An innovative approach to mitigating significant single-stock risk could prove more effective than traditional alternatives, says the chief executive of the advisory firm that distributes it.

Called a Stock Protection Fund, the vehicle is intended to help clients in very specific circumstances, such as high net-worth executives with a majority of their wealth in company stock without the option to broadly diversify.

By combining risk-pooling and Modern Portfolio Theory, the system acts like a mutual fund in which a premium is paid to protect an asset. The SPF represents stocks held by 20 fund participants, and each stock is required to be from a different industry, diminishing the probability of all stocks hitting rock bottom at the same time.

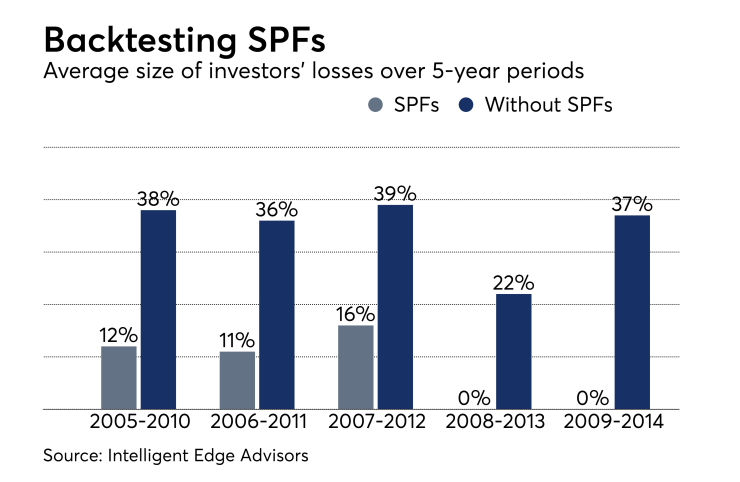

Thomas Boczar, chief executive of Intelligent Edge Advisors, a registered broker-dealer in New York that distributes the funds, says that a study of SPFs found that the risk of “catastrophic” stock losses of more than 60% was basically eliminated, and that 70% of such funds eliminated losses and returned cash to investors after the term.

Losses of more than 30% were reduced by 85%, he says.

The statistics are based on back-testing data points from 1972 to 2014.

But is the protection worth the fees?

MUTUAL INSURANCE POLICY

Adam Leone, a CFP and a principal and wealth manager at Modera Wealth Management in Westwood, New Jersey, likens this approach to a mutual homeowner insurance policy.

“You still own the stock, but if there’s a fire and your house burns down, you’ll get paid out,” says Leone, who is not affiliated with the offerings.”

To get the first fund off the ground, Boczar needs to attract 20 investors.

So far he has around a dozen, he says.

Some in the planning community are skeptical about this approach.

Dan Moisand, a CFP former president of the Financial Planning Association and principal and advisor at Moisand Fitzgerald Tamayo Wealth Management in Orlando, Florida, says that hedging long-term stocks over the near term just doesn’t make sense.

“If you believe something is a long-term core holding, you shouldn’t be concerned about short-term fluctuations,” he says. “If you are, diversifying is usually a better idea.”

HOW DO THEY WORK?

The SPFs are straightforward. Twenty investors contribute cash equal to a certain percentage of the value of their stock, usually about 5% or 10%, into a fund that is 95% invested in U.S. Treasuries with a maturity close to but not exceeding five years.

The remaining 5% is invested in a fund that holds only very short-dated Treasuries, functioning as a cash reserve.

If, after five years, investors take losses on their holdings, they are compensated with money from the bonds. Any cash left over is distributed evenly among investors.

The SPF approach was developed and patented by Brian Yolles, founder and chief executive of StockShield, a registered broker-dealer in Los Angeles that provides equity risk management services. This particular fund is a private placement sponsored by StockShield.

A handful of other firms offer such funds all through Boczar’s Intelligent Edge Advisors, the exclusive distributor.

He cites a 2006 trial of a stock protection fund that operated through the financial crisis. With 10% cash contributions protecting 20 stock positions, it returned 31% of the original contribution to investors.

Both the Dow Jones Industrial Average and S&P 500 finished moderately above their starting positions.

Nonetheless, experts such as Leone express reservations.

“Paying for that protection, year after year, is almost like death by 1,000 cuts,” he says, adding that it might make more sense to sell early, if allowed, and absorb the long-term capital gains tax, in order to diversify. “Investors may fare better just pulling off the Band-Aid.”

Yolles, however, says that the cost of the protection could be virtually zero, if all stocks gain in value, while the fees are on par with other asset management fees that investors regularly pay.

He also says that this cost is substantially lower than buying derivatives such as puts.

And, SPFs are specifically for investors who do not want to, or cannot, sell their stock, Yolles says.

“For example, many Google stockholders are ‘attached’ to their stock,” he says. “No matter what their advisor says, the client is not going to sell it.”

In addition, many stock positions are restricted or concentrated in options or stock appreciation rights that can’t be readily liquidated.

The protection doesn’t guarantee full preservation, says Anthony Roth, chief investment officer of Wilmington Trust in West Windsor, New Jersey.

According to Boczar’s study, there is an estimated 30% chance that the cash bonds won’t cover all losses.

“There are almost infinite scenarios you can imagine where you have significant unreimbursed losses,” Roth says, adding that it is a “probabilistic guess” as to whether investors are reimbursed after losses.

Additionally, stock performance can be tied to the overall market, and a deeper crisis could spell trouble for potential investors, he says.

“It’s a very imperfect downside hedge,” Roth says.

Yolles disagrees.

“Just like diversification, it is a probabilistic certainty that by participating in a SPF, your client’s risk will be substantially reduced,” he says, noting that this protection is especially important for a concentrated investor.

Unlike most traditional hedging options, this approach allows investors to maintain possession of their assets, Boczar says.

Intelligent Edge Advisors offers a $1 million SPF, and $5 million and $10 million funds are in the works.

“Traditional strategies have been to chip away at the position over time,” Boczar says, using exchange funds, also known as swap funds, or structured selling programs.

Because SPFs allow investors to retain ownership of their stock, they retain any upside appreciation, collect dividends and maintain voting rights.

There is no sale or transfer of shares, meaning that investors are also able to sell or otherwise dispose of shares through charitable gifts or bequeathments. Retaining ownership of the stock also means kicking the long-term capital gains tax down the road or avoiding it altogether through the step-up in cost basis for children or other family members.

THE FEES

The initial cash contribution is 10% of the stock’s value, which represents 2% annually over the five-year term, paid up front, along with a one-time 2% placement fee. Operational costs are covered by interest accrued from the Treasury bonds.

Leone says that he would think twice about recommending these funds to clients.

“I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s very attractive to be doing in perpetuity,” he says.

For example, if an investor thinks that a stock will produce a return over five years of 6%, each 2% annual cash contribution is a third of the anticipated gains.

However, if the investor expects the stock to grow at 10% or 20% per year, the 2% maximum potential cost would be extremely low and help offset taxable realized gains, Yolles says.

“Many concentrated stock positions could double or triple over a five-year period when including both capital appreciation and dividend income. The cost of the protection doesn’t even register in terms of the overall result for the client,” Yolles says.

NICHE CLIENTS

For clients with a known timeframe in which to sell or gift the holdings, an SPF could offer real benefits.

“If I’m moving to a tax-free state in three to five years or gifting my stock to my alma mater, then the fund becomes very interesting,” Leone says.

Moisand suggested another compelling scenario: “I can see giving it consideration in a situation of, say, a terminally ill client with a very low basis.”

Other examples are executives with huge stock value in a single company or ultrahigh-net-worth clients. Because executives are sometimes barred from selling off acquired stock positions or fear retribution from their boards after a stock dump, they may want to hold stocks and elude the long-term capital gains tax by bequeathing them to their children.

In such cases, the client may have highly appreciated single-stock holdings with no way or incentive to sell.

“Those positions are then held unhedged,” Boczar says. “There’s nothing that can be placed around them, in our current environment, that’s affordable.”

Given that an individual’s stock could appreciate, Boczar says that his clients think that the fees are well worth the price of admission.

“Two percent a year on the position, and you could still hit a homerun. That’s worth it for them,” Boczar says.

Roth disagrees, citing traditional wisdom.

“You become wealthy by being concentrated,” he says. “You stay wealthy by being diversified.”

This story is part of a 30-30 series on navigating the growing world of choices for clients. It was originally published on Oct. 5.