More than seven in 10 American investors see low-cost index funds as the best way to build long-term wealth,

Are they?

Over two decades, the asset management industry’s biggest players have preached a simple message to mainstream investors: Forget the high costs of traditional mutual funds, whose managers seek to nail superior returns through bespoke trading strategies. Instead, go in on cheaper, outperforming index funds run by a computer program that replicates the ups and downs of a benchmark, like the Standard & Poor’s 500 index of blue-chip U.S. companies. The pitch: Sitting back to “passively” mirror the ups and downs of an established formula bags you more money over the long haul.

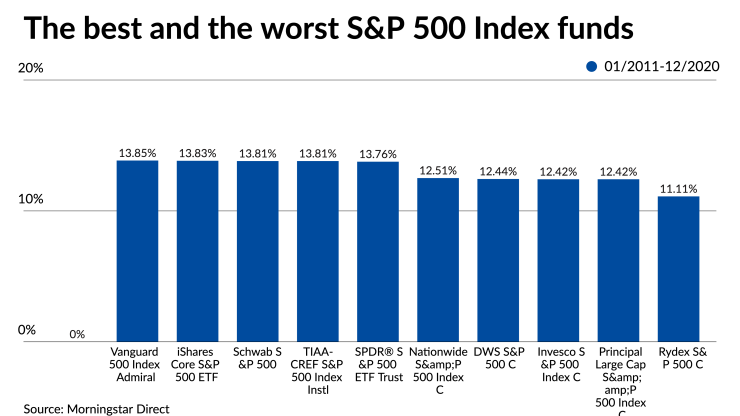

But the passive principle is not as clear cut as millions of investors and advisors think. Index funds come both as mutual funds and tax-efficient exchange-traded funds (ETFs are like a mutual fund but trade just like a stock). And their returns can vary widely.

New “closet activist” index funds pick winners and losers and hide their daily holdings, just like a mutual fund. Conversely, some high-cost mutual funds are indexers in disguise. Even the performance of plain-vanilla funds that track the same benchmark vary. Last October, the