"You could not have started the firm at a more challenging time.”

A fraught year seared into the national memory also gave rise to a new sector of financial services.

The rise of the Class of ‘68

The independent broker-dealers born during this fraught year have thrived. Now, however, their role in creating today’s independent advisor threatens their ability to survive another half-century.

By Tobias Salinger

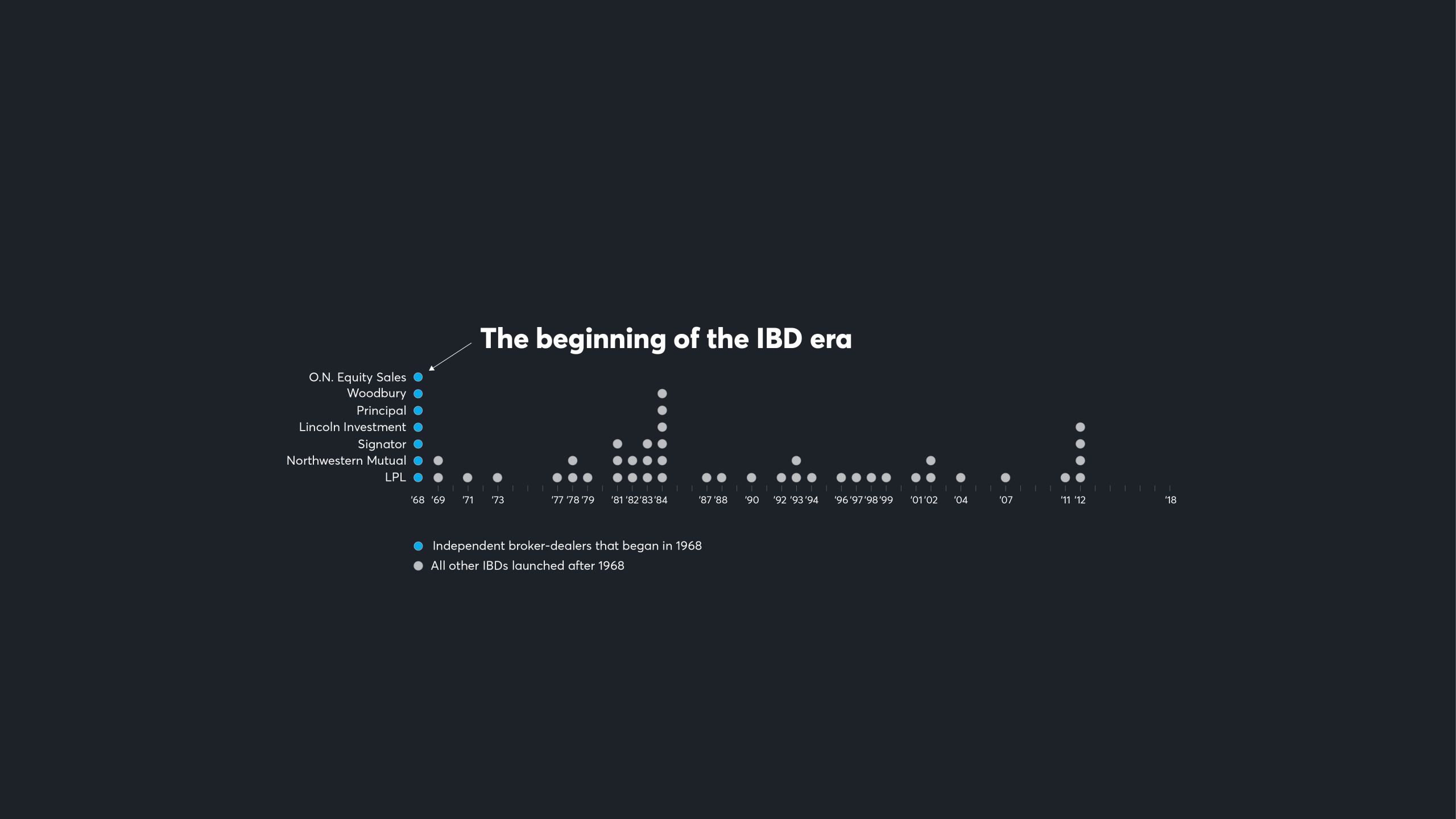

Amid the war in Vietnam and the discord at home in 1968, seven companies were planting seeds that would blossom into today's independent broker-dealers.

It was a tricky time to launch a new financial venture. Fighting in Southeast Asia, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and other violence at home preceded a period of economic turmoil marked by inflation and stagnant equity returns.

"You could not have started the firm at a more challenging time. It was a stunning accomplishment just to survive the first 15 years," says Lincoln Investment Planning CEO Ed Forst, the son of the IBD's founder, Nick Forst.

Yet the era also paved the way for a new form of financial services. A group of insurance firms based largely in the Midwest created a sector of wealth management that today produces more revenue than the gross domestic product of 85 countries.

The IBDs that form the Class of '68 have been major drivers of that growth. Lincoln and the firms now known as LPL Financial, Northwestern Mutual, Signator Investors, Principal Securities, Woodbury Financial Services and O.N. Equity Sales racked up $6.6 billion in combined revenue in 2017. Compared with total revenue of the industry's top 50 IBDs, the Class of '68 brought in 26% of last year's $25.7 billion.

With prescient business strategies, smart mergers and some luck, these companies have survived to celebrate their 50th year. Compatriots that didn't evolve have disappeared.

"It's a business that's been changing since the moment I got in it, and I don't think it's ever going to stop changing," Forst says.

Can these firms survive another half-century?

In an unforeseen twist, they may have helped create the peril themselves with their major role in the emergence of two very recent inventions: the mass-affluent investor and the independent financial advisor. Already, the IBD landscape next year will include at least one fewer member of the Class of '68.

'Shattered America'

Smithsonian magazine called its retrospective on 1968, "The Year that Shattered America," citing events such as the Tet Offensive, the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and the murders of King and Kennedy. Few alive at the time would disagree.

The year of violent political upheaval, however, coincided with massive defense spending. This helped boost the Dow over 1,000 for the first time in January 1966 as strong equity returns from '62 to '68 attracted more Americans to mutual funds and other investments.

Even after subtracting pensions, U.S. households placed nearly 38% of their financial assets in equities by the fourth quarter of 1968, according to Ned Davis, senior investment strategist with Ned Davis Research.

Equities would not reach that level again until the dot-com boom.

"In 1968, despite a divided country, rising inflation and interest rates, people believed the business cycle was conquered," Davis says. "People began to believe that stocks always go up in the long run at some 9% to 10% per annum, so why would one not want to invest in mutual funds rather than cash or insurance? So by late 1968, households were in love with stocks."

Total net assets held in U.S. mutual funds soared by 180% during the 1960s to more than $47.6 billion by the end of the decade, with over $45 billion in long-term equity funds, according to ICI.

The number of available mutual fund products also more than doubled between 1965 and 1970 to 361 funds. Mutual fund assets would reach $18.7 trillion across nearly 8,000 funds by the end of 2017.

Seeing opportunity, insurance companies sought to tap into Americans' growing appetite for mutual funds. They set up distribution channels for their products in the form of brokers who have evolved into today's advisors.

IBDs provided the means for advisors to run their own practices and take higher payouts. Independence has become "a much more mainstream option" due to pioneering advisors at IBDs and RIAs, says Kenton Shirk, director of wealth management research and consulting at Cerulli Associates.

The popularity of mutual funds and introduction of full-scale planning also fueled the ascent of IBDs, says Financial Services Institute CEO Dale Brown.

"You had financial advisors who came from either the wirehouse side or the insurance side of the business who really wanted to offer a more holistic financial planning relationship to their clients," Brown says. "It fueled an entrepreneurial nature that was present in a lot of financial advisors."

Founding stories

Against this backdrop, the modern IBD sprang up.

The year of 1968 produced more members of Financial Planning's FP50 ranking of the largest IBDs than any other single one. Only 1984 came close to matching '68 with six firms' launch.

Two of the companies began in Boston, including a brokerage created by seven insurance companies called Life Insurance Securities Corp., or Linsco. The venture merged with Private Ledger in 1989 and became longtime No. 1 IBD, LPL.

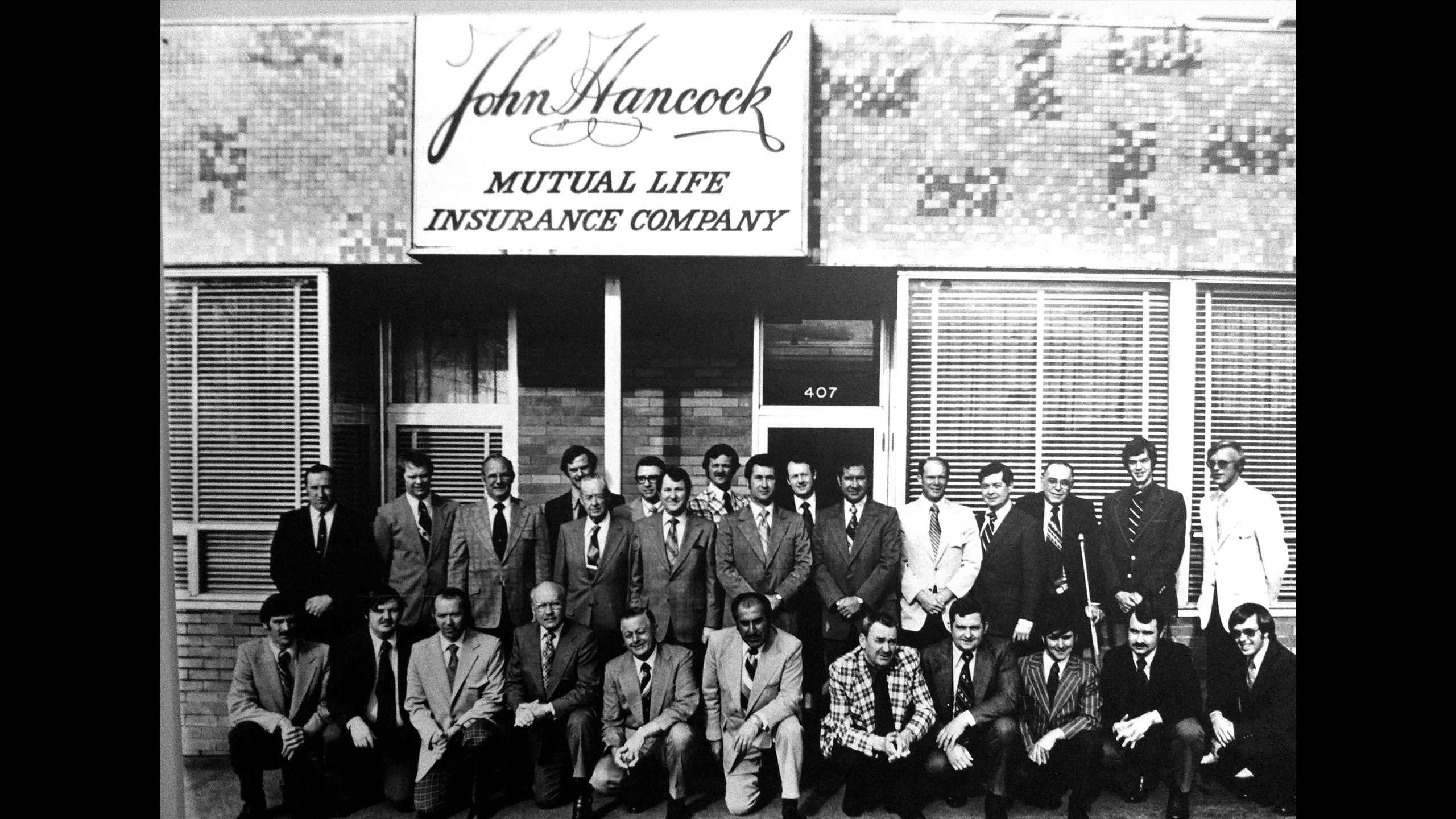

John Hancock's Signator Investors also traces its origins to Boston. The firm, the No. 16 IBD, was known as John Hancock Financial Network until it rebranded itself as Signator in 2013.

Overall, however, the seven firms reflect the variety of the space. For example, Forst's father opened Lincoln Investment Planning, the No. 21 IBD, near Philadelphia to serve teachers and other middle-class clients.

A 1969 contract between the School District of Philadelphia and Lincoln is still in place. The firm offers annuities, mutual funds and advisory services, and has started working with high-net-worth clients. Lincoln remains family-owned and run.

"My dad was quite the innovator," Forst says. "He was very practical, but he was an innovator."

Four of the seven firms came out of the Midwest. In Des Moines, Iowa, Bankers Life Equity Services launched a BD now called Principal Securities to sell its mutual funds through independent agents. Ohio National Life Insurance set up O.N. Equity Sales, or Onesco, in Cincinnati for distribution of its variable annuities.

The BD that would later become Advisor Group's Woodbury Financial Services started by offering the St. Paul Cos.' variable life insurance, annuities and mutual funds out of the Twin Cities.

"Our story is the story of a firm that's been able to transform itself as client needs shifted and advisor preferences shifted in terms of how they run their practices," says CEO Rick Fergesen.

Woodbury and other Advisor Group firms now strive to be "leaders in the fiduciary era," Fergesen continues, noting his firm's original business model of selling insurance products. "That's a big change if you think about it - going from a life insurance distributor to a leader in the fiduciary era."

The seventh firm, Milwaukee-based Northwestern Mutual, noted that the insurance giant was founded in 1857. But after being presented with regulatory filings showing the firm's IBD, Northwestern Mutual Investment Services, launched in 1968, the firm issued a statement about the anniversary.

"Fifty years ago, we began empowering clients to plan for every stage of life by creating [NMIS]," said spokeswoman Betsy Hoylman. "It enables clients to integrate insurance and investments to build an achievable, flexible financial plan so they can enjoy life every single day."

Consolidation then and now

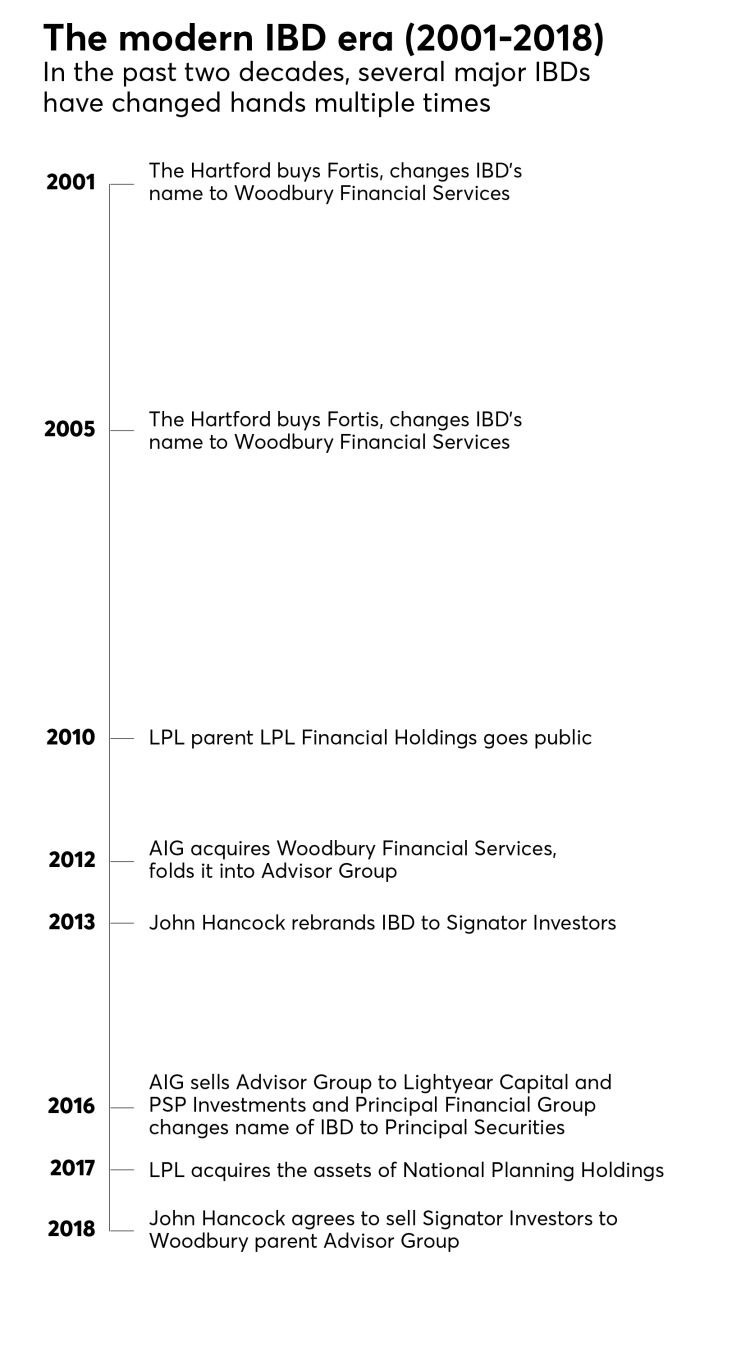

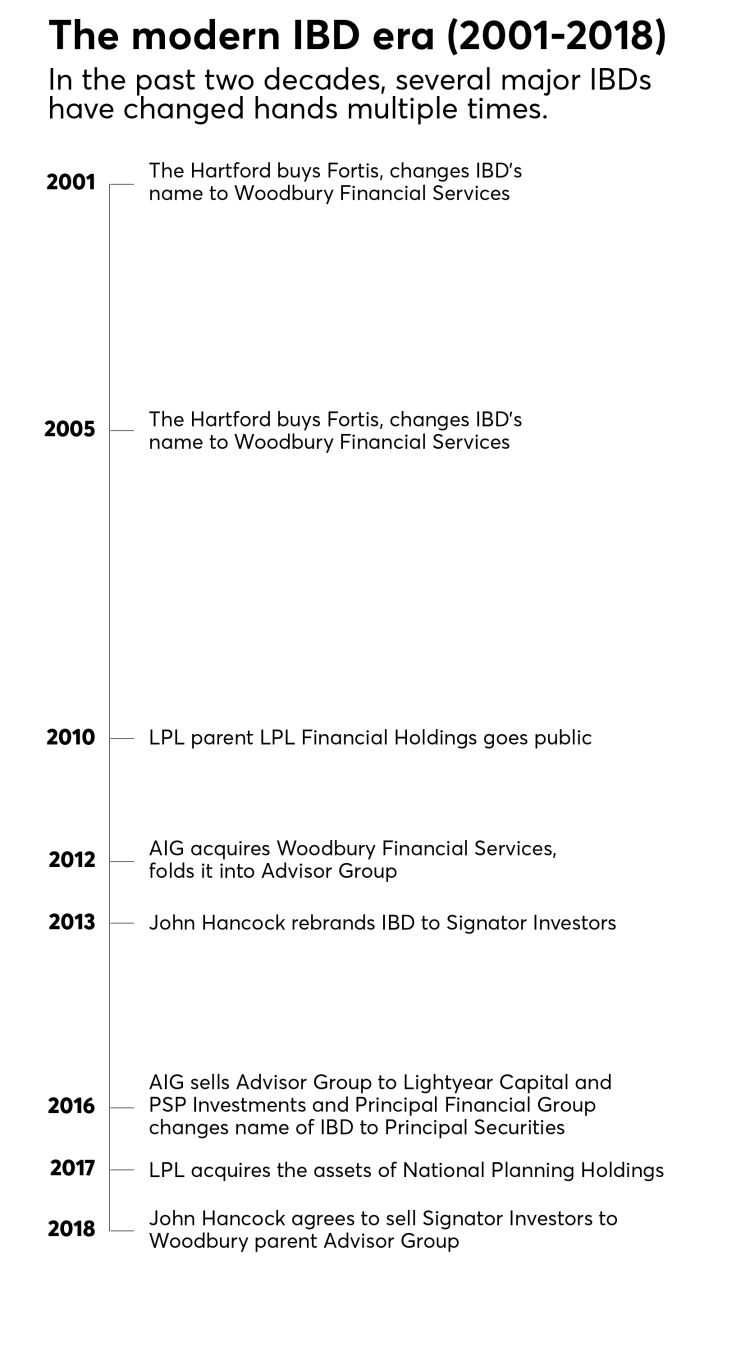

A common thread runs through the class of '68: Consolidation. Savvy, strategic deals have helped them survive and grow while, in some cases, morphing into new firms or vanishing into others.

LPL forerunner firm Linsco started as a brokerage for mutual funds. Later, longtime CEO Todd Robinson merged Linsco with San Diego-based Private Ledger. Nearly 30 years later, LPL has developed into a 16,000-advisor firm with nearly $4.3 billion in annual revenue.

Deborah Danielson joined LPL forerunner Private Ledger in 1982, and she’s been with the same broker-dealer and its descendant ever since.

Deborah Danielson joined LPL forerunner Private Ledger in 1982, and she’s been with the same broker-dealer and its descendant ever since.

"At that time, there was no such thing as financial planning in the public mind," says LPL spokeswoman Rachel White. "It was uncommon to offer insurance and securities together, and wirehouses did not support insurance sales, meaning traditional stockbrokers were unable to offer a full suite of financial products."

While Woodbury's history stretches back more than a century, its genesis as a powerhouse IBD began in 1968. That year, St. Paul Cos. launched it out of a life insurance firm called Montana Life it had purchased 11 years earlier.

More big changes occurred in 1985 when Dutch insurer AMEV purchased Western Life and changed the IBD's name to Fortis Financial Group. Later, the firm took on its current name of Woodbury, after the suburban Twin Cities location of its then-headquarters, when the Hartford bought Fortis in 2001.

The firm has "transformed itself at least twice," says Woodbury CEO Fergesen, adding that the first phase came when it expanded its service offerings under the Hartford. The second phase occurred after then-Advisor Group parent AIG purchased Woodbury in 2012 and added it to the IBD network.

"When we became part of Advisor Group, that really gave us the scale to make us competitive," Fergesen says. "That gave us this huge jump forward in terms of what we could offer advisors in advisory and technology."

The firm's advisory assets under management have reached $5.8 billion this year from just $100 million in 2001. The 1,200-advisor firm's revenue topped $285 million in 2017, making Woodbury the No. 23 IBD with nearly triple its annual revenue of $97 million in 2001. LPL and Woodbury have both helped fuel the consolidation trend in recent years.

Woodbury completed the acquisition of Capital One Investing's in-branch, full-service investment advisory and brokerage unit in July, while LPL purchased the assets of the four National Planning Holdings IBDs in August 2017.

While smart deals have helped some IBDs thrive, the trend also cuts the number of legacy, 50-year old companies. Woodbury's parent, backed by its private equity owner Lightyear Capital, will itself be absorbing one of the seven firms founded in 1968. Advisor Group and Hancock agreed in June to a deal which would fold in some 1,800 advisors from Signator into Royal Alliance Associates upon closing in the fourth quarter.

The number of IBDs has fallen by more than a quarter over the past decade to 116 firms, according to Cerulli, which classifies IBDs separately from another group of around 750 boutique BDs.

"Consolidation pressure is real, and you do see fewer broker-dealers with a greater share of advisors and share of overall assets," says Shirk, noting the importance of tech, multi-affiliation structures and support for planning in an era of margin and regulatory pressure. "All of those competitive factors really require a firm to have scale to deliver on them in any breadth or depth."

Dizzying changes

The paths of these 50-year-old firms display the extent of the industry's turnover, although most stayed with the same parent over that time. Lincoln, which has about 1,100 advisors and $309.7 million in annual revenue, acquired fellow IBDs Capital Analysts in 2012 and Legend Group last year.

Forst says it has merged the firms under one umbrella on the brokerage side but is working to place them under the same RIA in future years. The firm's middle-class base is broadening to include HNW clients, though Forst sees regulation, tech and data security as challenges facing all financial services.

"Our biggest challenge is not so quantifiable as those three things. It's really growing in order to stay competitive," Forst says. "We can compete with anyone but be small enough that all voices can be heard."

In Iowa, Bankers Life changed the name of its IBD to Princor Financial Services in 1986, a year after the parent firm became Principal Financial Group. Two years ago, the IBD turned into Principal Securities, which has nearly 1,600 producing reps and $300 million in revenue as the No. 22 firm in the space.

Allowing career agents to sell the firm's mutual funds served as "the driving force" for its founding, says Mike Beer, who was president of Princor from 2005 to 2015 and now serves as the executive director of Principal Funds.

The firm "has eventually evolved as a broker-dealer serving a full range of proprietary and nonproprietary investment products and has also added RIA services for agents and advisors who want to operate on a fee-basis versus commission-based," Beer says.

While its name has remained the same all this time, Onesco followed a similar path to becoming the No. 49 IBD with 650 advisors and $62.8 million in revenue last year. Its parent, Ohio National, made a major change in September by ceasing any new annuities or retirement plans to focus on life and disability insurance and grow its Latin American business. It remains to be seen how the pivot will affect the IBD.

Advisor-directed programs came into Onesco's corporate RIA around 2011; the firm had earlier expanded from annuities to mutual funds and a full-service brokerage platform by the mid-'90s, says Jay Bley, the firm's vice president of national sales.

"In the past, the majority of our efforts focused on improving how we processed transactions," Bley says. "Now they are focused on practice management in areas such as transitioning to a fee-based model, effectively deploying technology to enhance the client experience and developing an effective succession plan."

Threats and opportunities

Will the Class of '68 survive another 50 years? Already, one will disappear from the list in 2019, when Signator is absorbed into Royal Alliance Associates.

Now, RIAs - a sector that sprang up in the '80s and '90s and became intertwined with IBDs - are the main challenge, according to Shirk of Cerulli.

To stem "the risk of losing their largest and most productive advisors to the RIA channel," the firms must provide advisors with an "integrated comprehensive offering" to show the value of centralized support, he says.

The firms must also boost their technology to address the expectations of clients in the era of Amazon and shift to serving a much more diverse base of clients, according to FSI's Brown. A growing need for the firms' services is "a great problem to have" going forward, he says.

"The vast majority of investors need professional advice in order to sort through the myriad options and make sound financial decisions," he says. "The demand for advice, the need for advice is greater than ever. And therefore the business opportunity of providing advice is practically unlimited."

Leffler, Warren K., photographer, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress,LC-U9-19759- 4/4A [P&P]