Welcome back to "

Americans have a problem with estate planning: They know they should do it, but most don't. About seven out of 10 U.S. adults believe it's important to write a will, but only 26% have written one, according to the estate planning company

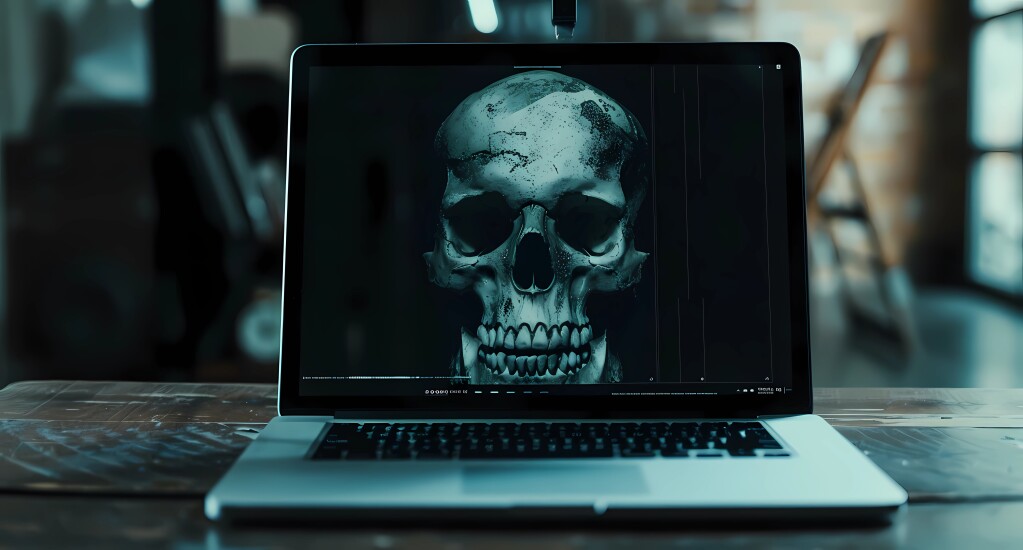

What could explain this disparity? One possible answer is that it's simply uncomfortable to contemplate one's own death, let alone plan for it in detail. But for a financial advisor to help with someone's estate planning — or even

This raises a tricky question: How do you talk to a client about death without spooking them? Planners have employed

READ MORE:

One wealth manager could use some of those ideas. Noah Damsky, CFA and founder of

Dear advisors,

How do you encourage clients to set up a trust for their children without freaking them out?

Alarmingly, I find many clients in their 60s and 70s don't have a trust when they first come to us. My intention is always to help clients prepare in advance for any adverse life events, but broaching the subject can feel like walking a tightrope.

We typically consider a revocable trust, to pass wealth down to the children after both parents die. Since the conversation is centered around death, it can get highly emotional. And for me, as a relatively young advisor, the age dynamic can be tricky.

I think there's always room to learn from others when it comes to handling difficult subjects like this. How would you approach it?

Sincerely,

Noah Damsky

And here's what financial advisors wrote back: