From sealed transcripts,

the inside saga of

LPL Financial’s largest termination ever

Former CEO Mark Casady disclosed in

arbitration testimony what led to the

firing that resulted in a $30 million

claim against the firm.

By Tobias Salinger

In 2014, when LPL Financial CEO Mark Casady learned that his friend, the broker James E. “Jeb” Bashaw, was being investigated by the firm over two separate million-dollar loans by a client as well as other irregularities, he said he was heartbroken but also felt “taken advantage of and conned.”

Casady, who’s since retired, made the comments in a FINRA arbitration hearing in August 2017. The sealed transcripts obtained by Financial Planning reveal for the first time the details of how the nation's largest independent broker-dealer turned on one of its own, moved swiftly to oust him, then had the dismissal upheld in arbitration.

“I thought it was an awful situation no matter how you look” at it, Casady said, describing Houston-based Bashaw as the largest producer ever investigated and terminated by LPL. The firm and Bashaw’s practice had expanded rapidly together for 13 years.

The Casady-Bashaw relationship went beyond business. The men went whale-watching off Cape Cod and enjoyed talking about books, such as one on Abraham Lincoln that Bashaw was reading at the time and a book on the Cape Cod Baseball League that Casady later sent him.

Casady and his wife Julia had donated money for research into Huntington's disease, an incurable genetic brain disorder that left Bashaw’s wife Kim unable to perform daily tasks at the time of his September 2014 firing. She died about six months later.

Within a month of vacationing at Casady’s Cape Cod home, Bashaw was told on a phone call with a member of LPL’s compliance and supervision staff that he had been terminated. The case presents a cautionary tale for advisors on how a loan from a client can tear apart a multimillion-dollar business.

Bashaw, 55, later named Casady in his arbitration claim, in which he sought damages of $30 million. After the panel rejected his claims last fall, in a 2-1 decision, Bashaw filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

Bashaw’s lawyers had filed unedited transcripts as exhibits in their opposition to LPL’s court filing seeking confirmation of the arbitration decision. Last November, LPL’s legal team sought successfully in Houston federal court to seal the arbitration transcripts, asserting they revealed confidential partnership information; heavily redacted transcripts were subsequently made public.

Financial Planning obtained the transcripts before they were sealed, revealing the often-hostile and dramatic exchanges. Since none of the parties involved will discuss them, they present the only details available about the case. (See excerpts from another LPL executive's testimony below.)

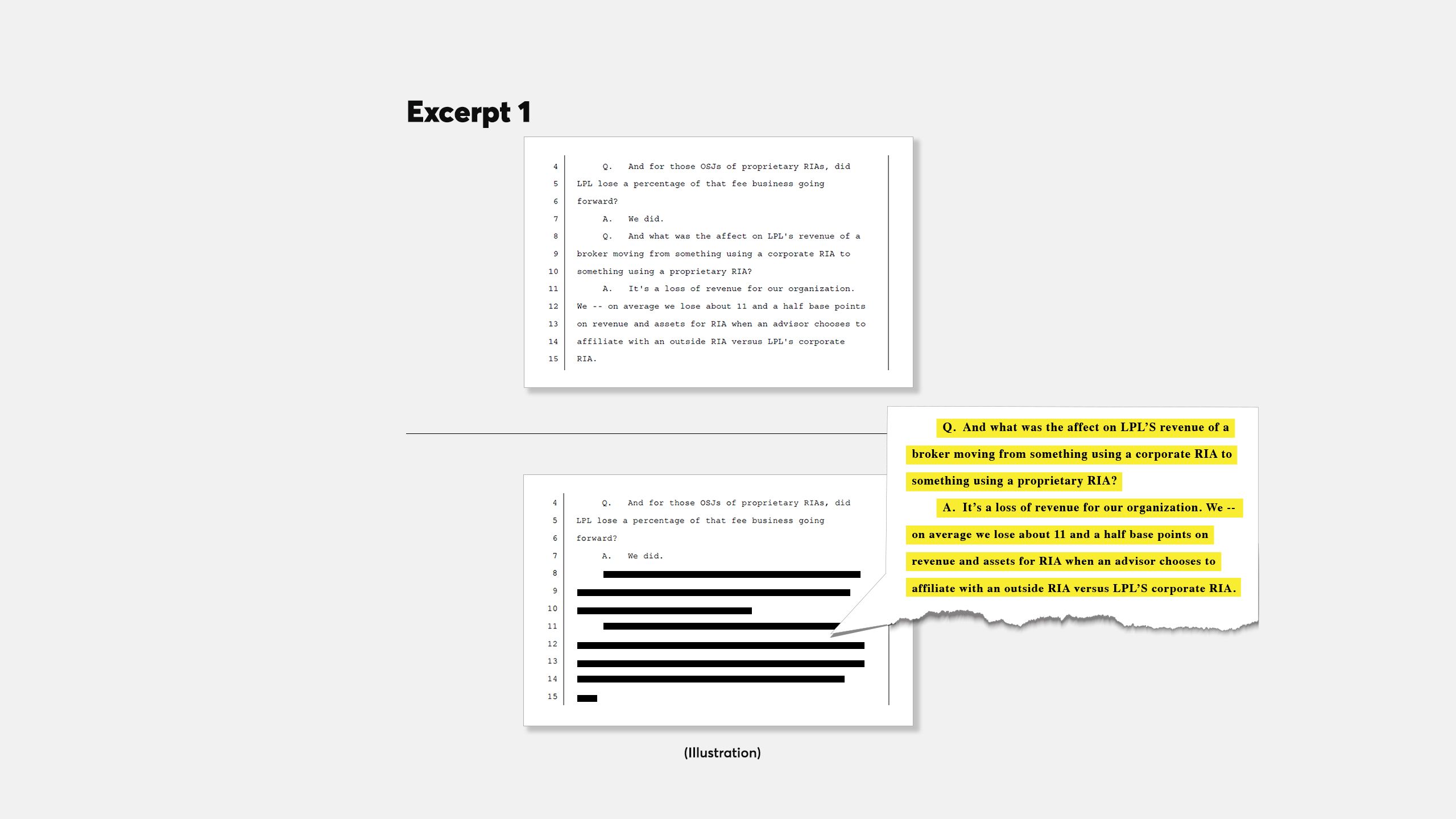

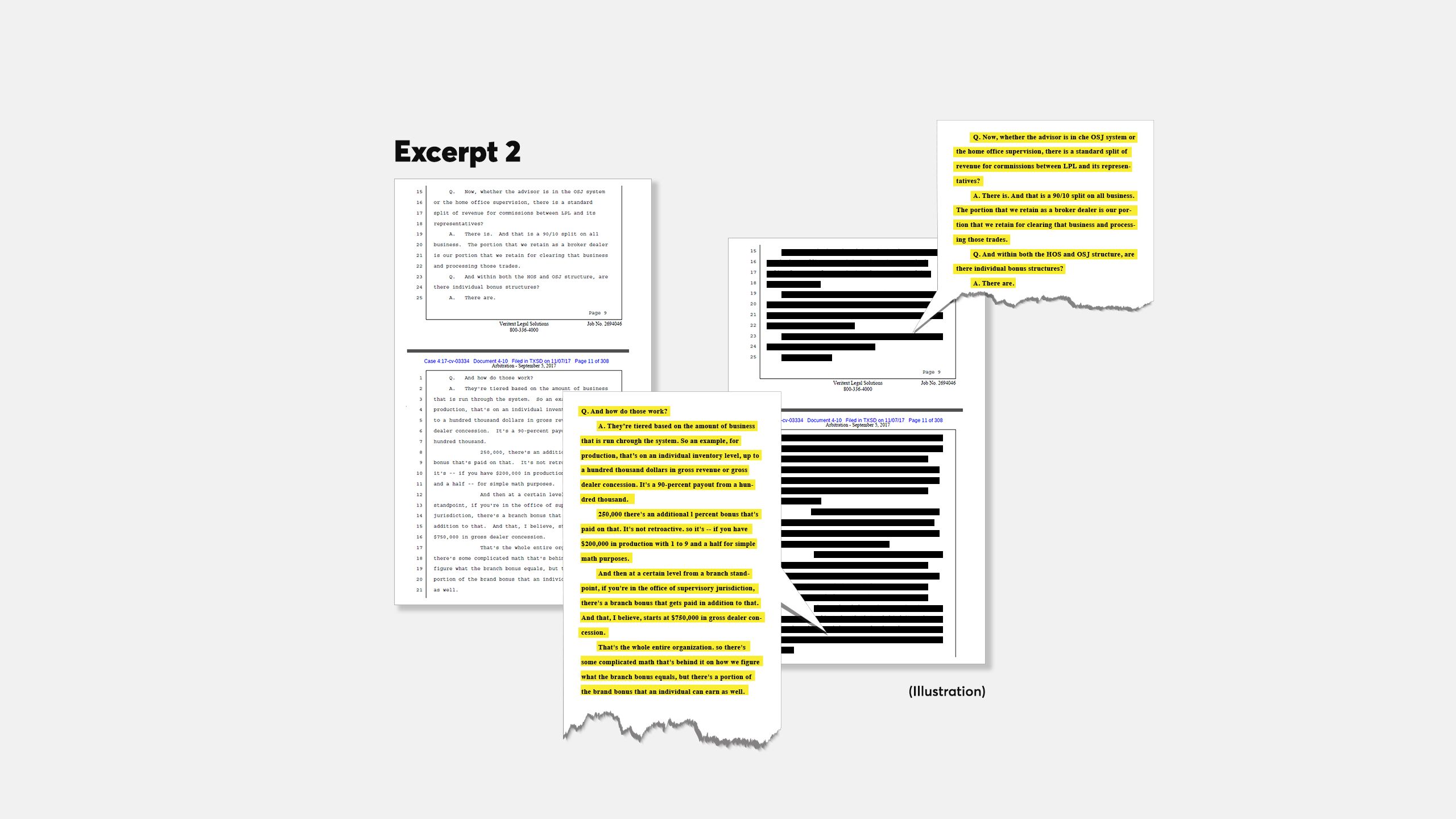

Jason Gallagher, a regional vice president for enterprise management in LPL’s business consulting unit, explained the details of LPL’s structure and financial relationships with its advisors in his testimony on Sept. 5.

(To view Excerpt 1 in higher resolution,

click here.)

(To view Excerpt 2 in higher resolution,

click here.)

‘SOMETHING BIGGER INVOLVED’

Casady attended all 13 days of hearings in Houston, according to the transcripts. That, in itself, seemed unusual. Most executives bolt FINRA arbitration sessions as quickly as possible, says Thomas Lewis, an attorney with Stevens & Lee who represents brokers and firms in arbitration but was not involved in this case.

“To sit through days of proceedings for something like this, it seems to me that there was probably something bigger involved,” Lewis says. “I have to think there’s more to it than intellectual curiosity if you’re going to sit there for several days.”

Was Casady determined to listen to every word Bashaw spoke, to observe his every gesture and study his body language? Was he monitoring every challenge to his firm’s integrity? None of the parties involved will say.

In signs of how seriously LPL took the internal investigation that led to Bashaw’s dismissal, executives accessed the bank account records of one Bashaw client using financial institutions’ authority to do so under the Patriot Act and later set up what they called a “command center” in a hotel room.

Ultimately, LPL dismissed Bashaw over two $1 million loans a client made to Bashaw’s planning practice, as well as conduct that its investigators deemed improper private securities transactions. In response, Bashaw’s lawyer accused LPL of offering him up to regulators and the news media to escape blame for failing to properly supervise Bashaw and others, and for its record of compliance troubles.

LPL, like many companies, had “growing pains,” says Lewis. But Bashaw should have known the loans would pose problems, he adds. “This is a pretty basic issue of borrowing from a client, which financial advisors know they’re not supposed to do.”

An LPL spokesman, Jeff Mochal, declined to make available for interviews any executives who testified at the hearing. “LPL is pleased with the decision of the independent arbitrators and happy to have this matter resolved,” Mochal said.

Casady wrote in an email to Financial Planning that he was “pleased that LPL Financial and I have been vindicated as a result of this process.” He declined to elaborate.

Bashaw, reached via email at his Houston practice, JebCo, declined to comment on the case. However, his attorney in the arbitration claim, David Cosgrove of the Cosgrove Law Group, discussed it with Financial Planning in further correspondence.

In his closing argument at the hearing, Cosgrove had said, “You can give $16 million just for defamation, just for the public humiliation and the fact that they blew Jeb Bashaw back 30 years into his career.” Cosgrove displayed family photos of Bashaw, his late wife Kim and his 28-year-old daughter Mason Clelland during his closing statement, accusing LPL of not caring about Bashaw’s family and clients.

TOP EXECUTIVES INVOLVED IN CASE

The litigation involved LPL executives including onetime executive vice president (and former FINRA executive director of enforcement) Jim Shorris, and Spencer Lewis, vice president of its special investigations unit.

Bashaw’s lawyer had also obtained a subpoena for Robert Moore, LPL’s president at the time and now CEO of Cetera Financial Group, but did not serve him because there was not enough time allotted in the hearings to call Moore, Cosgrove says — even though Moore’s name frequently came up as a home-office main point of contact for Bashaw.

In a September 2014 email to Shorris about the firm’s U5 filing on the termination, Moore called Bashaw’s exit “sad to see.”

Representatives for Moore at Cetera declined a request for comment, citing a company policy against discussing legal matters involving outside firms or individuals.

LPL’s largest 25 producers, Bashaw among them, had enjoyed close relationships with the CEO; top producers go on annual trips to luxury locales like Hawaii and Monaco, among others. Casady had traveled to Houston in 2011 for a party celebrating Bashaw’s 10 years with the firm, and LPL endowed a scholarship to Cristo Rey Jesuit, a high school in Houston, where Bashaw is very involved with the Catholic Church. (Casady is the son of an Episcopal minister, and he and his wife have a foundation that supports education.)

Yet Bashaw and Casady differ in their recollections of the vacation weekend on Cape Cod. Casady remembered conversations about their mutual “man crush” on the country singer Tim McGraw, as well as the engagement of Bashaw’s daughter. Cosgrove, Bashaw’s lawyer, suggested the two men talked about LPL’s problems with FINRA. Under questioning from Cosgrove, Casady said that as head of a publicly traded company he would not disclose such regulatory matters to Bashaw.

LPL said neither Casady nor Moore participated in the investigation of Bashaw or in the decision to fire him. Rather, the decision came from the compliance team, not any of LPL’s business divisions. Casady gave way to current CEO Dan Arnold in January 2017.

COMPLIANCE IN CONTEXT

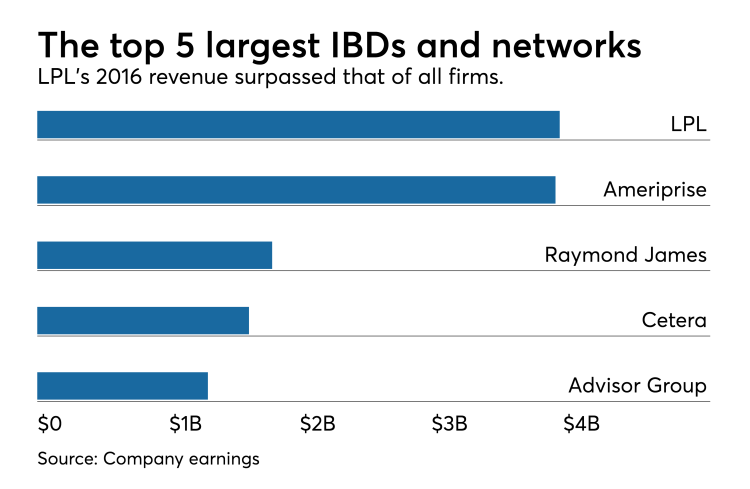

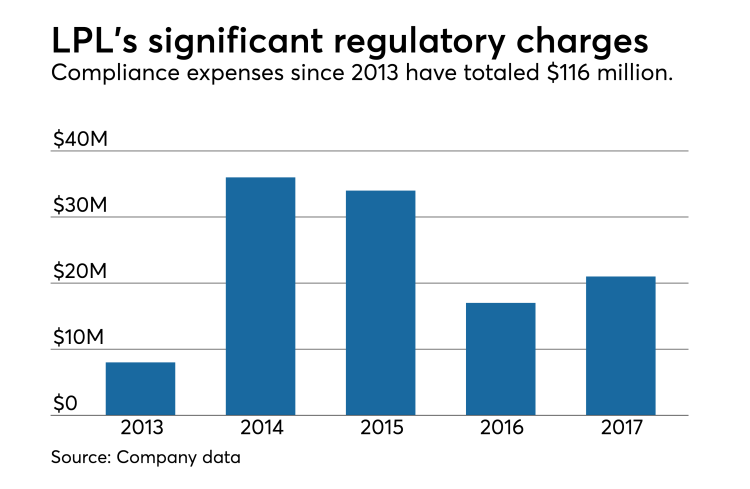

LPL has paid out $116 million in legal, regulatory and other compliance costs since 2013, a substantial amount for an IBD but less than such spending by wirehouse firms. While a sustained objection by LPL’s legal team prevented Bashaw and his lawyers from discussing past cases, they did cite an investigation by Texas securities regulators into LPL’s supervision of a broker, who was not publicly identified.

The Texas State Securities Board fined LPL $95,000 in February 2016, alleging that LPL failed to properly investigate a tip that one of its advisors had taken a loan from a client. The regulators required LPL to make major changes in its supervisory procedures.

According to the regulator’s consent order, an LPL investigator probing the tip failed to detect a $1 million loan from a client or another loan from the same client a year and half later. LPL’s investigators also hadn’t noticed that the surname of a Bashaw client was part of the name of the entity responsible for a deposit of $1 million in the unnamed broker’s account, the regulators said. The company fired the broker on Sept. 24, 2014 — the same date as Bashaw’s termination.

Spencer Lewis, now vice president of LPL’s investigation unit, testified that the case had been about Bashaw and that Bashaw’s brother-in-law Scott Pratt was the person who tipped off LPL in 2011. A spokesman for the Texas State Securities Board declined to comment.

Pratt, a former advisor at Bashaw’s practice, reported that Bashaw had borrowed from a Pratt family trust, according to Lewis. He noted that loans from family members are allowed under FINRA and LPL rules. (Like his sister, Pratt suffered from Huntington’s disease and died later in 2011, according to Bashaw.)

Lewis, who was part of the review prompted by the tip, said he did not believe Bashaw had been fully honest in discussing the $1 million loan. He acknowledged, however, that Bashaw had listed the Blackwell Enterprises Private Equity

Fund as a source of finance for the firm’s expansion. The late Houston businessman L.D. Blackwell provided the loans that led to Bashaw’s firing.

Asked by an LPL lawyer if Lewis wished that he had discovered the first loan by Blackwell during the 2011 probe, he answered, “Oh, absolutely.”

LPL formed its special investigations unit, which reviews serious misconduct by advisors, employees and vendors, around the time of Bashaw’s termination, according to Lewis. The firm hired as head of the unit a former FBI special agent and federal prosecutor named Scott Nussbum, in September 2014; Lewis reports to him.

Nussbum’s team has undertaken more than 160 internal investigations, leading to more than 40 terminations for “fraud, theft, and regulatory/policy violations,” according to his LinkedIn profile. Casady acknowledged in his testimony that LPL had found ample issues with its compliance.

“LPL during the time from 2012 through, you know, probably 2016, did an entire review of all of our systems for compliance, including email,” Casady said. The firm “replaced every single system” and doubled or tripled its compliance staff, he said, “all part of reviewing our risk management practices and rebuilding them.”

THE FIRING OF BASHAW

The investigation resulting in Bashaw’s termination began after a second whistleblower, another LPL advisor, alerted the firm to the two Blackwell loans in August 2014, LPL executives said in their testimony.

The firm accused Bashaw of undisclosed private securities transactions, the client loans and a business deal that posed a potential conflict of interest, according to FINRA BrokerCheck.

Blackwell’s estate won a $1.9 million settlement from LPL and Bashaw (it's unclear how payment of the settlement was divided) the day after Bashaw’s bankruptcy filing, his full CRD regulatory disclosure file shows.

Blackwell’s daughter Karen, a trustee and administrator of the estate, declined to comment. Bashaw listed her as his largest creditor in his bankruptcy, with a debt of $500,000 from a judgment amid total liabilities of $1 million to $10 million.

The other transactions at issue included investments by Blackwell in a members-only airline company, Texas Air Shuttle; an equity swap between JebCo and an asset manager, Ascendant Advisors; and purchases of shares in the energy investment fund Navitas Fund by another Bashaw client.

Bashaw’s lawyer argued that LPL should have known about the transactions from its oversight of his email and other means, including the 2011 review following the tip. Bashaw testified that Blackwell’s two loans provided capital to his firm rather than to him personally.

He also said that he quickly scrapped the Ascendant deal and received no compensation for the other ones. Pressed by LPL’s lawyers on the lack of private securities transactions disclosed in his annual compliance questionnaires,

Bashaw said he had not viewed his involvement with the transactions as formal participation.

He testified, for example, that he had simply introduced Blackwell to Texas Air Shuttle owner Ken Haney and told the client that Navitas appeared to be a good investment. LPL’s lawyers countered that even transactions bringing Bashaw no profit should have been disclosed.

Haney declined a request for an interview; Navitas manager John Lovoi and representatives for Ascendant didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In his May 2016 arbitration filing against LPL, Bashaw alleged defamation, negligent misrepresentation and an “an audit of Bashaw in furtherance of its plan to raid JebCo's employees, steal Bashaw's clients and to destroy his career.” Bashaw set his final request for damages at $16 million to $24 million.

The arbitrators’ rejected Bashaw’s claims in a 2-1 decision. One of the two arbitrators who ruled against him dissented on the panel’s decision to grant Bashaw a $25,000 payment from LPL over its failure to produce documents in the case.

THE PERSONAL TOLL

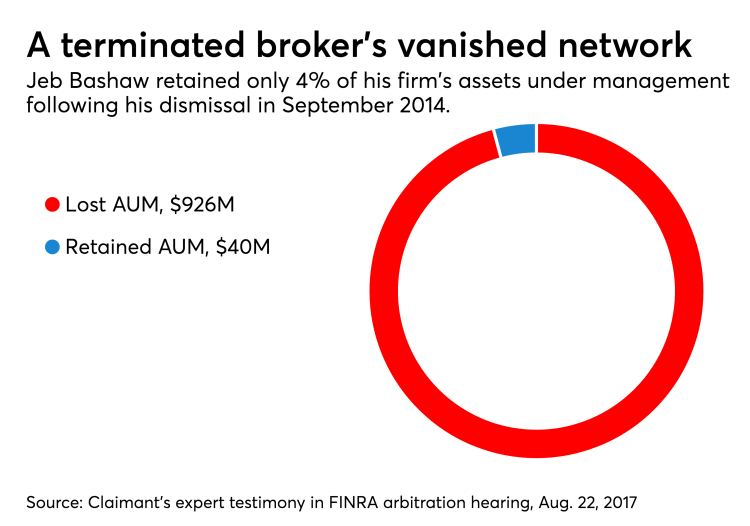

The sizable but unsuccessful request for damages spoke to how much JebCo’s business had expanded under LPL. Bashaw had received a buyout offer of $14 million for the firm in 2007, when it had about eight to 10 advisors with around $300 million in assets under management, he testified. Between 2007 and 2014, JebCo’s production nearly tripled to $9 million with more than 30 advisors across several offices, he said. He retained only 4% of its $966 million in AUM, roughly $40 million, after the termination, an accountant hired by the claimant said.

Bashaw’s daughter Mason and her then-fiancé, now husband, Lane Clelland, resigned from LPL, and the firm fired Bashaw’s assistant, Laura Thompson, and his compliance delegate, Tony Cilia. JebCo remains in business as an affiliated office of International Assets Advisory, with Mason Clelland one of its two other advisors.

In testimony during the arbitration, Clelland broke down as she testified that her father has “never been the same” since the termination and the April 2015 death of her mother.

The timing for the Bashaws was indeed dreadful. As Bashaw dealt with inquiries from the news media as well as FINRA and the Texas State Securities Board, he testified, his wife Kim’s condition reached its final stages. “We

were constantly battered by news reports, emails, clients calling, friends calling, the press calling. And we were under siege,” Bashaw said.

State regulators suspended his license for six months, and two FINRA lawyers and an investigator questioned him for 11 hours in March 2015 at the regulator’s Boston office, Bashaw testified, noting that the regulators have not handed down any major punishments against him.

FINRA spokeswoman Michelle Ong said she could not discuss Bashaw’s case. However, she noted that the regulator’s Central Review Group, a unit of its Office of Fraud Detection and Market Intelligence, reviews regulatory filings for potential misconduct, including U5 filings on terminations for cause.

Bashaw submitted a formal response to LPL’s U5 filing, contesting “the accuracy, validity and motive for the purported reasons for termination,” FINRA BrokerCheck shows.

THE PATRIOT ACT

The investigation by LPL compliance executives included obtaining Blackwell’s account information from Bank of America, according to the testimony by Lewis, Shorris and others. Section 314(b) of the Patriot Act allows firms to share such information if there is a suspicion of terrorism or money laundering. Yet Shorris answered “no” when asked by Bashaw’s lawyer whether there was a suggestion that Bashaw or Blackwell were involved in criminal activity.

LPL and BofA declined to answer any questions or provide further details about this request and compliance with it; their hands may be tied by federal confidentiality requirements.

Shorris said reviews of Bashaw’s emails about the loans and other transactions had provided LPL with most of the evidence. The investigative team wanted Blackwell’s bank records because they wanted to find out whether he had invested in Texas Air Shuttle, he said.

The law covers a very long list of suspected illegal conduct within anti-money laundering statutes, says Peter Hardy, the leader of the Ballard Spahr law firm’s AML team. Regulators also hold accountable firms that do not report suspicious activity, he notes.

“It’s not surprising to me that there was 314(b) sharing, because it’s pretty broad,” says Hardy, who emphasized that he isn’t familiar with the facts of Bashaw’s case. “There’s obviously always going to be a tension between the individual’s interests and the systemic interest behind combating money laundering. That’s one reason this is supposed to be confidential.”

A spokesman for the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, the division of the Treasury Department that institutions must notify if they share information under 314(b), said the agency cannot comment on individual cases. A spokesman for Bank of America said that it was unable to find anyone at the company familiar with the case and that it doesn’t comment on client matters.

THE COMMAND CENTER

When LPL’s investigation ramped up in late September 2014, Shorris, Lewis, Nussbum and Bill Morrissey, LPL’s managing director for business development, along with other staff members, set up a command center in a Houston hotel room, Lewis testified.

While Bashaw was out of town on a recruiting trip, on Sept. 24, Robert Prestininzi, LPL’s vice president of investigations, led a surprise visit to JebCo’s offices, according to testimony by Thompson, Bashaw’s assistant. Prestininzi questioned her for more than two hours, she said.

By her account, one member of his team played the good cop, telling her she was doing a good job and that she would be OK. The bad cop, Prestininzi, accused Bashaw of elder abuse in his handling of Blackwell and told her Casady and Moore had given her boss preferential treatment, Thompson said.

“He was cruel. He was rude. It was one of the most uncomfortable situations I’ve been in in my entire life,” she said. “That man was awful.”

Prestininzi’s group included a deputy from the Harris County Sheriff’s Office working off-duty as a private security guard whom Prestininzi identified to her as an auditor in training, Thompson testified. The deputy, John Klafka, testified that he had his loaded service weapon on his hip.

“I don’t remember her being upset,” Klafka said of the interview with Thompson, describing it as a roughly an hour long in which “everything was cordial.” Prestininzi testified that the conversation had been “professional” in tone even though Thompson had appeared nervous.

Bashaw’s daughter said Thompson was “shaken” by the interview.

Bashaw learned through calls to him by Thompson and other staff about the surprise visit to JebCo and immediately booked a flight to Houston from Jackson, Mississippi. Shorris reached him by phone shortly after he arrived at George

Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston, Bashaw testified.

Shorris and Thomas Estridge, a supervisory specialist, informed Bashaw of the firm’s investigation for the first time, according to Bashaw. They fired him in the course of a five-minute conversation, according to Estridge’s testimony. Shorris later said he no longer felt comfortable with Bashaw being registered with LPL.

Shorris had recommended Bashaw’s ouster to the executive leading the investigation, Ken Fasone, based on the type of conduct and its repetitive nature, he testified.

“As part of LPL’s annual advisor training and certification process, advisors — including branch managers, [office of supervisory jurisdiction] managers like Mr. Bashaw — are asked a series of questions about compliance with the firm’s rules and FINRA rules as well,” Shorris said. “He was asked questions that should have elicited — based on the information we found here — ‘yes’ answers. And he did not give those answers. So the information was incorrect.”

NO FURTHER RECOURSE?

Bashaw’s fight with LPL moved to federal court following the arbitration panel’s decision. In a motion to vacate the FINRA decision, Bashaw’s lawyers noted that LPL had been sanctioned over discovery in the case and alleged false testimony by a “key fact witness,” as well as misconduct and evident partiality by the arbitrators.

In late November, however, he filed to dismiss the motion, and U.S. District Judge Sim Lake confirmed the arbitration decision without any opposition from Bashaw on March 1. “We withdrew the motion because of the legal fees associated and the slim margin of success,” Bashaw’s lawyer in the proceeding, Ted Tredennick of Daniels & Tredennick, wrote in an email.

Bashaw’s bankruptcy case remains pending, with a hearing scheduled in May on his plan of reorganization.

In his closing statement in the arbitration, Cosgrove had accused LPL of not caring about Bashaw’s family and clients, and failing to detect and notify Bashaw of possible violations of its policies.

“That’s what supervision — that’s how it’s supposed to work,” Cosgrove said. “You’re not supposed to take money for something you’re not doing, then go back later and play

the gotcha game.”