“This time is different.”

That famous line, which mutual fund legend Sir John Templeton once called “among the four most costly words in the annals of investing,” is back in fashion these days when it comes to the Treasury yield curve. Skeptics from Goldman Sachs to Morgan Stanley Investment Management say the curve’s recessionary signals may be distorted now as a result of central bank policy that’s kept interest rates exceptionally low since the financial crisis.

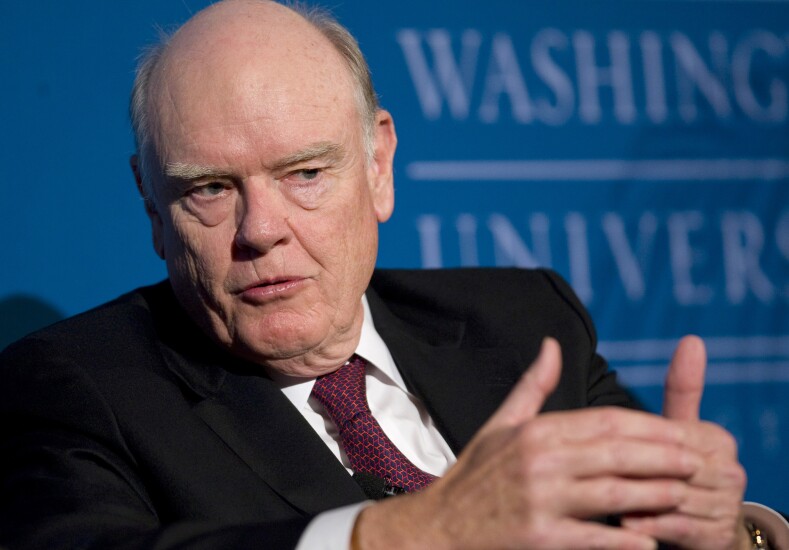

Is it deja vu all over again? More than a decade ago, then-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke dismissed the curve’s predictive powers after two of the most widely watched yield spreads inverted and then went flat. In Bernanke’s camp were then-Treasury Secretary John Snow and bond king Bill Gross. And we all now what happened next. That time was famously not different.

“People may say ‘this time is different’ due to quantitative easing, but this is a signal that’s been extremely strong,” said Charles Luke, whose team manages almost $21 billion in fixed-income assets for City National Rochdale in New York. “People who are not giving as much weight to it are missing the boat.”

The fact that yields on 10-year Treasurys are now back above those on three-month bills, after spending much of last week below, should not be mistaken as an all-clear signal. That type of “mini-inversion,” lasting one to eight days, can be a precursor to a longer-term episode, according to Luke, who has analyzed the history of inversions.

A flashback to what some policymakers and investors were saying in 2006 and 2007, after the 2-year/10-year and 3-month/10-year spreads had started to flash warnings, reveals some arguments that sound similar to today’s skepticism that inversions signal an upcoming recession.

Comments from policymakers and financial titans follow. — Bloomberg News