In 2001, Vanguard, the world’s second-largest asset manager, acquired a

patent for a novel, tax-efficient fund structure that blends a mutual fund and an ETF by bolting on an ETF share class to its existing stock mutual funds. The patent expires in May 2023, which could open the flood gates to lookalike funds from competitors — and to greater scrutiny by regulators and critics, who argue that the structure’s tax benefits are controversial.

Vanguard’s secret sauce has several benefits.

Ordinarily, investors in a mutual fund owe capital gains taxes when that fund sells stock. The Vanguard patent uses an obscure, decades-old tax loophole to eliminate those levies both in a mutual fund and an ETF.

The loophole says that when withdrawals from a fund are paid with stock, not with cash, there’s no capital gains hit for the investor. For withdrawals, Vanguard uses rapid trades to whisk appreciated stock out of both a mutual fund and its sister ETF, then rapidly injects stock back in. A 2019 Bloomberg

investigation detailed how those so-called “heartbeat” trades are fueled by big banks.

Investors can swap their mutual fund shares for shares in a “

sister” ETF, all without owing taxes on the profits. The tax erasure not only reduces taxes on paper profits but also allows investors to defer paying taxes on their profits until they ultimately sell their mutual fund.

Because the patented structure involves two classes of shares, it gives investors the choice of holding a single investing strategy as a mutual fund or as an ETF. Vanguard’s secret method bolts an ETF onto an existing mutual fund, in contrast to competitors that issue stand-alone ETFs. While the entire investment holds the same securities, the ETF portion has a separate class of shares. The structure allows Vanguard “to have an ETF product that is almost identical to its mutual fund counterpart, which gives investors a wider range of product choice,” Shapiro said. “One fund, two share classes — that is unique.”

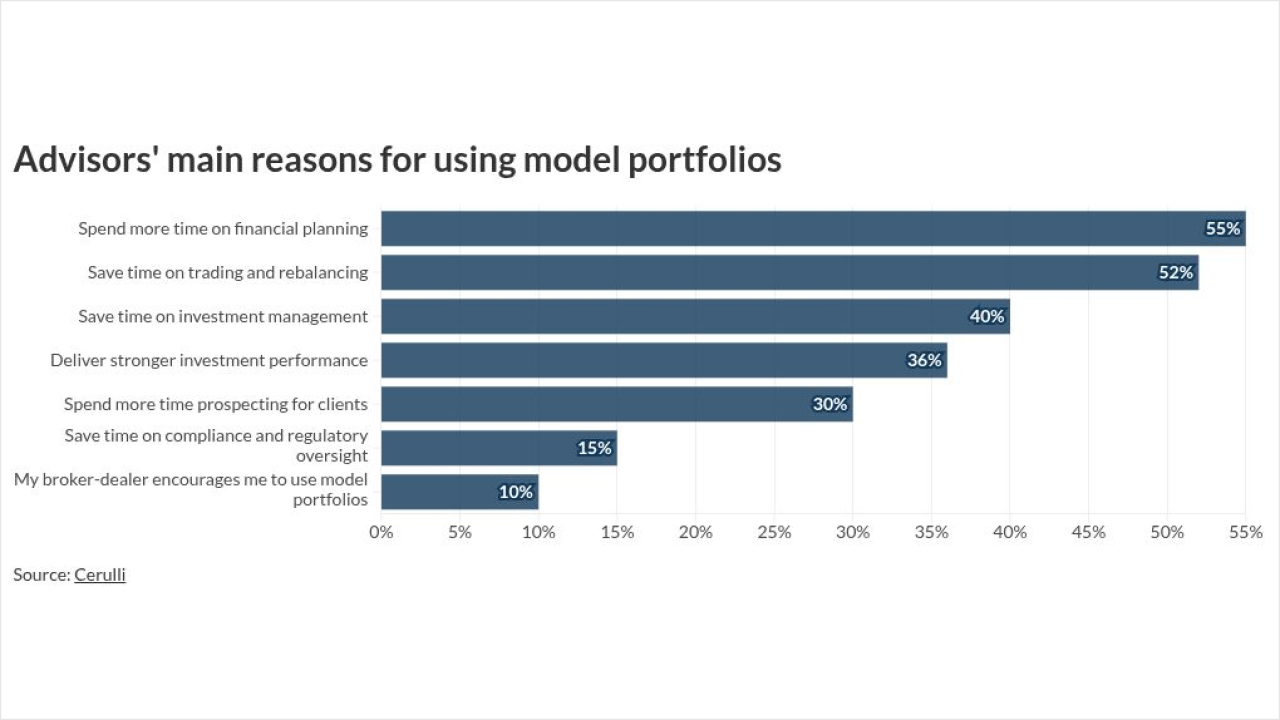

Prior Cerulli research cited in the firm’s

U.S. Exchange-Traded Fund Markets 2021 report showed that nearly four in 10, or 38%, of ETF issuers were considering adopting the Vanguard model once its patent expires. “Managers considering launching active ETFs should also keep an eye on the dual-share-class structure used by Vanguard, which comes off patent in 2023,” the Cerulli ETF report said.

The benefit to financial advisors is that they “wouldn’t have to dig into specific differences between what’s in the mutual fund and what’s in the ETF,” Shapiro said. Still, he added that “it’s an open question” whether the new breed of active ETFs will get a green light to use the Vanguard recipe, given the controversy over its tax benefits. “It’s not clear that the SEC would approve it,” he said.