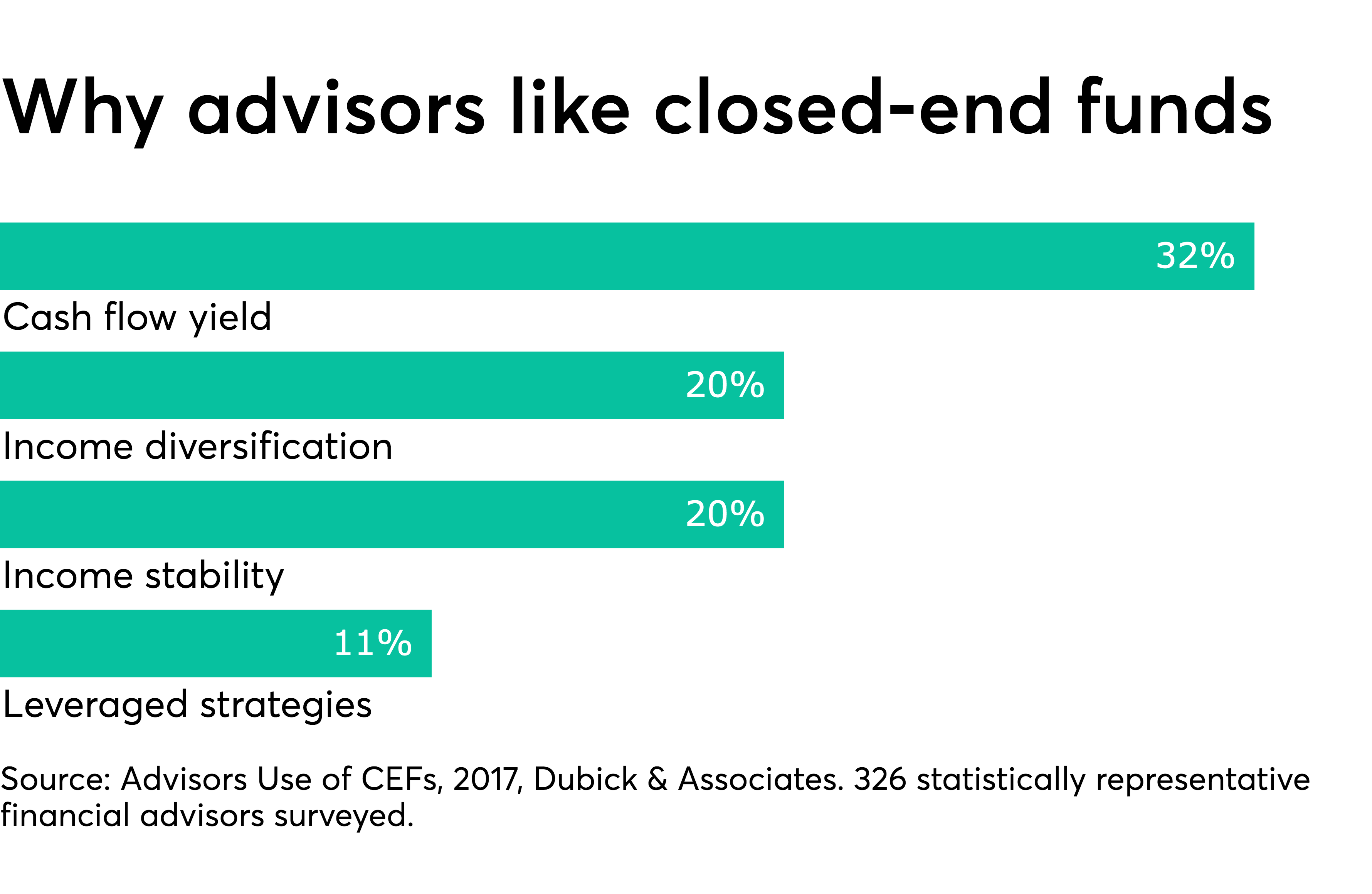

“CEFs have historically been a great source for investors looking for current income,” says John Nersesian, head of advisor education at PIMCO. “Once you’ve retired, high returns aren’t the only goal,” he adds. “Cash flow often becomes a key priority, and CEFs can be part of that mix.”

Retirees stand out as CEF patrons. According to the Investment Company Institute’s 2019 Fact Book, The average age of CEF-owning heads of household is 54, with 37% of the group retired. This compares with an average age of 52 for all U.S. household heads, with 29% retired.

Sangeeta Marfatia, senior closed-end fund analyst at UBS, is upbeat about the potential benefits for seniors. “If you are a retiree and you are counting on monthly income, CEFs may fit perfectly in your portfolio,” she says. But Marfatia also cautions that while CEFs provide exposure to a wide variety of asset classes, they often contain leverage, which means additional risk.

Leverage, which is debt used to buy more assets, is created whenever exposure exceeds 100% of investment capital, according to the CEF Connect website.

“Years ago, during the 2008 financial crisis, I was shocked when I saw portfolios with 40%, 50%, 60% in CEFs,” Marfatia says. “I don’t know what the magic number should be, but it’s probably not 60% of a total portfolio.”

Nersesian further counsels advisors to pay close attention to CEFs’ underlying assets. At the end of the day, she says, the return and the risk is determined by the asset class.

It’s also important to understand the “additional idiosyncrasies” of the CEF market, says wealth advisor Jeffrey Fosselman. “Nothing is rocket science,” says Fosselman, whose firm Relative Value Partners specializes in CEFs and serves many older clients. “It just requires continual attention.”

For example, he says, a closed-end fund may announce an attractive tender offer to shareholders, but garner a tepid response. Historically, tender offer participation — including what Fosselman calls “no-brainer” opportunities — is under 50%, “which suggests there’s a lot of people asleep at the wheel.”

Dorothy Bossung, with Lowery Asset Consulting, likes the potential for enhanced income that CEFs hold for seniors, but acknowledges that comes with “a substantial education process with the client and a certain amount of handholding.”

Fees also may surface as a concern. “CEFs are not known for their low fee structures,” Bossung says. “When you look at the all-in fees on them, they tend to be higher than other [funds].”

Bossung is active in the Investments & Wealth Institute’s retirement management advisor program, which emphasizes “fundedness” with income from “laddered Treasurys, annuity payments, Social Security, pension plans and systematic withdrawal.”

Such strategy provides “more of a guarantee than … anything that is actively managed can provide,” she says. “I still personally believe that CEFs play a nice role, but it’s up a bit in terms of the risk scale.”

If interest rates remain relatively low, Marfatia anticipates strong demand for CEFs from retirees and others. In such an environment, “people are searching for yield,” she says. “You can’t get any decent interest on bank accounts and CDs, so people do look to CEFs.”

CEFs and other income-producing assets serve a dual purpose for seniors, Nersesian says. Beyond cash flow, “they’re intended to help reduce drawdown risk,” protecting other assets during periods of market volatility.

Feature 7

Explore alts through CEFs

Closed-end funds can allow all clients — not just HNW ones — to invest in alternatives

By Chris Allen

Certain portfolios strategies are generally appropriate only for high-net-worth clients. Those with investable assets of $30 million or so are more able to boost diversification and performance by shopping in pricey private markets, for example, and buying alternative assets. However, redemption-free CEFs present an ideal location for alts and make them easily accessible to all clients, not just high-flying elites.

Feature 6

CEF smarts can pay off in a low-rate world

Can more education boost the popularity of these funds?

By Chris Allen

In a world defined by low interest rates, your yield-seeking clients may thank you for your specialized expertise, especially when it’s about CEFs.

In a low-rate environment, “there are not a lot of games in town in fixed income that are attractive,” says Maury Fertig, co-founder of Relative Value Partners. “The quicker the advisor can understand the nuances of the funds, the quicker they can get involved. There are still a lot of funds with double-digit discounts that are trading well under their historical average.”

CEF education is a longtime priority for fund sponsors, though it can be a tough sell. Time-pressed advisors often prefer low-cost, easier-to-research, easier-to-explain products.

For example, Donald Duncan, a managing director of Savant Capital Management now relies on index investments despite extensive prior experience with closed-end funds. “We’ve dialed down CEFs to the extent of extremely little use,” he says.

Other advisors, however, see them as a must-have when it comes to their income earning potential. “There is a trend toward ‘set it and forget it,’” says David Phipps of Phipps Wealth Management, who began using CEFs many years ago after researching the fund structure. “But by and large, studies show that you need a mix with some active management, too.”

Advisors welcome objective education on technical subjects, practice management and timely topics, says Devin Eckberg, chief learning officer at the Investments & Wealth Institute. As the Fed revised its view on interest rates, for example, the IWI offered a CEF webinar that drew a “good response,” according to Eckberg. “CEFs have become a more popular topic today,” he adds.

PRICES VERSUS NAV

Confusion sometimes arises over a CEF’s market price vs. net asset value. The difference typically results in a discount for buyers but could create a premium. Leverage also poses a wrinkle. Most CEFs use it to try to add income, but it also adds volatility.

While most advisors are well-versed in these nuances, some admit they could use a bit more insight. At the same time, all planners should be prepared to explain complexities to clients.

“CEF investors need to, of course, not only understand the moving parts and how CEFs work, but also be patient,” says Mariana Bush, research director, at Wells Fargo Investment Institute.

“And they definitely will need to be able to tolerate the additional volatility of CEFs, because that is one of the risks.”

The reward for learning the CEF ropes is easy access to managed strategies with yields potentially in the high single digits or above. Nuveen-sponsored CEF Connect showed industry-wide CEF distributions as high as 33.5%, with about a third above 8%, as of Sept. 12.

But what if you don’t directly manage investments, CEFs or otherwise? Increasingly, advisors use turnkey asset management programs. According to Tiburon Strategic Advisors, TAMPs

managed or administered over $7 trillion in assets as of 2018.

Scott MacKillop of First Ascent Asset Management says TAMP offerings generally do not include CEFs. “I don’t think advisors or TAMPs are that prepared to explain CEFs to clients,” he says.

|

|

It’s like the whole idea behind the frisbee. There’s physics and velocity and spin, and if you think about it too much, you’ll drop it. Just catch it. |

|

CEF SNAPSHOT

A snapshot of the investment industry shows CEFs had less than 2% of the total $21.4 trillion in US fund assets in 2018, compared with 82% for mutual funds and 16% for ETFs, according to the Investment Company Institute.

Can education grow CEF popularity? Bush, for one, believes it can do that and more. “Just imagine if more people understood CEFs, and therefore be interested in CEFs,” she says. “I think discounts would shrink. If we have enough of those people, discounts may disappear. And that would probably allow the ideal market.”

Fertig sees market behavior as the ultimate driver. “Believe it or not, this is still a corner of the capital markets that is irrational,” he says, “and if you do your homework, it provides some really nice opportunities.”

Phipps dubs himself a “CEF fan.” He suggests sponsors “ramp up” CEF education and “keep it simple.”

“Too often we’re overthinking,” he says. “It’s like the whole idea behind the frisbee. There’s physics and velocity and spin, and if you think about it too much, you’ll drop it. Just catch it.”

Feature 5

3 CEF trends to watch

These shifts in the $275 billion closed-end fund industry are quietly reshaping the customary spreads between market price and net asset value.

By Chris Allen

Attention discount watchers: Three trends in the $275 billion closed-end fund industry are quietly reshaping the customary spreads between market price and NAV.

This means juicy bargains for client income portfolios may not be as plentiful as before, though periods of volatility will likely continue to create spikes of opportunity.

TREND 1: HOW FIRMS ARE ROLLING OUT NEW CEFs

Historically, sales commissions have been paid from the capital raised during the funds’ IPOs. This means early investors wind up paying a premium for share ownership before trading begins, leading critics to say CEF IPOs are “sold, not bought.”

Recently, however, some new IPOs have been set up in such a way that the fund sponsor — not the investor — pays the sales charge, typically about 5% of what the fund raises as its initial capital. Year-to-date as of July 31, this practice has been deployed six times, according to RIA Closed-End Fund Advisors.

“I don’t usually touch the IPOs on CEFs, because I always thought they were kind of a bad deal,” says Kenneth Nuttall, director of financial planning at BlackDiamond Wealth Management (left). “Now, if the investment companies are actually starting to pay the fees, that’s going to be a good thing, because you avoid that whole issue of the 5%.”

Some CEF pros say this could become the new normal — but not all.

“I don’t think it’s the standard,” says John Cole Scott, CIO of Closed-End Fund Advisors. “Right now, different sponsors are trying different things. I envision a future where we come back to maybe smaller loads or work toward a model where we distribute CEFs to the RIA channel and the fee-only environment so there’s no load.”

Scott adds: “I think we’ll be testing a lot of things and seeing what works.”

Some advisors see merit in the sponsor-paid commission approach.

It’s a “good change” because it’s favorable for clients, says Andrew Bloom of B. Riley Wealth Management. “They’re changing their approach to get more advisors to say, ‘OK, I can do that now, because it’s not all about the sales load.’”

TREND 2: SCHEDULED LIQUIDATION

Another feature of newer CEFs is scheduled liquidation at NAV. No longer are these actively managed vehicles — and their typical market discounts to NAV — designed to last forever.

“The new breed of CEF in many instances is coming with a term,” says portfolio manager Ken Fincher of First Trust Portfolios. “The fixed income funds have come with 3- and 7-year terms, and now you’re starting to see equity funds, or balanced funds, with both equity and fixed income offered with 12-year terms.”

The trend caught fire in 2017 when all nine CEF IPOs featured term funds, data from Closed-End Fund Advisors shows. So far this year, four new term funds have been launched, including the BlackRock Science and Technology Trust II (BSTZ) issued in June, which had over $1.5 billion in assets as of Aug. 9 and traded at an 6.79% premium, according to BlackRock.

Still, this idea of non-perpetual CEFs is not entirely new. “There were a lot of term funds in the 1990s, too,” Scott says. “I think they ebb and flow over time. They’re part of the way to stay in the market; part of the way to offer something to investors.”

As a term fund nears maturity, he notes, sharp reductions in yield may occur as portfolio managers start removing leverage to prepare for liquidation.

The upshot: When considering adding — or exiting — a term fund for your client, timing and managing expectations are key.

“The limited-term trend is important,” Nuttall says, citing generally tighter discounts. “You’re kind of getting back to a more normal bond-like structure.”

TREND 3: INTEREST IN INTERVAL FUNDS RISES

Interval funds are also attracting industry attention. These low-profile, unlisted CEFs often feature relatively illiquid assets such as commercial property funds and hedge funds. An interval CEF can sell shares on a daily basis at NAV, but only has to offer quarterly or monthly share repurchases.

“It is becoming harder to bring a CEF to market via traditional channels because most offerings fall into discount territory after syndication support is removed,” says Tom Roseen, head of research services for Lipper.

As of July 31, 10 of the 17 IPOs this year were interval funds, according to the Lipper FundMarket Insight Report, written by Roseen. In 2018, 33 of 36 CEF IPOs were interval funds. “Of the 152 CEFs that IPOed since the beginning of 2014, 105 were interval funds,” Roseen says.

This broadens access to the CEF structure for a range of often illiquid assets. Though interval funds generally lack a CEF ticker on an exchange, they usually have a NASDAQ symbol for identification and performance tracking purposes. This helps advisors research what may be right for their clients.

WHAT’S DRIVING THE TRENDS?

Discount management appears to be the common thread.

In the case of IPOs, a 2018 academic study contends new CEFs start trading at a discount within five months.

“By six-months-post-IPO, the average raw return is -4.75%, underperforming seasoned funds by 8.52%,” according to the study, which was authored by professors Diana Shao, Assistant Professor of Finance at Oregon State University and Jay Ritter, Cordell Professor of Finance at the University of Florida.

Limited-term trusts and interval funds also tend to reduce or eliminate discount-premium pricing. This helps CEFs compete with ETFs and also discourages potential shareholder-activist attempts to unlock NAV.

“This year there’s been as much activism as I’ve seen in several years, meaning you have pressure to liquidate funds, to throw out boards, to have tenders, things of that nature,” says Maury Fertig, co-founder of Relative Value Partners (left).

It remains to be seen whether the latest CEF trends will tighten discounts overall, disarm skeptics and draw more advisors to include CEFs in client portfolios.

Meanwhile, keep an eye on the IPO calendar and watch those spreads.

Feature 4

How a midsize IBD beats the big firms on productivity

SFA Partners uses flexibility and intensive due diligence to power its niche in alternatives.

By Tobias Salinger

A 125-advisor firm that’s partly owned by its representatives is competing — and, in most cases, beating — its much larger rivals in terms of productivity. One factor is its openness to closed-end funds.

The 48th-largest firm, SFA Partners generated the fourth highest average payout per advisor among independent broker-dealers in 2018. Founder Clive Slovin (right) says he has no doubt advisors’ access to a wide range of products helped fuel the payout of $329,000.

The Atlanta-based firm has a niche focus in alternative investments while most IBDs are either shying away or declining to disclose the revenue made from them. And even as REITs, BDCs, interval funds and other alts make up about 20% of SFA’s revenue, it only has one regulatory disclosure on FINRA BrokerCheck after launching in 2003 as the Strategic Financial Alliance.

Interval products are growing more popular with IBDs and RIAs as they give more retail clients a way into alts with some limited liquidity, according to closed-end fund companies. SFA doesn’t sell a lot of them or other closed-end products, but the firm accommodates them in its lineup of funds.

The firm offers robust due diligence and flexibility to fully examine advisors’ suggestions on new products without strict restrictions above existing rules. For example, while SFA advisors place about 20% of client assets in alts on average, the firm doesn’t cap them at 20%, Slovin says.

“It is a much more expensive way of doing business than having immutable rules that result in the transaction just being rejected; that also gives us the opportunity,” he says. “In order to get productivity, you must be able to provide the products that people need. So we do that. It's not the short-term profitability of the company that matters.”

No other firm participating in Financial Planning’s annual IBD Elite study of the sector reported as high a share of its revenue from alts, but 26 firms didn’t disclose any revenue from them at all. The amount reported by IBDs has tumbled by 87% over the past five years to $88.7 million.

In contrast, interval funds — which regularly buy back some of their shares — are rising. They can “improve risk-adjusted returns, capture a yield premium or add low-correlated investments” to a portfolio, Daniel Picard, head of product development at FS Investments, said in an email.

Interval products have amassed nearly $23 billion, according to Jeremy Goff, managing director of social infrastructure at Tortoise, which already has $150 million in its fund after starting it in March 2018. The firm’s offering focuses on schools, senior living and affordable housing assets.

“For most investors, getting access to private debt can be problematic,” Goff says. “We're buy-and-hold. This is not a big trading strategy. It's really about finding good assets and holding on to them as long as you can.”

Some SFA advisors have started using interval funds in fee-based accounts to tap into alts with more transparency in their filings, says Jean Merriman, the firm’s vice president of due diligence and product. Closed-end funds still make up less than 10% of alt assets at SFA, though.

“We treat interval funds just like we treat all alternatives products: We do a deep dive,” Merriman says. “Some other firms will treat them more like mutual funds, and so it's an abbreviated process.”

SFA aims to provide “as close to a one-stop environment as you can get” by enabling its product shelf to contain all offerings that pass due diligence, Slovin says. The firm’s investment committee must approve each new product — which also typically get third-party reviews as well.

Many funds clearly don’t make the grade. While Slovin declines to discuss the firm’s decisions around specific products, SFA reps didn’t sell any of the GPB Capital Holdings limited partnerships currently enmeshed in regulatory scrutiny.

Slovin emigrated from South Africa to Atlanta more than 40 years ago on assignment with Deloitte, where he started his career as a CPA. He later moved into wealth management, working at various BD firms for 20 years before SFA opened 16 years ago.

SFA’s productivity and status as part of a small remaining group of rep-owned IBDs stand out, says recruiter Jodie Papike of Cross-Search. Alts traditionally ebb and flow in the sector and off-the-shelf technology gives smaller firms an opportunity to create robust platforms, she says.

“I honestly love to see it because I do think there is success to be had for midsize firms,” Papike says. “I love to counter this whole concept that midsize firms are going away.”

Advisors own some 40% of SFA. The firm also launched a managing BD named Timbrel Capital in April to help sponsors prepare products for the sector and an alternate corporate RIA called Strategic Blueprint in 2016 for reps who drop their FINRA registrations.

Slovin recalls talking with advisors interested in forming their own BD in 2002. They expressed frustration about firms losing their culture after being acquired by a different company, so he made a promise to them.

“I said, ‘We will build the firm that you can work at and can work for you for the rest of your career, that you will not have to change firms,’” Slovin says. “We started with a core group of five offices. All of those offices are still with us.”

Feature 3

Closed-end funds: A close look at leverage

There’s volatility but also potential long-term gains for clients.

By Donald Jay Korn

When it comes to closed-end funds, clients need a stomach for volatility — and a good dose of patience.

That’s because these investments have characteristics that can be unsettling. For one, many CEFs trade at moving premiums or discounts to net asset value, a factor that can significantly impact shareholders’ returns. Another, perhaps more important, wrinkle is CEFs’ widespread use of leverage. At the end of 2018, at least 332 funds (nearly two-thirds of closed-end funds) were using some type of leverage, according to the Investment Company Institute.

“Leverage in a CEF magnifies both income and the volatility of the fund’s NAV over time,” says John Cole Scott, chief investment officer at Closed-End Fund Advisors, a data, research and investment management firm in Richmond, Virginia. Still, Scott adds, “as long as the cost of leverage is less than the added income from buying more investments, the leverage is positively additive to returns.”

LOOKING CLOSELY AT CEF LEVERAGE

Leverage, for a CEF, may not always be comparable to using a mortgage for buying a home. These funds may use structural leverage, which is generally created through borrowing money or issuing preferred shares, according to Nuveen website CEF Connect. Alternatively, portfolio leverage is created through certain derivative instruments, including tender option bonds, non-deliverable forward contracts, and total return swaps.

|

|

If an investor could deal with the huge swings, this leveraged group would have produced better returns from what many consider the financial crisis market bottom. |

|

This extensive list might seem to indicate a no-holds-barred approach to CEF leverage, but there are regulatory limits. For example, a CEF must have at least $3 in assets for every $1 borrowed (300% ratio) and at least 200% asset coverage for every dollar raised by sales of preferred stock. “If a fund violates these minimums, it won’t be allowed to pay dividends to common shareholders until it sells down debt or preferred stock,” says Tom Roseen, head of research services at Lipper.

Many leveraged CEFs maintain a cushion to avoid going over the relevant limit. “However, if we have a market event that turns the markets south, the higher the leverage, the higher the likelihood that the asset coverage test will be breached,“ says Roseen. “The manager may be forced to deleverage before being allowed to pay out a dividend to ordinary shareholders.” Lenders and preferred shareholders must be paid first.

Deleveraging in such a situation may reduce risk to clients. On the other hand, lower leverage will decrease returns in any subsequent rebound.

HISTORY LESSONS

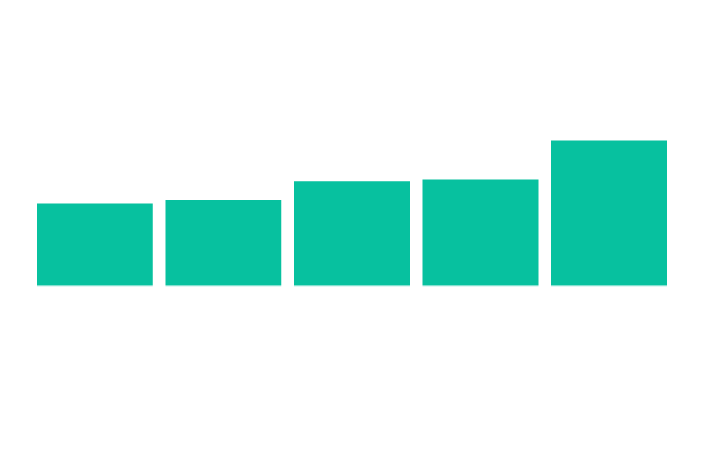

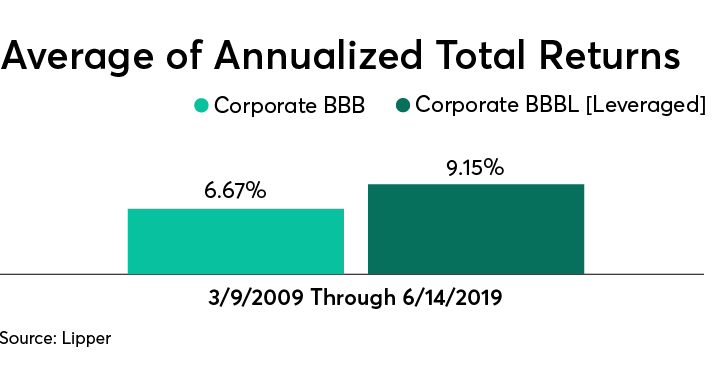

Given all the possible moving parts, how might advisors approach the idea of using leveraged CEFs? Checking results during good times and bad could be instructive. Looking at the 2008 market crash and the 2009 recovery, for example, here are returns for CEFs holding investment grade corporate bonds:

This data shows that leveraged CEFs can be much more volatile than unleveraged entries: Larger losses in a bear market, larger gains in the following bounce-back. The steeper losses made it more difficult to regain lost ground. In this two-year period, the unleveraged fund category had a positive return around 11%, versus about 8% for its leveraged cousins.

But the long-term results tell another story:

“If an investor had a thick skin and could deal with the huge swings, this leveraged group would have produced better returns from what many consider the financial crisis market bottom,” says Roseen. These numbers are from one section of the CEF universe, during a chosen time frame, but they indicate that investors in leveraged funds can do better if they’re willing to make long-term commitments.

BOOSTING YIELDS

If advisors conclude that leveraged CEFs are appealing for certain clients, how can they get their message across? “Advisors can tell clients that a given fund can access cheap leverage in order to fuel higher yields, which is the most common application,” says Scott (left). Thus, CEFs can pay more to investors without the need to pick higher yielding — and generally riskier — investments.

Scott contends that what his firm calls leverage adjusted NAV yield generally is appreciably higher than what investors receive from non-leveraged choices. “Our analysis has found that leveraged municipal CEFs get an extra 1%+ of yield, taxable bond & REIT CEFs get 2%+, MLP CEFs get 3%+ and BDCs get 4%+,” he says. The use of leverage is a “minor risk,” in his view, because most funds have good leverage management.

With hundreds of leveraged CEFs to choose among, advisors can look into past performance, in good times and bad, to see which CEFs really have managed leverage well and delivered higher payouts to common shareholders.

Feature 2

Closed-end funds: More than portfolio income

From housing illiquid assets to relatively low cost of leverage, CEFs have a more varied repertoire than many realize.

By Chris Allen

Closed-end funds are for generating income: It’s certainly a valid selling point when it comes to this $275 billion investment vehicle.

In a low-yield environment, an instrument that yielded, as of mid-July, approximately 6.65%, according to a FactSet data calculation, has its attractions, says Alex Reiss, a director at Stifel. This is one reason why equity-based, total-return-oriented CEF strategies wind up in income portfolios.

And if interest rates continue to stay flat, or go lower, the industry mantra that CEFs are for traditional income may continue to resonate. “Yes, we use them for income,” says Andrew Bloom, of B. Riley Wealth Management, echoing the sentiments of many planners.

But CEFs have a more varied repertoire. In addition to their high-profile role as yield producers, they can also house illiquid assets in a portfolio, because there are no redemptions. Another plus, for investors who want to make use of borrowed capital, is their relatively low cost of leverage, for example, a rate of only 2.38% as of May 31 in a Nuveen muni bond CEF. The ability to enter or exit a CEF quickly, regardless of the underlying assets, also may be helpful.

“There’s more to them than just income,” says Dorothy Bossung of Lowery Asset Consulting (left), who notes her use of Parametric Enhanced Income Core strategy, a managed account that uses equity and bond CEFs.

But there is a hurdle: getting their complexities across to clients.

Bloom tries to clarify that CEF income may comprise interest payments, dividends, realized capital gains and return of capital. He goes on to explain that monthly or quarterly distributions may be “managed” for consistency and that CEF shares usually sell at a discount, but sometimes a premium. “I also have to explain how it’s possible that a [closed-end municipal bond fund] can yield 4% tax-free — well, because it’s 40% levered,” adds Bloom.

CEF LANDSCAPE

In addition to the benefits, it’s also important that clients understand the potential downsides of the product — especially since 90% of CEF shares are owned by retail investors, estimates Patrick Galley, CFO of RiverNorth Capital Management.

More than one-third of the U.S. CEF landscape is made up of equity funds — 36% of the total 506 at year-end 2018 — while the remaining 64% were bond funds, according to the Investment Company Institute. That’s down a few percentage points since 2008, also according to the ICI. Equity CEFs may have lost ground due to the popularity of equity ETFs, says Maury Fertig, co-founder of Relative Value Partners. CEFs are better suited for income assets, he says, “but we use several of the equity funds as well, where we think there’s an opportunity.”

“Some investors will look at a CEF with a managed distribution with a high dividend and just buy it for that,” says Fertig. “They see a fund with a 15% distribution, or 12%, and they don’t fully understand it, but they’re happy to buy it. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.”

Many investors look at CEFs and “think yield” because “almost any strategy, when put into the CEF format, is going to look ‘yieldy,’” says Reiss. That’s because the Investment Company Act of 1940 requires CEFs to distribute realized gains, dividends, ordinary income, preferred dividends or any cash flow that comes into the fund.

|

|

Almost any strategy, when put into the CEF format, is going to look ‘yieldy.' |

|

Caution is advised when CEF shoppers strictly pursue yield, because those enticing distributions often come with higher costs, fees and risk.

“The investor’s perspective of CEFs are for income ends up probably being a large driver of the inefficiencies in the CEF space from a discount-premium standpoint,” Galley says. “Those investors that own them love them when there’s no volatility. ... But when there’s volatility, and everybody starts running for the exit, the supply and demand dynamic changes and there’s more sellers than buyers.”

FOCUS ON VERSATILITY

But Ken Fincher of First Trust Portfolios says educating the client about the versatility of CEFs may go a ways toward solving this problem.

“We try to turn equity portfolios into bonds ... instead of saying we have something else to offer here. We have to make them see a little bit further beyond the yield, and of course the discount, and really have them look at total return.”

Looking to the future, Bossung sees a role for CEFs.

“You’ve got to find something that works for you,” she says. “I don’t think it’s right for everybody, but it definitely has its place in some portfolios.”

Bloom agrees. “I say a little bit of this can’t hurt. It’s almost like an alpha to income.”

Feature 1

The challenges of explaining closed-end funds to clients

Help them understand distinctive features, especially pricing and leverage.

By Charles Paikert

Given the wide range of complex financial options, clients need all the help they can get. That means financial advisors may need to brush up on some asset classes that aren’t currently in the spotlight.

For example, closed-end funds aren’t a top-of-mind portfolio selection for many clients — although they hold about $275 billion in assets. But these funds can help clients achieve diversification and come with a reliable and attractive income stream and the potential for appreciation.

There are misconceptions about some of the more distinctive features of the asset class, however.

The use of leverage is commonly misunderstood, says Devin Ekberg, chief learning officer for the Investments & Wealth Institute. “Closed-end funds can introduce leverage in ways that mutual funds and others can’t,” he says. “For many people, the thought of funds using leverage triggers memories of banks in 2008 and the financial crisis. But that’s not the right way to view it.”

Levels of leverage used by CEFs “are much lower than what people might expect — usually not more than 30%,” Ekberg points out. According to the Investment Company Institute, the average leverage ratio for bond funds stood at 28% last year; for equity funds the leverage ratio was 22%.

Unlike open-end mutual funds, closed-end funds can use leverage to widen investment exposure and potentially boost returns, borrowing at rates pegged to LIBOR or the fed funds rate for taxable funds and the SIFMA index for tax-exempt municipal funds.

Because CEFs don’t continuously issue or redeem shares, they can remain fully invested, don’t have to hold large amounts of cash and have more freedom to use leverage, potentially resulting in higher returns.

“The extra risk closed-end funds are taking with leverage can certainly benefit investors on the upside, but of course they can be penalized on the downside if things don’t work out,” says Josh Duitz, senior vice president of global equities at Aberdeen Standard Investments. Consequently, advisors should make sure clients understand the risks, Duitz says.

Closed-end funds’ use of leverage can be relatively safe “if the underlying assets are of high quality and have volatility of around 3% to 4%, commensurate with stable assets such as high-quality bonds,” says Nathan Sonnenberg, CEO of Wealth Management Consultants in Tysons Corner, Virginia.

Funds investing in short-term, high-quality fixed-income such as municipal bonds or investment-grade corporate bonds can usually take credit risk out, Sonnenberg says. But he warns that high amounts of leverage used in funds investing in master limited partnerships or real assets “can be a toxic, dangerous combination.”

PRICING ISSUES

Closed-end funds have a unique pricing mechanism that may hinder some advisors from using them in portfolios while prompting others to take a risky approach.

Unlike mutual funds, CEFs don’t issue new shares after their initial public offering. When shares trade, their price is based on the net asset value of the portfolio. But demand may be greater — or less — than the actual value of the underlying securities. When the purchase price is valued above the NAV, it trades at a premium; when it’s valued at less, it trades at a discount.

“Because of the fluctuations of premiums and discounts, advisors think that closed-end funds are about market timing, but they’re not,” says Ekberg. “For most advisors’ clients, the priority should be distribution of income.”

For clients who can't afford access to a hedge fund, a closed-end fund may be an option, says Ben Webb, director of manager selection, Balentine.

For clients who can't afford access to a hedge fund, a closed-end fund may be an option, says Ben Webb, director of manager selection, Balentine.

Simply trading at a discount is not a reason to pick them for client portfolios, says Ben Webb, director of manager selection at Balentine, an Atlanta-based wealth management firm.

“Buying a CEF at a discount adds one more risk to the investment, Webb says. “It may sound good, but there is not always a clear reason why a discounted price will close [to the value of the assets in the fund].”

INCOME BENEFITS

Once a closed-end fund is purchased, advisors should help clients monitor distribution of income.

Because CEF managers aren’t subject to the redemption pressure faced by mutual fund managers, they are not forced to buy or sell when they don’t want to, Duitz points out. As a result, advisors can help clients “plan how much income they will be receiving over a period of time,” he notes.

What’s more, the ability to distribute returns more equally throughout the year makes income more predictable and can help clients manage their taxes more efficiently, Ekberg points out.

But income is not guaranteed for the life of the fund, according to Duitz. “There is a market risk that comes with the underlying investments in the fund,” he says. “If the value of an underlying asset goes down in the market, the fund’s dividend can be cut. A CEF is not an income stream for perpetuity.”

|

|

The biggest risk investors face is a closed-end fund that is not managed well. |

|

Advisors should also keep in mind that closed-end funds’ ability to purchase illiquid assets is another reason the funds can generate higher yields.

Indeed, a good closed-end fund can mimic investing strategies used in limited partnerships and hedge funds.

“For clients who want access to an MLP or a hedge fund but can’t afford it, a closed-end fund may be an option,” says Webb. “It can be a tool on the liquidity spectrum for advisors.”

But the freedom to invest in illiquid assets comes with caveats.

“The biggest risk investors face is a closed-end fund that is not managed well, where managers are overpaying for assets and not handling risk well,” Ekberg says. “Advisors should evaluate a fund’s track record, its underlying holdings and the composition of its income distribution.”