Although it is commonplace for investors to hold multiple investments in a portfolio -- often comprising mutual funds or ETFs that in turn hold dozens or even hundreds of underlying positions -- even multi-asset-class portfolios aren’t always really diversified.

Holding many different investments aligned to the same base case market scenario and that all go up or down together may be equally risky.

For instance, a so-called well-diversified portfolio holding stocks from the U.S. and emerging markets, plus commodities and corporate bonds, may be invested into multiple asset classes but would all be expected to go up in a growth environment. Conversely, they all would likely decline severely during a recession.

Of course, investments that don’t go down in a recession, from defensive stocks to government bonds, are also the investments likely to perform the worst when markets rise. But in the end, that is the whole point of diversification: to own investments that will defend in the risky events, even if it means sacrificing some upside.

Viewed another way, being well diversified means always having to say you are sorry about some investment that isn’t moving in the same direction as the rest.

Given the complexity of the investment environment and the typical multi-asset-class portfolio, a growing range of tools are becoming available to stress-test various risky scenarios, to help determine whether a portfolio is truly diversified, or just holds a large number of investments that are all expected to go up -- and down -- in an undiversified manner.

ORIGINS OF PORTFOLIO DIVERSIFICATION

The concept of diversification traces back thousands of years.

In Judaism, the Talmud illustrates the principle by stating, “it is advisable for one that he shall divide his money in three parts, one of which he shall invest in real estate, one of which in business and the third part to remain always in his hands” (

The Bible, meanwhile, recognizes the importance of diversification even more directly: “But divide your investments amongst many places, for you do not know what risks might lie ahead.” (

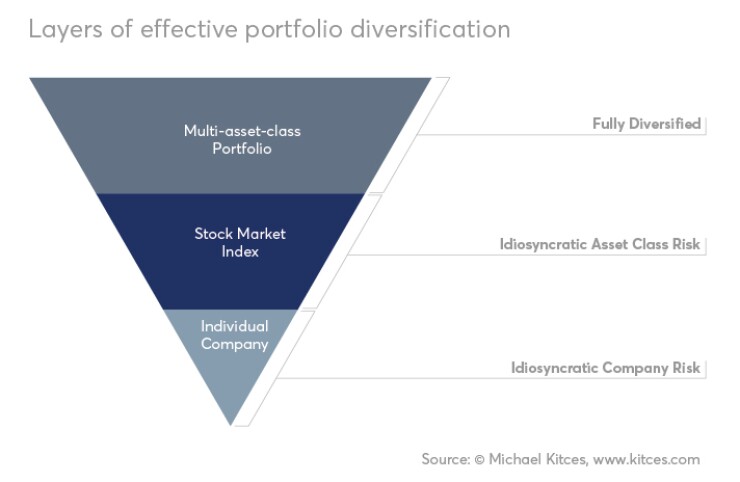

In a modern context, the Bible’s unknown risks are further divided into two subcategories: idiosyncratic risk that is specific to a particular investment (also known as unsystematic risk), and market risk that an investor takes on simply by investing in the markets (also known as systematic risk).

The distinction is important because research has shown that

Of course, it is still possible to diversify out of the stock market, which was what the Talmud prescribed by indicating that only one-third of assets should be invested into businesses, with another third in real estate -- an entirely different asset class -- and the last third “in [your client’s] hands,” e.g., in cash. More generally, this means that the next layer of diversification is to spread assets across entire asset classes, ideally ones that are so different from each other that the idiosyncratic risks of one asset class in the aggregate are still not shared by the others.

In other words, broader and broader diversification is simply about spreading investments out to minimize exposure to any one of a broader and broader range of potential risks.

DIVERSIFICATION MEANS ALWAYS HAVING TO SAY YOU ARE SORRY

The point of diversification is to spread out a client’s exposure to various risks, such that if the risky event occurs, not all investments are adversely affected. But an important corollary of diversification therefore applies as well: If the risky event doesn’t occur, not all the investments will benefit.

Imagine a portfolio invested on the base case that the economy is healthy and will keep growing. Such a portfolio would have a healthy allocation to equities, along with exposure to commodities and would likely tilt toward more volatile higher-beta stocks (e.g., small-capitalization and emerging-markets equities). A strong economy also tends to keep the default rate low, so an adviser would likely also favor corporate bonds over government bonds and ideally, high-yield bonds with the greatest return boost in a low-default environment.

Any interest rate sensitivity (i.e., duration) would be kept low, as a strong economy is likely to eventually face rising rates.

The fundamental problem with such a portfolio, however, is that while it is spread out across a number of different asset classes, it is very poorly diversified. The portfolio actually just owns multiple asset classes all aligned toward the same risk, benefiting as long as the economy grows and vulnerable if a recession occurs.

This story, adapted from a piece that ran on May 5, is part of a 30-30 series on ways to build a better portfolio.