Want unlimited access to top ideas and insights?

Since it was signed into law in March, advisors have pored over the CARES Act's many provisions. Contained below are the most notable provisions relevant to financial planners and their clients.

Perhaps no single provision in the CARES Act received more interest than Section 2201, Recovery Rebates for Individuals. In short, people wanted to know whether they should be expecting a check from Uncle Sam, and if so, how much the check would be for.

The good news is that more than 90% of taxpayers were slated to receive some amount of recovery rebate, according to estimates by the Tax Foundation. The bad news is that, thanks to the way the law was drafted, there are likely a substantial number of people who could really use the help right now who won’t qualify for such payments because of high prior-year income.

Calculating a taxpayer’s recovery rebate advance

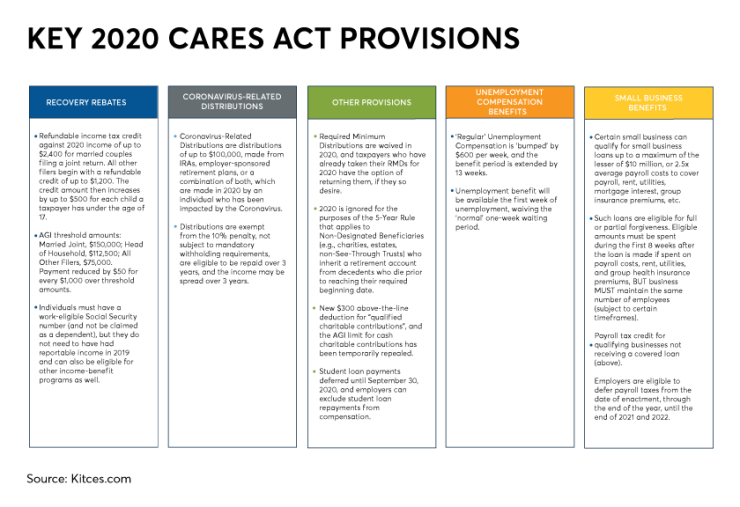

As a starting point, the CARES Act provides a refundable income tax credit against 2020 income of up to $2,400 (more on this in a bit) for married couples filing a joint return, while all other filers begin with a refundable credit of up to $1,200. The credit amount is increased by up to $500 for each child a taxpayer has under the age of 17.

Thus, a single taxpayer with one child would be eligible for up to a $1,200 + $500 = $1,700 refundable credit, while a single taxpayer with two young children would be eligible for up to a $1,200 +$500 + $500 = $2,200 credit. A married couple, on the other hand, with one child and who file a joint return, would be eligible for up to a $2,400 + $500 = $2,900 credit, while the same couple with four children would be eligible for up to a $2,400 + $500 + $500 + $500 + $500 = $4,400 credit.

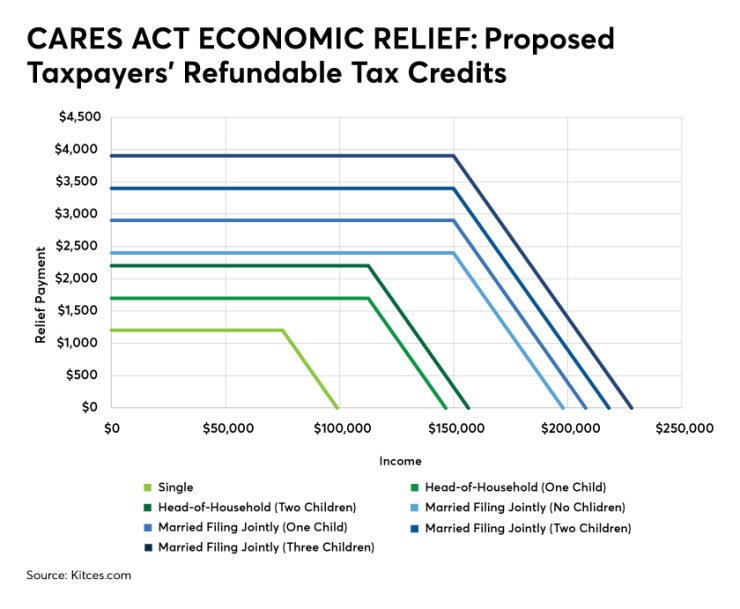

If you’ve read the last two paragraphs closely, you probably noticed a lot of “up to”s in there. There’s a reason for that. As a taxpayer’s income begins to exceed their applicable threshold, their potential recovery rebate payment (their credit) begins to phase out. More specifically, for every $100 a taxpayer’s income exceeds their credit, their potential recovery rebate will be reduced by $5.

The applicable AGI threshold amounts are as follows:

Married joint: $150,000

Head of household: $112,500

All other filers: $75,000

Example #1: Mickey and Jackie are married and file a joint return. They have four children, ages 10, 13, 15, and 17, and have $176,000 of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI).

As such, they are eligible to receive a maximum recovery rebate of $2,400 + $500 + $500 + $500 = $3,900! (Note: Recall that the potential recovery rebate is only increased by $500 for each child under 17, so only three of the couple’s children qualify.

But while $3,900 is the maximum potential recovery rebate the couple to which the couple could be entitled, they have income in excess of their $150,000 threshold amount. More specifically, they are $26,000 over their threshold amount, so their recovery rebate must be reduced by $26,000 x 5% = $1,300.

As such, the ultimate recovery rebate check that Mickey and Jackie will receive will be $3,900 – $1,300 = $2,600!

Notably, two taxpayers who have the same filing status will have different phaseout ranges if they have a different number of qualifying children. Because while a taxpayer’s recovery credit will begin to phase out after income exceeds a threshold determined by filing status alone, the starting (potential) recovery credit ‘burn rate’ is a constant $5 per $100 of additional income. Thus, as can be seen in the graph below, the greater the number of qualifying children a taxpayer has, the wider their phaseout range.

Recovery rebate split personality

One of the more confusing aspects of the recovery rebate is that it has a bit of a split personality. The initial amount paid is based on either a taxpayer’s 2018 or 2019 income tax return (whichever is the latest return that the IRS has on file), while it will ultimately be trued up if a taxpayer is owed money based on their actual 2020 income.

In other words, Congress is going to front taxpayers an estimated amount based on their 2018/2019 incomes, but if the 2020 return shows they really deserved it, they’ll get it after all, albeit much later. This little wrinkle may cause any number of headaches.

Perhaps the individuals most negatively impacted those who had high income in 2018/2019, but who have since been laid off, furloughed or had their incomes substantially decrease for other reasons. In such situations, individuals may have a genuine need for income at this very moment. And while they will ultimately benefit from the recovery rebate in April of 2021 (or whenever they file their 2020 return), that is of absolutely no use to them today.

Example #2: Georgia is a single taxpayer with no children who made $150,000 as a boutique travel agent in 2019, the most recent year for which a tax return is on file with the IRS. Unfortunately, in early February of 2020, after making just $8,000 for the year, she was let go and has been unable to find new employment.

Suppose that Georgia is not re-employed until July, and ultimately makes ‘just’ $45,000 in 2020. Given these set of facts, Georgia is actually eligible for a $1,200 Recovery Rebate, because her income is well below the $75,000 threshold amount for single filers.

However, because Georgia’s 2019 income was $150,000, she won’t get any cash flow assistance now via a Recovery Rebate check (or direct deposit) but, rather, will have to wait until her 2020 income tax return is filed to have it applied.

Now I ask you… How does that possibly help Georgia now, when she is at the greatest need? (Hint: It doesn’t.) And given the fact that more than 20 million people filed for unemployment in April 2020 alone, it’s likely that there are a lot of ‘Georgia’s’ out there!

Of course, while many taxpayers are likely to see income decreases in 2020 as compared to previous years, some will surely see their incomes rise. And for some, that might mean that they get a check now that they don’t really ‘deserve’ based on their ultimate 2020 income.

Perhaps surprisingly, there will be no clawback when they file their 2020 return. Such (lucky) individuals get to keep their recovery rebate.

Example #3: Sunny is a toilet paper distributor who files a joint return and has four children under the age of 10. Therefore, he has a potential Recovery Rebate of $4,400.

In 2019, the most recent year for which a return is on file with the IRS, he and his wife had AGI of $130,000, well below their threshold amount of $150,000. As such, the IRS will send Sunny a check for $4,400, his maximum potential rebate amount.

Suppose, though, that due to a large increase in the demand for toilet paper in 2020, Sunny has his best year ever, and he and his wife have $240,000 of AGI. Despite the fact that they are well above the income phaseout range, they get to keep the $4,400 Recovery Rebate, further enhancing what is, at least from an income perspective, already an excellent year for the couple.

And, of course, income is far from the only thing that may change over time. For example, there were about 3.8 million children born in 2019 that won’t show up on a 2018 return, but for whom parents may be entitled to a $500 rebate. Marriages and divorces have occurred, and people have died.

All of these may result in payments (or lack thereof) that are being received now ending up being dramatically different than the rebate an individual is entitled to based on their 2020 facts and circumstances, and that won’t be sorted out until the 2020 return is filed.

Coronavirus-related distributions

Mirroring similar relief that has been provided to individuals in federally declared disaster areas (hurricanes, wildfires and floods, for example), the CARES Act creates coronavirus-related distributions. These are distributions of up to $100,000, made from IRAs, employer-sponsored retirement plans, or a combination both, which are made in 2020 by an individual who has been impacted by the coronavirus because they:

- Have been diagnosed with COVID-19;

- Have a spouse or dependent who has been diagnosed with COVID-19;

- Experience adverse financial consequences as a result of being quarantined, furloughed, being laid off, or having work hours reduced because of the disease;

- Are unable to work because they lack childcare as a result of the disease;

- Own a business that has closed or operate under reduced hours because of the disease; or

- Meet some other reason that the IRS decides to say is OK.

Given the laundry list of potential individuals who may qualify for relief under this provision, it seems rather clear that Congressional intent was to make this provision broadly available. The IRS will likely operate in kind, and take a liberal view of who has been impacted by the coronavirus enough to qualify for a distribution.

There are a number of potential tax benefits associated with the coronavirus-related distributions. More specifically, these include:

- Exempt from the 10% penalty – Individuals under the age of 59 ½ may access retirement funds without the normal penalty that would otherwise apply.

- Not subject to mandatory withholding requirements – Typically, eligible rollover distributions from employer-sponsored retirement plans are subject to mandatory federal withholding of at least 20%. Coronavirus-related distributions, however, are exempt from this requirement. Plans can rely on a participant’s self-certification that they meet the requirements when processing a distribution without mandatory withholding.

- Eligible to be repaid over 3 years – Beginning on the day after an individual receives a coronavirus-related distribution, they have up to three years to roll all or any portion of the distribution back into a retirement account. Furthermore, such repayment can be made via a single rollover, or multiple partial rollovers made during the three-year period. Finally, if distributions are rolled using this option, an amended return can (and should) be filed to claim a refund of any tax paid attributable to the rolled over amount.

- Income may be spread over 3 years – By default, the income from a distribution is split evenly over 2020, 2021, and 2022. A taxpayer can, however, elect to include all of the income in their 2020 income.

(Note: Although, in general, spreading the income of a retirement account distribution over three years is likely to result in a better tax outcome than including all the income in just a single tax year, that may not be the case now. Notably, if an individual is experiencing significant financial difficulty and, to meet expenses, they take a coronavirus-related distribution, it likely indicates lower-than-normal income, at least temporarily, for 2020. If higher income is expected in future years as life returns to some aspect of normal, it may be best to include all the income on 2020’s return. Plus, as an added bonus, if some or all of the distribution is later rolled over within the 3-year repayment window, it’s only one tax return to amend)

Employer-sponsored retirement plans

Many employer-sponsored retirement plans, such as 401(k)s and 403(b)s, offer participants the option of taking a loan of a portion of their retirement assets. For individuals who have been impacted by the coronavirus (using the same definition as outlined above for coronavirus-related distributions), the CARES Act enhances the regular plan loan rules by allowing (but not requiring) plans to relax such rules in the following three ways:

- Maximum loan amount is increased to $100,000 – The maximum amount that may be borrowed from an employer plan is $50,000. The CARES Act doubles this amount for affected individuals.

- 100% of the vested balance may be used – Once an individual has a vested plan balance that exceeds $20,000, they are only eligible to take a loan of up to 50% of that amount (up to the normal maximum of $50,000). The CARES Act amends this rule for affected individuals, allowing them to take a loan equal to their vested plan balance, dollar-for-dollar, up to the $100,000 maximum amount.

- Delay of payments – Any payments that would otherwise be owed on the plan loan from the date of enactment through the end of 2020 may be delayed for up to one year.

RMDs Are Waived In 2020

Section 2203 of the CARES Act amends IRC Section 401(a)(9) to suspend RMDs during 2020. The relief provided by this provision is broad and applies to traditional IRAs, SEP IRAs, and SIMPLE IRAs, as well as 401(k), 403(b), and governmental 457(b) plans. Furthermore, the relief applies to both retirement account owners, themselves, as well as to beneficiaries taking stretch distributions.

In one somewhat surprising twist, the CARES Act not only eliminates RMDs for 2020 but any RMD that otherwise needed to be taken in 2020. More specifically, individuals who turned 70 ½ in 2019, but did not take their first RMD in 2019 (and thus, would have normally been required to take such a distribution by April 1st, 2020, as well as a second RMD for 2020 by the end of 2020) do not have to take either their 2019 RMD or their 2020 RMD. Thus, these procrastinators get to escape two RMDs instead of just one!

However, it is worth noting that while RMDs are suspended for 2020, voluntary distributions are still allowed, including qualified charitable distributions for IRA owners and IRA beneficiaries age 70 1/2 or older. And while such a distribution would not, for 2020, offset any amount of a taxpayer’s RMD (because they don’t have one), it still allows an individual to use entirely pre-tax dollars to satisfy their charitable intent.

Returning unwanted 2020 RMDs that have already been distributed

Though the CARES Act was enacted into law prior to the end of March 2020, a number of individuals had already taken their RMDs – or at least, what they thought was their RMD at the time – for 2020. Now, in light of the CARES Act, these individuals may wish to ‘return’ unwanted and no longer necessary RMDs.

For IRA, 401(k), and other retirement account owners, this may be possible in a variety of different ways. In a best-case scenario, the distribution will have taken place within the last 60 days, and the distribution won’t be prevented from being rolled over due to the once-per-year rollover rule (either because it came from a plan, is going to a plan, or because no IRA-to-IRA rollover has been made within the past 365 days). In such instances, an individual can simply write a check, or otherwise transfer an amount equal to the RMD back into a retirement account before the end of the 60-day rollover window.

Additionally, in April 2020, the IRS released Notice 2020-23, which extends the 60-day rollover rule for distributions taken on or after February 1, 2020 to the later of 60 days after receipt of the distribution, or July 15, 2020. Thus, only 2020 distributions taken in January are outside of their applicable rollover window.

For those retirement account owners who took their RMD very early in the year, and for whom the 60-day rollover window has already expired, there is another potential approach. If it can be shown that the individual has been impacted by the COVID-19 crisis enough to qualify under the liberal guidelines outlined earlier for a coronavirus-related distribution, then the rollover can still be completed… anytime for the next three years (from the date the distribution was received).

Notably, while most benefits in the CARES Act are only available for actions occurring either after the president declared a national emergency or, in other cases, the enactment of the law, the coronavirus-related distribution provision can apply to distributions as early as January 1, 2020.

But what about beneficiaries who took RMDs already? Is there any relief for them? Unfortunately, the answer is no. A beneficiary is not eligible to make a rollover. As such, even if the distributed RMD was made within the last 60 days, there is no way to get it back into the inherited retirement account.

(Note: The lone exception for beneficiaries would be for a spouse who chose to remain a beneficiary of the deceased spouse’s retirement account. In such an instance, they may be eligible to put the RMD back into their own retirement account, as a spousal rollover, using one of the methods described above.)

2020 is ignored for purposes of the 5-year rule

A final item addressed by the CARES Act’s suspension of RMDs for 2020 is the way it impacts the 5-year rule that applies to non-designated beneficiaries (e.g., charities, estates, non-see-through trusts) who inherit a retirement account from decedents who die prior to reaching their required beginning date.

In general, such beneficiaries must distribute the entirety of their inherited assets by the end of the fifth year after the retirement account owner’s death. The CARES Act, however, allows 2020 to be ignored, or simply not counted as one of those five years. Thus, for non-designated beneficiaries subject to the 5-year rule who inherited from a decedent dying between 2015 – 2019, the 5-year rule is effectively a 6-year rule!

(Note: Many individuals have been inquiring whether a similar extension of time applies to the new 10-year rule imposed by the SECURE Act on non-eligible designated beneficiaries. The answer is: No. Recall that 2020 is the first year that an individual could have died with and had a beneficiary subject to the 10-year rule. And that does not actually begin until the year after the year of death. Therefore, 2020 doesn’t count as 1 of the 10 years for purposes of the 10-year rule.)

Temporary deduction for qualified charitable contributions

Having recently removed many of the above the-line-deductions via the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in the interest of simplicity (at least that’s what they said), Congress promptly introduces a brand-spanking-new above-the-line deduction in the CARES Act for qualified charitable contributions made to qualifying charities.

The bad news is that the deduction, which is effective for 2020 only (as clarified by a

The good news, though, is that while the impact on an individual basis may not amount to much, a substantial number of people will be able to take advantage of this not-so-substantial benefit. That’s because, in order to claim the deduction, a taxpayer cannot itemize deductions on their federal return. But thanks to the TCJA’s near-doubling of the standard deduction, only about 10% of taxpayers today itemize deductions on their federal return… which means about 90% of taxpayers can potentially benefit from this new tax break in at least some way.

Notably, qualified charitable contributions must be made in cash. And they cannot be used to fund either donor-advised funds or 509(a)(3) “supporting organizations”.

Temporarily repealed: AGI limit for cash charitable contributions

Section 2205 of the CARES Act temporarily increases the AGI limit on cash contributions made to charities to a maximum of 100% of AGI for “qualified contributions” from a maximum of 60% of AGI (previously increased from 50% by the TCJA). As such, an individual can completely wipe out their 2020 tax liability with charitable contributions. If total charitable contributions exceed the 2020 100%-of-AGI limit (so, effectively, once a taxpayer has brought their 2020 income tax liability to $0), the excess may be carried forward as a charitable contribution for up to five years.

Notably, though, this provision expressly prohibits such contributions from funding either DAFs or 509(a)(3) “supporting organizations”.

Relief for student loan borrowers

The CARES Act includes several provisions aimed at providing relief to student loan borrowers, including the following:

- Student loan payments deferred until September 30, 2020 – Section 3513 suspends required payments on federal student loans through September 30, 2020. During this time, no interest will accrue on this debt. Unfortunately, though, while required payments are suspended, voluntary payments are not prohibited. And by default, payments will continue unless individuals take proactive measures to contact their loan provider and pause payments.

Also notable is that this period of time will continue to count towards any loan forgiveness programs. As such, any student borrower who intends to qualify for a program that will ultimately forgive the entirety of their federal student debt (such as via the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program) should immediately pause payments. Because whereas other borrowers who continue to pay federal student loans during this time may simply be paying down what is effectively 0% debt (at least temporarily), those borrowers who will ultimately have their outstanding student debt forgiven (upon completion of whatever requirements are necessary for their particular loan forgiveness program) are paying down a debt that would otherwise be wiped clean anyway!

Finally, all involuntary debt collections are also suspended through September 30, 2020. This not only includes wage garnishment or the reduction of other federal benefits but the reduction of any tax refund (for student loan purposes). As such, borrowers of student debt who are delinquent on payments and would normally be subject to a reduction of their tax refund have an incentive to file their tax returns early enough so that the refund is processed before this relief expires.

- Employers can exclude student loan repayments from compensation – Section 2206 provides employers a (very) limited window of time in which they can take advantage of a special rule to aid employees paying down student debt. In general, amounts paid by an employer to an employee which are used to pay student debt (or payments made by an employer directly to the loan provider) are considered compensation to the employee and are subject to income tax.

Under Section 2206, however, employers have from the date of enactment of the law, through the end of the year, to provide employees with up to $5,250 for purposes of student debt payments and exclude those amounts from their income. This amount, however, is coordinated with the ‘regular’ $5,250 limit that employers can provide employees tax-free for current education. As such, the total maximum tax-free education assistance an employer can provide an employee in 2020 is $5,250.

- Pell Grant and subsidized federal loan relief for students leaving school – Both Pell Grants and subsidized federal student loans are subject to various limits. Section 3506 of the CARES Act excludes from a student’s period of enrollment any semester that a student does not complete due to a qualifying emergency. Section 3507 does the same with respect to the federal Pell Grant duration limit.

Curiously, both provisions are contingent upon the secretary of education being “able to administer such policy in a manner that limits complexity and the burden on the student.”

Finally, if a student withdraws from school during the middle of a semester (or equivalent) because of qualifying emergency, Section 3508(b) eliminates the amount of a student’s Pell Grant that would normally have to be returned, while 3508(c) cancels any direct loan that was taken to pay for the semester.

Definition of qualified medical expenses is expanded

Per Section 3702 of the CARES Act, beginning in 2020, the definition of qualified medical expenses, for purposes of health savings accounts, Archer medical savings accounts and healthcare flexible spending accounts is expanded to include over-the-counter medications.

Qualified medical expenses for such accounts are further expanded to include amounts paid for menstrual care products.

Select provisions for individual healthcare

It should come as no surprise that the CARES Act is absolutely loaded with health-related provisions (it is, of course, being passed in response to what is likely the single greatest health-related event of most Americans’ lives). With that in mind, other notable personal healthcare provisions include the following:

- Medicare beneficiaries will be eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine (when available) at no cost (Section 3713);

- During the COVID-19 emergency period, Medicare Part D recipients must be given the ability to have, upon request, up to a 90-day supply of medication prescribed and filled (Section 3714);

- Telehealth services may be temporarily covered (through plan years beginning in 2020) by an HSA-Eligible HDHP before a participant has met their deductible (Section 3701); and

- Rules for providing Telehealth services are relaxed during the COVID-19 emergency period for Medicare (Section 3703), federally qualified health centers and rural health clinics (Section 3704), home dialysis (Section 3705), and hospice care recertification (Section 3706).

Cornucopia of additional unemployment benefits

For many who have already lost their jobs, and for the countless more who may still find themselves subject to the same fate in the coming weeks, there is, thankfully, some (relatively) good news. Unemployment compensation benefits have been significantly expanded by the CARES Act. These enhancements include:

- Pandemic unemployment assistance – Self-employed individuals (who are generally ineligible for unemployment compensation benefits), and other individuals who are ineligible for regular unemployment, extended unemployment or pandemic unemployment insurance, or run out of such insurance, will be eligible for up to 39 weeks of benefits via this provision.

- Uncle Sam will cover unemployment for the first week – In general, individuals are ineligible to receive unemployment benefits the first week that they are unemployed. It essentially amounts to an elimination period that’s meant to encourage people to try and get another job quickly so as to avoid the week without income. Of course, at the present time, finding work quickly will be difficult, if not impossible. In recognition, the CARES Act offers to pay states to provide unemployment compensation benefits immediately, without the one-week waiting period.

- Unemployment compensation is bumped by $600 per week – Section 2104 of the CARES Act provides states with the ability to increase their unemployment benefits by up to $600 per week with federally-funded dollars, for up to four months. This has the ability to dramatically increase the amount of money an individual is entitled to temporarily receive via unemployment compensation benefits, as the average weekly unemployment benefit nationwide is under $400. Thus, many individuals will see their unemployment checks increase by 150% or more, thanks to this part of the CARES Act.

- Unemployment compensation is extended by 13 weeks– In the event that people are nearing – and ultimately reach – the maximum amount of weeks of unemployment compensation provided under state law, Section 2107 of the CARES Act will allow them to receive such benefits for an additional quarter.

- Incentives to create short-time compensation programs – Section 2108 of the CARES Act provides an incentive for states who do not currently have “short-time compensation” programs to establish such programs by covering 50% of the establishment costs incurred through the end of the year. Short-time programs are meant to help those employees who have seen hours cut (or similar cuts) and have had income drop, but who are still employed, and therefore, ineligible for unemployment compensation benefits.

Paycheck Protection Program and forgivable loans

Another significant potential benefit included in the CARES Act for business owners is the Paycheck Protection Program offered through the Small Business Administration. Such loans – which were so popular after the CARES Act was initially passed that the program ran out of funds, only to be refilled by Congress via subsequent legislation in April 2020 – must be applied for by June 30, 2020, and can have a maturity of two years. They are being provided via existing approved SBA lenders, as well as lenders who are otherwise certified by the SBA to offer such loans. Furthermore, such loans are 100% guaranteed by the SBA.

Qualifying for the PPP

Businesses, including sole proprietorships, that have fewer than 500 employees (including affiliated businesses), or the employee size standard under NAICS Code, if larger, are eligible for this relief (food service businesses also apply if they employ fewer than 500 people per physical location). Eligible borrowers are also required to make a good-faith certification that the loan is necessary due to the uncertainty of current economic conditions caused by COVID-19 (though under a recent safe harbor announced by the U.S. Treasury via FAQs, the certification for any loan equal to or less than $2 million will be deemed valid).

Under the PPP, lenders will generally be able to issue SBA 7(a) small business loans up to a maximum of the lesser of $10 million, or 2.5 times the average monthly payroll costs over the previous year (excluding annual compensation of amounts over $100,000 per person), plus the amount of certain refinanced economic injury disaster loans. And the proceeds of such loans may be used to pay a variety of costs, including:

- Payroll costs

- Group health insurance premiums and other healthcare costs

- Salaries and/or commissions

- Rent

- Mortgage interest (excluding amounts pre-paid)

- Utilities

- Other business interest incurred prior to February 15, 2020

Benefits of PPP loans

The single largest potential benefit of a loan issued under the PPP is the possibility of having all or a portion of the loan forgiven. The amount eligible to be forgiven is the amount spent, during the first 8 weeks after the loan is made, on:

- Payroll costs, excluding prorated amounts for individuals with compensation greater than $100,000;

- Rent pursuant to a lease in force before February 15, 2020;

- Electricity, gas, water, transportation, telephone, or internet access expenses for services which began before February 15, 2020; and

- Group health insurance premiums and other healthcare costs.

If this sounds too good to be true, it won’t surprise you to learn that there is a catch. For the above amounts to be forgiven, the business must maintain the same number of employees (equivalents) in the eight weeks following the date of origination of the loan as it did during other specified periods (generally from either February 15, 2019 through June 30, 2019, or from January 1, 2020 through February 29, 2020 (but different dates may apply to certain seasonal businesses). To the extent this requirement is not met, the amount eligible for forgiveness will be reduced, ratably. Additional reductions in the amount to be forgiven will be incurred if employees with under $100,000 of compensation have their compensation cut by more than 25% as compared to the most recent quarter.

And as if this benefit weren’t good enough, it actually gets even better! Any debt forgiven pursuant to this provision is not included in taxable income for the year.

Second, the interest rate for a loan made under this program is 1%. Small businesses tend to be risky borrowers, so the ability to borrow up to roughly $10 million at 1%, and over a term of up to 2 years, is a pretty significant win for many small businesses in and of itself.

Finally, payments for loans made under the Paycheck Protection Program will be deferred for a period of six months.

New employee retention credit

As an incentive to encourage businesses who have been hit hard by the economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis from making further layoffs, Section 2301 of the CARES Act introduces a new payroll tax credit (provided they are not receiving a covered loan under section 7(a)(36) of the Small Business Act).

Qualifying for the employee retention credit

The trigger for a company to begin to be eligible is that its operations have been fully or partially suspended during a quarter either as a result of a governmental authority or in which revenue in 2020 has less than 50% of the revenue from the same quarter in 2019.

As such, a business which is not at least partially suspended because of government restriction, and which never sees its year-over-year quarterly revenues plummet below the 50% mark, will not be eligible for the credit.

For those businesses that do meet this (unfortunate) requirement, the business will continue to qualify for the credit until the earlier of:

- The end of 2020; or

- Depending upon the method of qualification for the credit, there is either a quarter without a government-required suspension of operations, or the quarter following the quarter in which gross revenue from the current quarter exceeds 80% gross revenue from the same calendar quarter in 2019, whichever is sooner.

Notably, for businesses qualifying for the credit based on revenue, by virtue of the fact that at least one quarter’s revenue in 2020 must be more than 50% less than the revenue for the same quarter in 2019, a company experiencing a sustained substantial (but not-substantial-enough) decrease in revenue throughout the year, may never qualify for the credit.

Meanwhile, a company that experiences a more temporary, but dramatic decline in revenue, and which actually experiences a much better year overall, may, in fact, qualify for the credit in one or more quarters!

Finally, it’s worth highlighting that the key metric used here is revenue, not profit. Thus, a business with a small profit margin, such as a grocery store (which tend to have margins of less than 5%) that loses just 10% or 15% or revenue may, in fact, already be running at a substantial loss without cutting other costs.

Calculating the employee retention credit

For business planning purposes, it is important for employers not only to understand that they are eligible for a credit but also to know how much of a credit they are eligible for, as this will help inform business decisions. In the simplest terms, the credit is equal to 50% of wages paid to each employee, up to a maximum of $10,000 of wages per employee. There are, however, as usual, some important caveats to which business owners must be made aware.

Specifically, businesses with 100 or fewer employees count wages very differently from larger businesses. For small businesses (100 or fewer employees), all wages (up to the $10,000 maximum limit per employee) are eligible to count towards the credit. By contrast, for larger employers with more than 100 employees, only wages paid to individuals (up to the $10,000 maximum limit per employee) who are not providing services (not working) during a government shutdown, or because business revenues have declined as outlined above, are eligible to count towards the credit. In both cases, wages include qualified health care expenses allocable to those wages.

Deferral of payroll tax payment

Section 2302 of the CARES Act provides employers with another payroll-related tax break. With the exception of employers who have debt forgiven by the CARES Act for certain loans provided by the SBA, employers are eligible to defer payroll taxes from the date of enactment, through the end of the year, until the end of 2021 and 2022.

More specifically, 50% of the payroll taxes that would otherwise be due during this period may be deferred until December 31, 2021. The remaining 50% is due on December 31, 2022.

The good news for self-employed persons is that this relief applies to them too, at least with respect to the ‘employer equivalent’ portion of their self-employment taxes. Accordingly, 50% of an individual’s self-employment taxes, from the date of enactment through the end of 2020, may be deferred, with 50% of that amount (so 25% of 2020 self-employment taxes) due December 31, 2021, and the remaining deferred amount due on December 31, 2022.

Notably, payroll taxes and self-employment taxes fund programs such as Medicare and Social Security, which are significantly underfunded already. To mitigate further impact to these programs, the CARES Act authorizes Congress to appropriate amounts from elsewhere in an amount equal to the deferred amounts that would have otherwise gone into the trust funds. And interestingly, there doesn’t appear to be an offset when those deferred payments ultimately do go into the trust funds.

So, perhaps Social Security and Medicare actually get a little boost thanks to the CARES Act (which, admittedly, would probably just offset some of the effects of reduced payrolls in 2020)?

Net operating loss rules are loosened

Section 2303 of the CARES Act amends the rules for corporations (other than REITs) with net operating losses (NOLs). For many years, NOLs were allowed to be carried back up to two years and forward up to 20 years. The Trump tax law changes altered those rules, however, beginning in 2018, to allow such losses only to be carried forward, indefinitely.

Now, the CARES Act adjusts those rules once more, allowing any NOL from 2018, 2019, or 2020 to be carried back up to five years. In theory, this should allow companies to reduce prior years’ tax bills, allowing them to claim refunds of amounts previously paid to provide further liquidity to get them through the COVID-19 crisis.

The CARES Act further enhances the ability of companies to use their NOLs to offset prior years’ tax liabilities by amending another rule put in place by the Tax Cut and Jobs Act. Under the TCJA, NOLs were only able to offset up to 80% of taxable income. Section 2303 of the CARES Act amends the law to allow for up to 100% of taxable income to be offset for 2018, 2019, and 2020.

Section 2023 also provides relief to non-corporations as well by temporarily repealing TCJA-created IRC Section 461(l), which limits the cumulative losses that a taxpayer may claim attributable to businesses (above the income attributable to those businesses) to no more than an inflation-adjusted $250,000 for single filers, and $500,000 for joint filers. These limits are repealed for 2018, 2019, and 2020. Accordingly, taxpayers who had losses suspended because of this provision in 2018 or 2019 should consider the potential benefits of filing an amended return.

Jeffrey Levine, CPA/PFS, CFP, MSA, a Financial Planning contributing writer, is the lead financial planning nerd at