Shannon Eusey first sketched out her idea for a financial planning firm when she was studying for an MBA and working at a small wealth management firm in Los Angeles. In a 25-page paper for her “Entrepreneurship and Venture Initiation” class at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management in 2001, she wrote a business plan for a wealth management company with a then-unusual focus: a fiduciary obligation to put a client’s interests first by charging fees for all manner of funds, securities and advice.

At the time, brokerages dominated the investing landscape, and financial advisors typically pocketed commissions from mutual funds and annuities that they were incentivized to sell. Eusey’s no-commission plan was downright countercultural. Her paper, titled “NEWCO,” got a B from the professor.

One year later, Eusey used her blueprint to start a company in Newport Beach, California, with her father, Garth, a Navy veteran who flew F-4 fighter jets in Vietnam and survived being shot down in the Gulf of Tonkin.

Two decades later, the firm they co-founded, Beacon Pointe Advisors,

Today, Beacon Pointe, the largest female-led independent advisory firm, with women filling nearly half its professional positions and with roughly $20 billion in assets, largely reflects Eusey’s original idea. But the recent Wall Street deal, which valued her firm at more than $1 billion, wasn’t in the original plan. Today, a transaction with private equity would be baked into the grand strategy for any registered investment advisory firm with big aims. “When we started in 2002, fee-only was unique,” Eusey, age 52, said in an interview. Today, she added, selling a chunk to private equity “is the evolution.”

In a modern-day gold rush for the wealth management’s industry’s

Private equity firms use money from pensions, endowments, family offices and high net worth investors to buy stakes in promising or undervalued businesses before selling them at a profit or taking them public. For decades, the multibillion- dollar shops have snapped up everything under the sun, including ambulance systems, medical and dental practices, hospitals,

Recording artists might be hot, but RIAs are targets of choice. Three in four of the top 20 RIAs, measured by Barron’s in 2020 according to size and quality of practice, are either partly or wholly owned by private equity firms or other financial institutions, such as banks, according to a

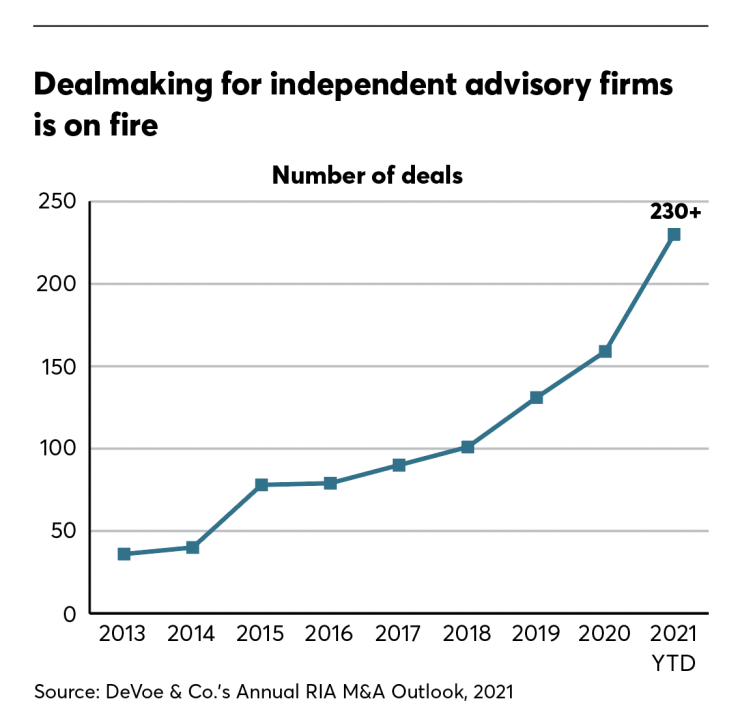

In fact, their reach into the industry is much greater than nominally appears, as the RIAs they back snap up smaller firms. So-called “consolidator” or “roll up” RIAs made 71 acquisitions of advisory firms over the first nine months of 2021, according to DeVoe. The bigger, the better, so the deal-making logic goes: More than half the deals involved firms with at least $1 billion in assets. More deals than ever being done — 230 deals over 2020 through just the first nine months, according to DeVoe, making it the eighth consecutive record-setting year for the industry — and the year in which private equity showed who’s in control.

The consolidation has only just begun. Some 700 new RIAs are started each year, according to McKinsey’s August 2021 report. As John Furey, the founder and managing partner of Advisor Growth Strategies, a wealth management consulting firm in Phoenix, told a Dec. 16 webinar hosted by the firm, “There’s still no national brand.”

The big get bigger

Leading the buying are what DeVoe calls “hyperactive acquirers” and “seasoned acquirers” — meaning PE-backed consolidators. Over 2020 and the first nine months of 2021, more than four out of five transactions came from buyers who had already bought at least one RIA. Mercer Advisors, a $36.5 billion RIA in Denver that’s majority owned by New York-based private equity firms Oak Hill Partners and Genstar Capital, has snatched up around 55 RIAs since roughly 2015. “It’s a common perception that we’re just gobbling up everything like a Hoover vacuum,” David Barton, Mercer’s M&A leader and former CEO, told the Dec. 16 webinar. “But that’s not the case.

His comment underscored how much there’s still left to buy. “It’s a red hot seller’s market,” he said during the webinar.

Never let a good crisis go to waste

RIAs appeared on private equity’s radar screen in earnest at the close of the 2008 financial crisis, when firms that had weathered the meltdown hired new advisors and began to add new clients to the ones they had shepherded through the downturn, according to a May 2020

The independent firms are overseen by the SEC, which reported nearly 13,900 firms in 2020 with nearly 61 million clients and $110 trillion in assets,

RIAs now handle around one quarter of all U.S. retail investor assets under management, or $4.7 trillion, an amount that could grow 30% in 2022,

What does Wall Street bring to the table? Cheap capital, for one thing. The cash infusion allows an RIA to go out and buy competitors. It also gives advisors a cushion in a down market and professionalized business management techniques. “We needed to grow up and mature and get beyond being this little cottage industry of businesses,” Bob Oros, the chairman and CEO of Hightower, a serial buyer, said during the Dec. 16 Advisor Growth Strategies webinar.

More wrongdoing, for another. A research

Shirl Penney, the founder, president and CEO of Dynasty Financial Partners, a St. Petersburg, Florida- based network of independent advisors, said: “It amazes me how many advisors who are frustrated sold to the first firm they met and failed to do the same level of due diligence they would recommend to their clients on a sale of all or a part of their businesses. What advisors need to understand is PE firms negotiate and transact on investments all the time; most advisors don’t.”

The paper from University of Oregon researchers posits a tension between profit motives and ethical business practices.

‘Shooting fish in a barrel’

Fiduciary-only RIAs make money through fees based on client assets. So-called “hybrid” firms, which act as fiduciaries in some situations and as broker-style non-fiduciaries in others, depending on the investment being sold, earn both fees and commissions. Either way, their profit margins average 27.5% to 33%,

“It’s much easier to get a return that’s three to four times higher than any other industry,” said Dan Seivert, the CEO and managing partner of Echelon Partners, an investment banking and consulting firm in Manhattan Beach, California. For private equity acquirers looking to make their RIAs even bigger through acquisitions, “it’s like shooting fish in a barrel.” And, like the fish, the guns are getting bigger.

Sky-high valuations

Last July, Bain Capital

As investment banks vie to broker the deals — lucrative both for them and for the sellers — is there a bubble?

In 2020, acquirers of RIAs paid on average up to eight times a firm’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, or EBITDA, a common measure of a company’s value,

That’s a 21% increase on 2019, itself a 29% rise on 2015-2018 levels. In 2019, Goldman Sachs bought RIA United Capital of Newport Beach — right where Eusey is — for $750 million. The deal valued the RIA at around 18 times EBITDA, more than double the average size of deals at the time cited by Advisor Growth Strategies.

To be sure, some high prices could reflect something other than value. Private equity firms raise money from investors, and if they don’t put that “dry powder” to use within the first five or six years, they can be forced to return it, along with the management fees they’ve collected. Amid that pressure, there’s a lot of money looking for places to go.

After two years of record M&A, rising asset prices and increasing digitization, independent advisors are poised to take on the brokerages, executives said.

“The number of buyers [of RIAs] has quadrupled over the last five years,” Barton told the webinar, adding “that alone drives up competition and pricing. Some people are willing to pay nosebleed prices.”

The gimme-the-money works both ways: Oros said that some RIAs looking to sell themselves were out only for the highest prices and the fastest deals. “We’re increasingly being asked to bid on less and less information with no access to business management” and “without the most basic details of fit,” he told the webinar.

Either way, the frenzied deal-making masks a dirty secret in the industry: relatively few individual investors actually use a financial planner. Only three in 10 consumers pay a planner,

So what is private equity actually buying? “The issue of growth is the biggest misnomer in the industry,” Barton said during the webinar. “If you exclude market growth and focus on client growth, it’s 1% to 3% net client growth,” he said, adding that most RIAs “are not adding new clients in any significant way.”

In that light, Furey thinks that acquirers may be starting to become more discerning. Deals are becoming “less size- centric,” he said at the webinar. That has more to do with the teams of people leading the firms, he said, along with “a superior 15% organic growth rate,” meaning growth that comes from snagging new clients, not from buying a competitor.

Three key letters

Beacon Pointe’s deal with KKR wasn’t its first tango with private equity. But it underscored the ambitions of Wall Street’s so-called smart money — and maybe even a bit of FOMO on both sides.

In March 2020, the RIA

Private equity typically gets rid of an investment after roughly five to seven years, not 20 months. That Abry was willing to sell so soon reflected the dizzying rate at which Beacon was growing in size and profits. It also underscored private equity’s business model of pursuing high rates of return, often upped each year, that funds set for themselves. Those benchmarks determine their ability to raise money from outside investors for new investments.

Locking in Beacon’s high internal rate of return, or IRR, after owning it for a little more than a year and a half made Abry’s decision to sell lucrative, even if the company it was offloading was increasingly profitable. “The bigger a PE firm’s portfolio company gets, the harder it is to achieve an outsized IRR,” Seivert said. “Often a PE firm will sell sooner if the prospect of holding a portfolio investment one more year will reduce the IRR, as that is the number used in the capital raising for future funds.”

DeVoe’s lookback at 2021 reveals trends and surprises.

Last April, Goldman Sachs reached out to Eusey with an idea: Sell a stake to KKR, according to a person familiar with the matter. The private equity giant, a Goldman Sachs client, was already preparing to formally exit its stake in another giant “consolidator,” New York-based Focus Financial Partners, after helping it

Barely one month later, Eusey’s firm was at it again, using her new investor’s cash to

How confident is KKR, a publicly traded company that answers to shareholders, that Beacon Pointe will get there and generate outsize profits? Very, apparently. “KKR didn’t put any IRRs on us,” Eusey said. KKR declined to comment.

Seivert called the deal “further evidence of how attractive the opportunity is in wealth management.” And, he added, of “how even though there are already more than 200 private equity firms invested in the space, KKR didn’t mind being the more-than-200th-one to the party.”