The coronavirus is likely to speed up the insolvency of the Social Security program, but that doesn’t mean it will fundamentally alter its outlook.

“What this crisis has shown once again is that we don't want to cut back on Social Security benefits,” says Alicia Munnell, director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. “It doesn't change the message very much in the sense that this is the most important program for Americans, and it should be financially secure.”

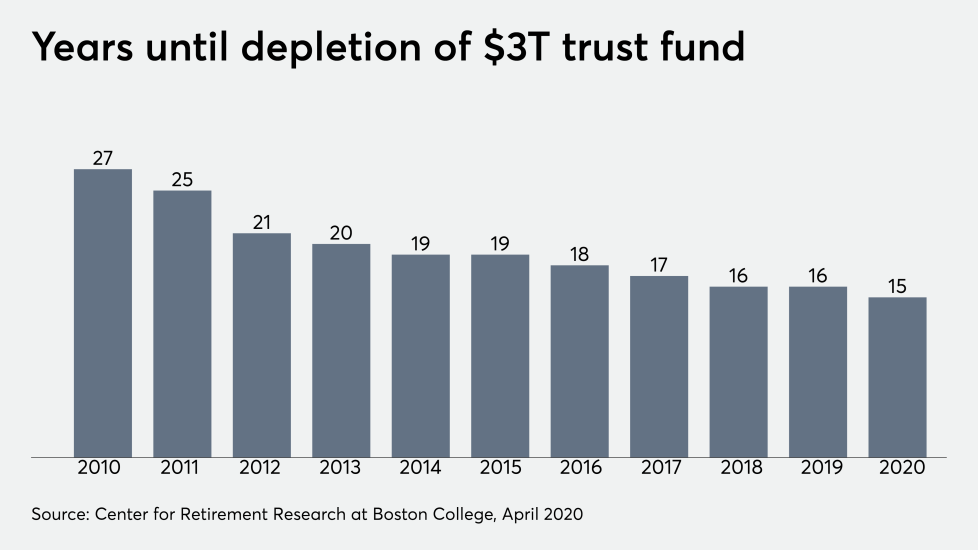

In 15 years, the roughly $3 trillion in the program’s trust fund will be depleted and payroll tax revenues will cover only 79% of legislated benefits, Munnell

The crisis could accelerate insolvency by reducing payroll tax revenue and pushing up disability claims, among other factors,

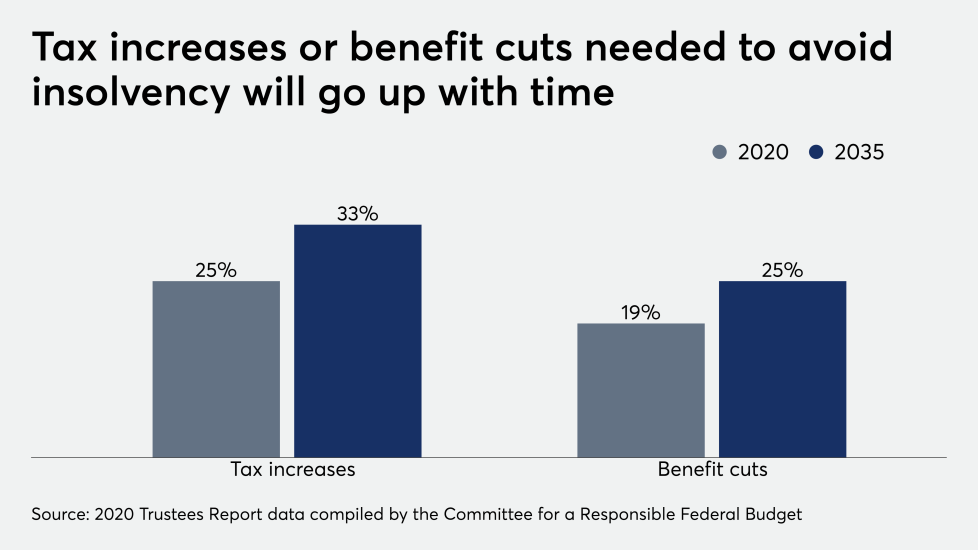

Yet Congressional action could avert cuts and fix the program’s long-term solvency. Increasing the cap on taxable wages, including health insurance benefits in the tax base or — in the most regressive solution — hiking the payroll tax by 1.6 percentage points on employees and employers would make Social Security solvent for the next 75 years, Munnell says.

Though the 75-year deficit projection rose in 2019, before the pandemic, finding revenue to make up the shortfall remains a “manageable exercise,” she says. Letting the issue linger for another decade or so would result in a benefits cut of about 25% in 15 years.

“Every time we have a catastrophe like this, Social Security demonstrates its worth,” Munnell says. “It's a stabilizing force, it's something that people can absolutely rely on.”

To see the latest figures on the program’s financial outlook, scroll down. For more on the 2020 trustees report and the potential impact of the coronavirus,